Abstract

Memory consolidation typically occurs slowly during periods of rest or sleep following memory encoding. However, under stressful conditions, memories may be rapidly consolidated. Given the long-standing lack of quantitative methods for neural activity during human memory consolidation, the mechanisms underlying rapid memory consolidation under stress remain unclear. This study proposes to employ computational neuroscience approaches to characterize in detail the neural replay process during human episodic memory consolidation under stress. Furthermore, we will integrate interdisciplinary methods including cognitive psychology, brain imaging techniques, machine learning, neuroendocrine regulation, stress induction, and physiological and biochemical detection to test the "double-edged sword" hypothesis of stress on neural replay: although stress may accelerate the speed of neural replay and promote memory consolidation, it may simultaneously reduce the accuracy of neural replay and disrupt its sequential order. This study will: (1) compare multidimensional feature differences in neural replay between stress and non-stress states; (2) explore the interactive effects between neural replay and memory retrieval and encoding under stress; (3) attempt to regulate human stress responses using neuroendocrine and environmental strategies, thereby influencing neural replay. This research can help identify ideal brain states that promote memory consolidation and integrate neural replay studies across humans and animals. Simultaneously, this study may also provide novel strategies for protecting episodic memory function under stress and for intervening in memory impairments in stress-related psychiatric disorders.

Full Text

Preamble

The Neural Replay Mechanisms of Episodic Memory Consolidation Under Stress in Humans

LIU Wei¹,², CHEN Ruixin¹,², GUO JinPeng¹,²

¹ Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior (CCNU), Ministry of Education, Wuhan, China

² Key Laboratory of Human Development and Mental Health of Hubei Province, School of Psychology, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China

Abstract

Memory consolidation typically occurs slowly during rest or sleep periods following memory encoding. Under stress, however, memory consolidation may accelerate considerably. The mechanisms underlying this rapid consolidation in stressful circumstances remain unclear, primarily due to the longstanding absence of quantitative methodologies for investigating neural activity during human memory consolidation. This research aims to employ computational neuroscience techniques to meticulously characterize neural replay during the consolidation of episodic memory under stress. Specifically, we propose an integrated approach involving cognitive psychology, neuroimaging, machine learning, neuroendocrine regulation, stress induction, and physiological and biochemical assessments to examine the "double-edged sword" hypothesis related to stress and neural replay. Although stress might hasten the rate of neural replay, thereby facilitating memory consolidation, it could simultaneously compromise the accuracy of neural replay and disrupt its sequentiality. Our study will: (1) juxtapose the multi-dimensional characteristics of neural replay under stress and non-stress conditions; (2) probe the interplay between neural replay and memory retrieval and encoding in stressful conditions; and (3) strive to employ neuroendocrine and environmental tactics to modulate human stress responses, which in turn could influence neural replay during consolidation. The implications of this research are twofold: it could help identify the optimal brain state to enhance memory consolidation and bridge the gap between human and animal studies on neural replay. At the same time, it could illuminate new strategies for preserving episodic memory function under stress and intervening in memory deficits seen in stress-associated psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: memory consolidation; memory retrieval; acute stress; neural replay; episodic memory

1. Problem Statement

In modern society, overwhelming stress and mental pressure have quietly become significant factors threatening the quality of life and mental health of Chinese citizens. Scientific research indicates that stress not only impairs cognitive function in the short term but may also transform into chronic pressure, becoming a key risk factor for a range of psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (de Kloet et al., 2005). Therefore, strengthening stress-related scientific research, deeply exploring its potential negative impacts and underlying mechanisms, and developing effective regulatory approaches represent an important scientific innovation priority oriented toward public health and well-being.

Mental pressure (or stress in the broad sense) encompasses both acute stress and chronic stress. Unmitigated acute stress has a certain probability of converting into chronic stress. In this study, "stress" refers specifically to acute stress, emphasizing physiological-psychological reactions within a particular time window, such as various highly threatening emergencies that cause intense mental tension. These range from sudden injuries, accidents, important examinations, school admissions, and job interviews to personally experiencing or witnessing serious accidents or natural disasters like the MH370 disappearance, the May 12 Wenchuan earthquake, or the September 11 plane crashes. From an experimental/physiological psychology perspective, acute stress has clear physiological indicators and can be induced in the laboratory under procedures compliant with human experimental ethics, making it suitable for neuroimaging research.

How stress affects memory constitutes a core question in stress research (Schwabe et al., 2022). As early as the scientifically underdeveloped Middle Ages, people already had intuitive understanding of the relationship between stress and memory. Some medieval tribal communities practiced a custom where, after children participated in historically significant ceremonies, they would immediately be thrown into water so that the adults believed this would leave lifelong, unforgettable memories of the ceremony in the children's minds (McGaugh, 2003).

This folk custom demonstrates that people have long recognized the potential role of stress in promoting memory consolidation and forming durable memory traces. To date, our understanding of memory consolidation mechanisms has primarily derived from molecular neuroscience research in animal models (Ambrose et al., 2016; Carr et al., 2011; Karlsson & Frank, 2009). Although animal studies can deeply dissect the neural circuits underlying memory consolidation, they are limited by the types of memory tasks animals can perform, making it difficult to correlate consolidation-period neural activities with specific memory performance. Human non-invasive neuroimaging has attempted to explain the association between consolidation-period neural activity and subsequent memory performance, but due to the long-term lack of precise quantification methods for consolidation-period neural activity, such research has often been limited to coarse descriptions using brain activity intensity, patterns, and functional connectivity, without characterizing the dynamic neural processes of memory replay during consolidation (Tambini et al., 2010; Tambini & Davachi, 2013, 2019). However, recent years have witnessed the integration of high-temporal-resolution non-invasive brain imaging with machine learning and computational modeling, making it possible to describe human neural replay during memory consolidation (Y. Liu et al., 2019; Y. Liu, Dolan, et al., 2021; Schuck & Niv, 2019a; Wittkuhn & Schuck, 2021). Previous studies have focused on neural replay under normal conditions and examined its relationship with higher-order intelligence such as decision-making (Kurth-Nelson et al., 2023; Y. Liu, Mattar, et al., 2021), leaving the scientific question of how stress affects human neural replay during memory consolidation largely unexplored. Through literature review, we have summarized previous studies on stress effects on memory consolidation and compiled them into Table 1. As shown in Table 1, without considering memory accuracy and sequentiality, most previous studies found that stress enhances memory consolidation. No study has yet probed the double-edged sword effect of stress on memory consolidation using multiple memory retrieval paradigms.

This research aims to integrate interdisciplinary methods including cognitive psychology, brain imaging, machine learning, computational modeling, neuroendocrine regulation, and physiological-biochemical detection of stress to reveal the cognitive neural mechanisms of rapid memory consolidation under stress using computational neuroscience approaches. We will also examine how neural replay features under stress relate to memory retrieval and encoding and how they are modulated by neuroendocrine and environmental factors. This study holds theoretical significance for seeking the optimal brain state for memory consolidation and integrating human and animal research on stress and neural replay. Practically, it can also provide references and guidance for protecting memory function under stress and understanding and intervening in memory impairments in stress-related psychiatric disorders.

2. Research Status and Developmental Trends

2.1 Psychophysiological Effects of Stress and Their Impact on Memory Function

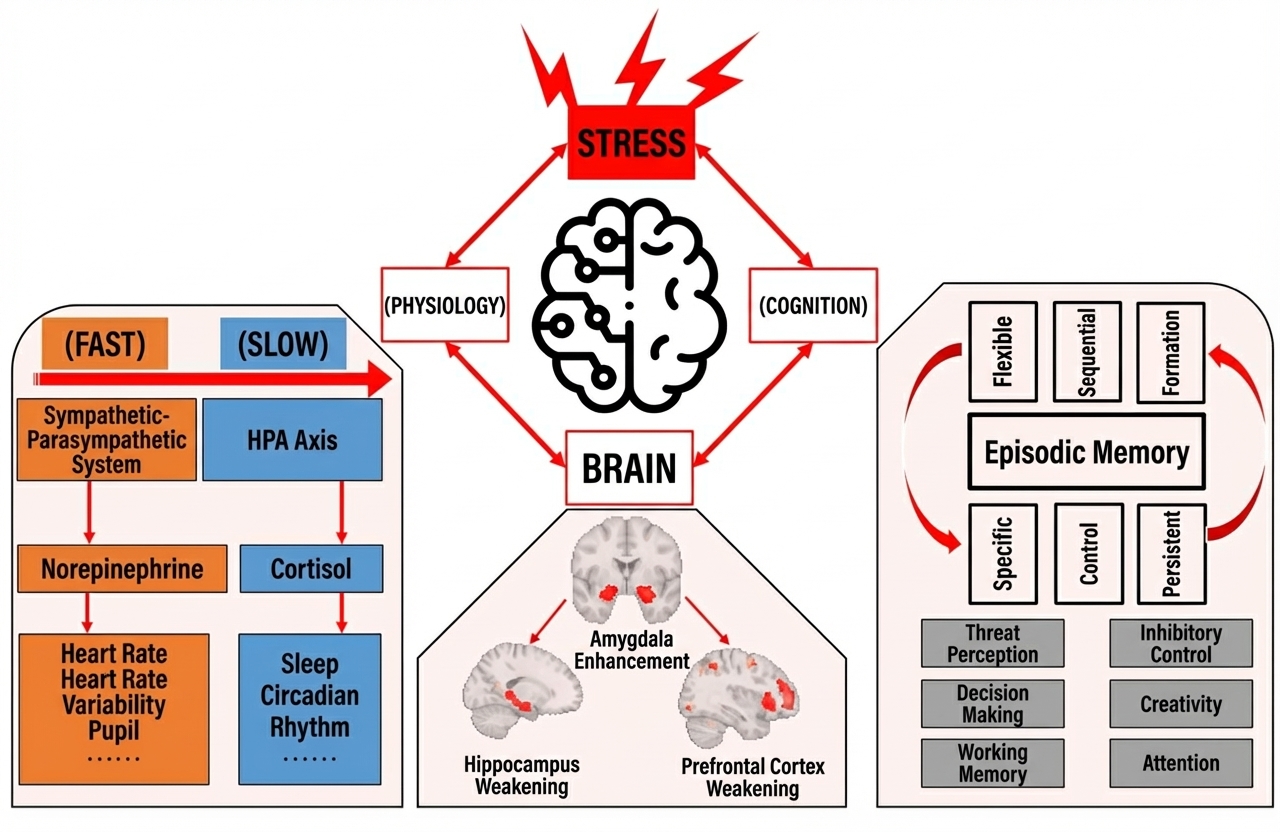

Stress is a double-edged sword: on one hand, it enables rapid detection of danger and prepares us for future challenges; on the other hand, it makes it difficult to concentrate attention and make rational decisions in complex environments (de Kloet et al., 2005). Stress triggers complex neuroendocrine-brain-cognitive changes (Figure 1). While neuroendocrine responses to stress can be quantified in animal models (Armario et al., 2008; Rao et al., 2012; Yuen et al., 2009), ethical and technical limitations prevent real-time description of dynamic neuroendocrine changes in the human brain. In contrast, human stress research has primarily focused on using non-invasive brain imaging techniques (such as fMRI, EEG, and MEG) to explore associations between altered neural activity under stress and cognitive function. For instance, domestic scholars have investigated changes in working memory and attention to threat stimuli (Luo et al., 2018), creativity (Duan et al., 2019, 2020), and inhibitory control under stress (Chang et al., 2020; Chang & Yu, 2019).

This study focuses on how stress affects human memory consolidation. Previous research has found that stress impacts different memory stages (encoding, consolidation, and retrieval) differently. Specifically, stress effects on memory encoding vary depending on the valence of memory material: stress enhances encoding of emotional information while weakening encoding of neutral information (Buchanan & Lovallo, 2001). The relationship between stress and memory retrieval appears more direct (i.e., stress impairs memory retrieval), with relatively clear underlying mechanisms (Gagnon et al., 2019; Wolf, 2017). The relationship between stress and memory consolidation has been studied but lacks a simple conclusion: while stress is generally believed to enhance consolidation, some studies have found an inverted U-shaped curve, where moderate stress enhances consolidation while excessive stress impairs it (Cahill et al., 2003; McCullough et al., 2015).

Human non-invasive neuroimaging has revealed how stress influences memory encoding and retrieval by modulating the hippocampus-prefrontal cortex-amygdala circuit. (A) Glucocorticoids secreted during stress primarily act on the hippocampus, one of the brain regions most critical for memory. In both rodent and human studies, researchers have indeed found that elevated glucocorticoid levels during stress are associated with impaired hippocampus-related memory retrieval performance (de Quervain et al., 1998; Lindauer et al., 2006; Newcomer et al., 1999; Roozendaal et al., 2006). Human fMRI experiments directly comparing memory-related neural activity under stress and non-stress conditions have found that stress reduces hippocampal activation during memory retrieval (Gagnon et al., 2019). (B) Additionally, stress-induced memory impairment may also be related to prefrontal cortex dysfunction (Arnsten, 2009). For example, research shows that stress reduces dorsolateral prefrontal neural activity intensity (Qin et al., 2009) and neural oscillations during working memory (Gärtner et al., 2014). Pharmacologically induced glucocorticoid secretion (the primary physiological-biochemical response triggered by stress) impairs prefrontal activity intensity during memory retrieval tasks (Oei et al., 2007). (C) Professor Guillén Fernández's team at the Donders Institute for Brain Research in the Netherlands has used non-invasive neuroimaging to explore amygdala activity characteristics under stress. Overall, stress enhances amygdala responses to emotional faces (van Marle et al., 2009), but the degree of enhancement is modulated by individual genetic phenotypes (Cousijn et al., 2010). Enhanced amygdala neural activity under emotional stress forms the basis for its influence on memory processes (Cahill et al., 1995, 1996; Dolcos et al., 2004; LaBar & Cabeza, 2006). Direct brain stimulation studies in humans have found that electrical stimulation of the amygdala can enhance episodic memory encoding (Inman et al., 2018). Therefore, stress-induced enhancement of amygdala activity will have profound effects on memory function. Notably, most previous research on stress-memory interactions has observed hippocampus-amygdala-prefrontal activity characteristics separately, with only a few studies taking a large-scale brain network perspective. The Guillén Fernández team integrated psychological experimental paradigms, non-invasive neuroimaging, neuroendocrine manipulation, physiological-biochemical detection, and pupillometry to reveal how stress affects large-scale human brain networks, with results published in Science (Hermans et al., 2011). This study found that stress alters the dynamic balance and resource allocation between brain networks, exhibiting a "double-edged sword" effect: stress concentrates cognitive resources on the salience network (also called the emotional stress network) centered on the amygdala, making individuals sensitive to fear and vigilance stimuli, while simultaneously reducing resources available to the executive control network centered on the prefrontal cortex, thereby impairing performance on high cognitive load tasks such as memory and decision-making. Based on this, the team proposed a large-scale brain network dynamic adaptation model for human stress response (Hermans et al., 2014), which has exerted broad influence on subsequent human stress neuroimaging research.

Despite these advances, our understanding of how stress affects memory consolidation remains limited, possibly because memory encoding and retrieval research better fits standard cognitive neuroscience paradigms. Such studies typically reveal the neural basis of successful memory processes by correlating recorded neural signals with successful versus failed memory encoding or retrieval events (Fernández et al., 1999; Frankland et al., 2019; W. Liu et al., 2022). However, the challenge in memory consolidation research lies in the need for precise quantification of cognitive information contained in spontaneous neural activity (Fox & Raichle, 2007). Although we can record neural activity during memory consolidation, it is difficult to directly know the underlying cognitive processes behind this activity and their onset and offset times. Therefore, to understand memory consolidation under stress, we must first identify quantifiable neural metrics to describe the dynamic neural processes during consolidation.

2.2 Neural Replay as the Neural Basis of Memory Consolidation

Scientists have long searched for the neural basis of memory consolidation and have established a considerable understanding framework (Squire et al., 2015). Memory consolidation can occur both during wakefulness (awake consolidation) and during sleep (sleep consolidation) (Klinzing et al., 2019; Wamsley, 2022). Two important concepts related to memory consolidation are memory reactivation and memory replay. Memory reactivation refers to the re-emergence of neural patterns similar to those during perception when a specific (single) memory is evoked. Memory replay emphasizes that multiple memory traces are reactivated in the brain in a certain sequence. Neural replay is considered the underlying neural mechanism of memory replay, and this project focuses on neural replay processes during wakefulness.

As the neural basis of memory consolidation, neural replay must satisfy three characteristics: (1) In the absence of external sensory input, neural representations corresponding to memories repeatedly appear; (2) It occurs post-encoding and can persist for some time; (3) It coordinates with neural activity in widespread cortical regions, transferring memory representations that originally depend on the hippocampus to extensive cortical areas (Carr et al., 2011). The phenomenon of spatial memory replay during subsequent wakefulness or sleep discovered in rodents satisfies all these features (Davidson et al., 2009; Foster & Wilson, 2006; Ji & Wilson, 2007). Due to technical limitations, human neural replay research relies on indirect methods, such as inferring the neural basis of memory consolidation by comparing neural activity during memory retrieval before and after consolidation (Takashima et al., 2006, 2009). However, with the development of human resting-state fMRI technology, direct investigation of human memory consolidation has become possible (Guerra-Carrillo et al., 2014). Tambini and Davachi's research team used pairwise multi-voxel correlation analysis and inter-region functional connectivity methods to compare neural activity patterns during memory encoding and consolidation, finding that local and global activity patterns centered on the hippocampus during consolidation closely resembled those during encoding, differing from the pure rest period before task onset (Tambini et al., 2010; Tambini & Davachi, 2013, 2019). However, considering the temporal characteristics of memory replay and the temporal resolution of fMRI, it is generally believed that the memory consolidation process observed with fMRI is more likely the superimposed result of multiple memory information reactivations. Nevertheless, some studies have reported that using functional MRI neural decoding can also detect sequential information in neural replay (Schuck & Niv, 2019b; Wittkuhn & Schuck, 2021). In summary, human fMRI-based neural replay research has extended animal neural replay studies in memory types, confirming that not only spatial information but also non-spatial abstract memory information can be replayed during human consolidation. Liu Yunzhe and colleagues used machine learning and computational modeling on MEG data to precisely quantify neural replay processes contained in spontaneous neural activity during rest. With the millisecond-level temporal resolution of MEG and advances in regression factor control and permutation-based statistical approaches, neuroscientists can quantify the timing and specific sequence of different memory information during consolidation, thereby achieving multi-dimensional precise characterization of human neural replay in mathematical terms (Y. Liu, Dolan, et al., 2021; Y. Liu et al., 2019; Y. Liu, Mattar, et al., 2021; Nour et al., 2021).

A critical step in establishing neural replay as the neural basis of memory consolidation is linking consolidation-period neural activity to subsequent memory retrieval performance. Animal studies have found that the intensity of awake neural replay can predict subsequent memory performance (Dupret et al., 2010), and human resting-state functional connectivity studies have also found that hippocampal functional connectivity patterns during consolidation can predict individual differences in associative memory (Tambini et al., 2010; Tambini & Davachi, 2013). However, the associative memory paradigm is not an ideal measurement for neural replay behavior management because it only reflects local features of neural replay. For example, neural replay emphasizes the sequential order of multiple pieces of information, yet no human memory consolidation study has incorporated memory sequence property measurements in the subsequent memory retrieval phase. Therefore, despite new quantification methods for human neural replay, we still know little about the relationship between different features of neural replay and different characteristics of episodic memory (such as persistence, specificity, and sequentiality). To address this, we need to design different memory task paradigms after consolidation to measure different aspects of memory performance.

2.3 Seeking the Optimal Brain State for Memory Consolidation

The aforementioned research has confirmed that non-invasive brain imaging can capture neural replay in the human brain, so we can seek the optimal brain state for memory consolidation by observing changes in neural replay. Previous studies have primarily focused on how memory material characteristics affect reactivation during consolidation, such as reward (Murayama & Kitagami, 2014; Murayama & Kuhbandner, 2011), emotional valence (Sharot & Phelps, 2004), relationship with future behavior (Wilhelm et al., 2011), and association with prior knowledge (Tse et al., 2007; van Kesteren et al., 2010). No study has yet explored what characteristics consolidated memories exhibit during the consolidation period. Traditional system consolidation theory posits that after memory formation, a slow and natural consolidation process occurs over time, with memory representations shifting from the hippocampus to widespread cortical regions (Frankland & Bontempi, 2005). However, recent research has found that enhancing encoding efficiency through retrieval practice can produce a "fast" memory consolidation effect (Fast Consolidation Hypothesis) (Antony et al., 2017). Researchers using multivariate pattern analysis techniques (Cohen et al., 2017) have preliminarily confirmed that the memory enhancement effect of retrieval practice is related to rapid memory consolidation (Ferreira et al., 2019; W. Liu et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2020; Zhuang et al., 2021). From a neural mechanism perspective, retrieval practice enhances representational distinctiveness in the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and visual cortex.

In addition to memory characteristics themselves, the brain's global state also influences neural replay during consolidation. Both animal models and human memory decoding studies have found abnormal neural replay in schizophrenia (Nour et al., 2021; Suh et al., 2013). Considering that hallucinations and delusions are core symptoms of schizophrenia (McCutcheon et al., 2020), we can speculate that abnormal neural replay may be the neural mechanism underlying hallucinations and delusions. Beyond pathological brain states, due to the continuity of brain states, the brain state prior to memory consolidation systematically influences neural activity during consolidation. Evidence for brain state continuity exists in memory encoding and retrieval domains: Tambini et al. found that brain states triggered by prior emotional memory encoding persisted into subsequent neutral memory encoding, accompanied by sustained brain activity and functional connectivity patterns corresponding to emotional stimuli, which enhanced neutral memory encoding (Tambini et al., 2017). Memory control after memory retrieval is more difficult because the brain network adapted for memory retrieval needs rapid reconfiguration to meet the demands of subsequent memory control tasks. If rapid reconfiguration fails and the brain state from memory retrieval persists into memory control, memory control faces failure risk (W. Liu, Kohn, et al., 2021). Similarly, we speculate that inducing stress in participants before memory consolidation will affect the subsequent consolidation process.

In animal models, scientists have found that using electric shocks or drugs to induce stress responses can enhance memory consolidation (Zinkin & Miller, 1967). Since then, a series of studies have revealed the neuroendocrine mechanisms through which stress hormones enhance memory consolidation (McGaugh, 2018), specifically the interaction between rapid noradrenergic responses and slow glucocorticoid responses following stress (Roozendaal et al., 2006). However, these neuroendocrine changes do not directly affect cognitive function but exert indirect effects by influencing neural activity in corresponding brain regions. Currently, no human study has used non-invasive brain imaging to reveal dynamic changes in memory consolidation under stress. Based on the aforementioned "double-edged sword" effect of stress on large-scale networks (Hermans et al., 2014), we hypothesize that stress also has a "double-edged sword effect" on neural replay during consolidation, meaning that stress does not simply enhance memory consolidation but simultaneously enhances and impairs different features of neural replay (although stress may accelerate neural replay speed, it reduces the accuracy of memory representations during replay and disrupts the sequence of neural replay).

2.4 Modulation Methods for Neural Replay and Their Neural Mechanisms

In animal models, neural replay can be precisely modulated through optogenetics (Deisseroth, 2011): by establishing a real-time neural replay monitoring system, scientists can extend or shorten the duration of neural replay during the consolidation period in rodents and affect subsequent memory retrieval performance (Ego-Stengel & Wilson, 2009; Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2019). In human research, one possible method is targeted memory reactivation (TMR), which presents participants with sensory stimuli (such as sounds or odors) paired with encoded information during consolidation (usually during sleep) to reactivate encoded memories and observe corresponding cognitive and brain changes (Hu et al., 2020; Rasch et al., 2007). However, whether TMR effectively modulates neural replay remains controversial: first, some argue that presenting specific sensory stimuli during consolidation actually triggers memory retrieval processes, thereby disrupting the spontaneity of consolidation. Second, TMR typically can only reactivate single pieces of information, whereas neural replay emphasizes the dynamic reactivation of multiple memory information. Whether TMR can induce replay of a series of memories remains to be studied. Another possible modulation method for memory consolidation is non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). Tambini et al. used non-invasive brain stimulation to modulate memory consolidation: stimulating the visual cortex during consolidation could hinder memory reactivation and hippocampal-cortical interaction, with memory behavioral performance declining in retrieval tasks (Tambini & D'Esposito, 2020). However, human non-invasive brain stimulation can only stimulate a single cortical region and cannot reach the deep hippocampal structure, thus it should be considered as having indirect effects on neural replay. In summary, existing human neural replay modulation methods can only affect memory consolidation at the level of single stimulation or single brain region, still far from ideal modulation methods for memory consolidation. Since neural replay is difficult to precisely modulate in humans, perhaps we can indirectly modulate neural replay under stress by modulating stress responses. Previous studies have attempted to modulate human memory function under stress from two pathways: neuroendocrine and brain science. From a neuroendocrine perspective, the impairing effect of stress on memory retrieval disappears in healthy participants after taking propranolol (a non-selective β-receptor blocker, also known as Inderal) (de Quervain et al., 2007; Schwabe et al., 2009), while the enhancing effect of emotional arousal on memory encoding disappears (Cahill et al., 1994). From a brain science perspective, researchers have achieved good results in modulating working memory under stress by stimulating specific brain regions (such as dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) (Bogdanov & Schwabe, 2016). Environmental neuroscience is an emerging approach for stress modulation. Environmental neuroscience has found that human stress is largely influenced by living environments and has begun to reveal its neural mechanisms (Berman et al., 2019; F. Liu et al., 2023; Tost et al., 2015). One important influencing factor is urbanization: the team of Yu Chunshui at Tianjin Medical University found that regional urbanization levels have significant effects on brain structure and cognitive function in young populations (Xu et al., 2021). Stress neuroimaging research has also found that people living in cities show stronger amygdala activity when facing social stress (Lederbogen et al., 2011). Urbanization can affect human stress and brain through multiple factors, one relatively clear mechanism being that urbanization leads to reduced green environments, which can serve as protective factors against stress (Berto, 2014). Big data analysis during the COVID-19 pandemic found that people who had more contact with green environments during the pandemic could better maintain mental health (Lee et al., 2023). The Kühn team at the Max Planck Institute in Germany found through intervention studies that one hour of natural green environment exposure, compared to urban environment exposure, can effectively enhance human stress resistance, reducing amygdala activity when facing stress (Sudimac et al., 2022). Although research on using green environments to combat stress is still in its infancy, it has unique advantages: compared to neuroendocrine or brain stimulation research, green environment contact is not only low-cost and applicable in wide scenarios but can also be safely applied to children, adolescents, and elderly populations. Theoretical speculation suggests that the stress-resistance effect of green environments should differ from drugs or brain stimulation, but this lacks experimental verification. This study plans to use natural environment strategies as an emerging approach to modulate neural replay under stress by reducing stress responses. Natural environment contact can serve not only as an experimental manipulation method for externally regulating stress responses but also enable further comparison of the efficiency and mechanistic differences between environmental and neuroendocrine regulation.

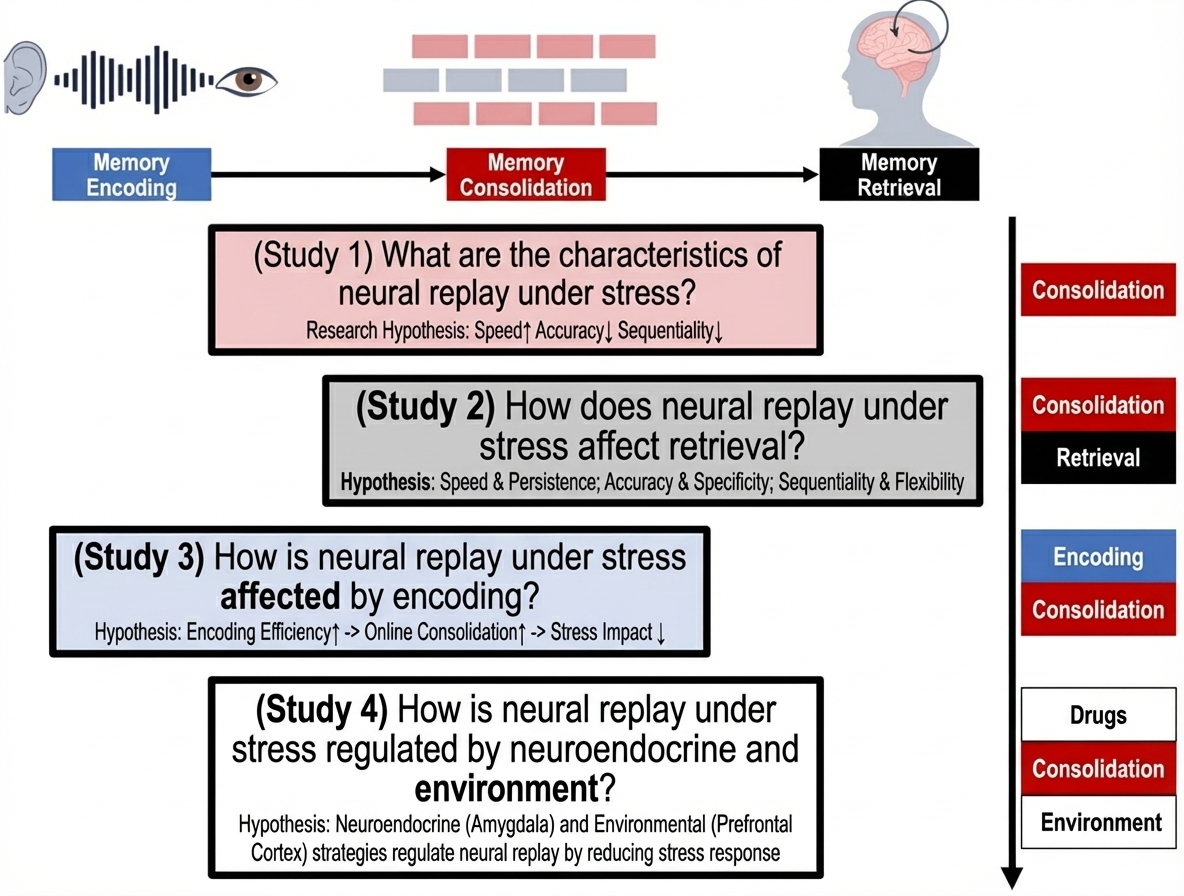

3. Research Proposal

This study proposes to reveal the neural replay mechanisms of rapid memory consolidation under stress through four studies (Figure 2). Study 1 will examine how stress states affect neural replay phenomena during memory consolidation. Study 2 will simultaneously focus on consolidation and retrieval periods, exploring how stress-induced neural replay abnormalities affect subsequent memory retrieval. Study 3 will simultaneously examine encoding and consolidation periods, investigating how memory encoding efficiency affects neural replay under stress. Based on the neural mechanisms revealed in Studies 1-3, Study 4 will introduce external modulation strategies (neuroendocrine and environmental) to regulate neural replay under stress by reducing individual stress responses.

Figure 2. Research Framework

3.1 Study 1: How Does Stress Affect Neural Replay Features During Memory Consolidation?

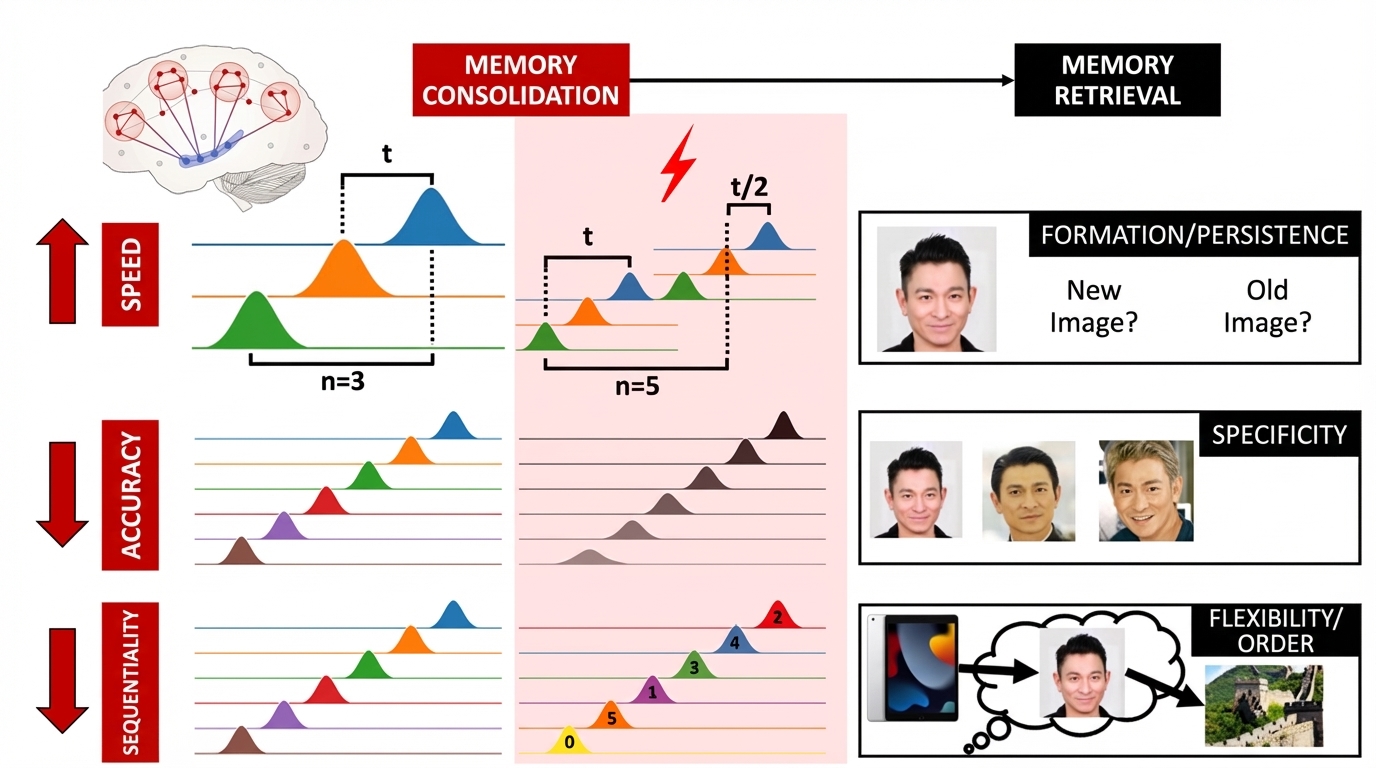

Study 1 aims to investigate how stress affects neural replay features during memory consolidation. Using a single-factor (stress/non-stress) within-subjects design, we will recruit healthy university students for EEG experiments under stress and non-stress conditions. The experiment主要包括 three main phases: memory encoding-testing, stress induction, and neural replay capture. Specifically, participants will learn picture sequences during the memory encoding phase and immediately undergo memory testing to assess learning effectiveness. The Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) and math calculation tasks will be used to induce stress. Saliva samples will be collected five times throughout the experiment (before the experiment, after baseline memory testing, after stress induction, mid-EEG recording, and end of EEG recording) for cortisol quantification to confirm stress induction effectiveness and state maintenance duration. Immediately after stress induction, EEG will record participants' neural activity during the 5-minute memory consolidation period. Building on existing computational neuroscience methods that can quantify neural replay during consolidation (Y. Liu et al., 2019; Y. Liu, Dolan, et al., 2021), this study will quantify neural replay speed, accuracy, and sequentiality, and compare differences between stress and non-stress conditions. The key hypothesis is that although stress accelerates neural replay speed, it reduces the accuracy of memory representations during replay and disrupts neural replay sequence. This means that while stress can promote rapid information replay in the brain, this speed may come at the cost of memory quality, leading to decreased precision and organization of memory representations.

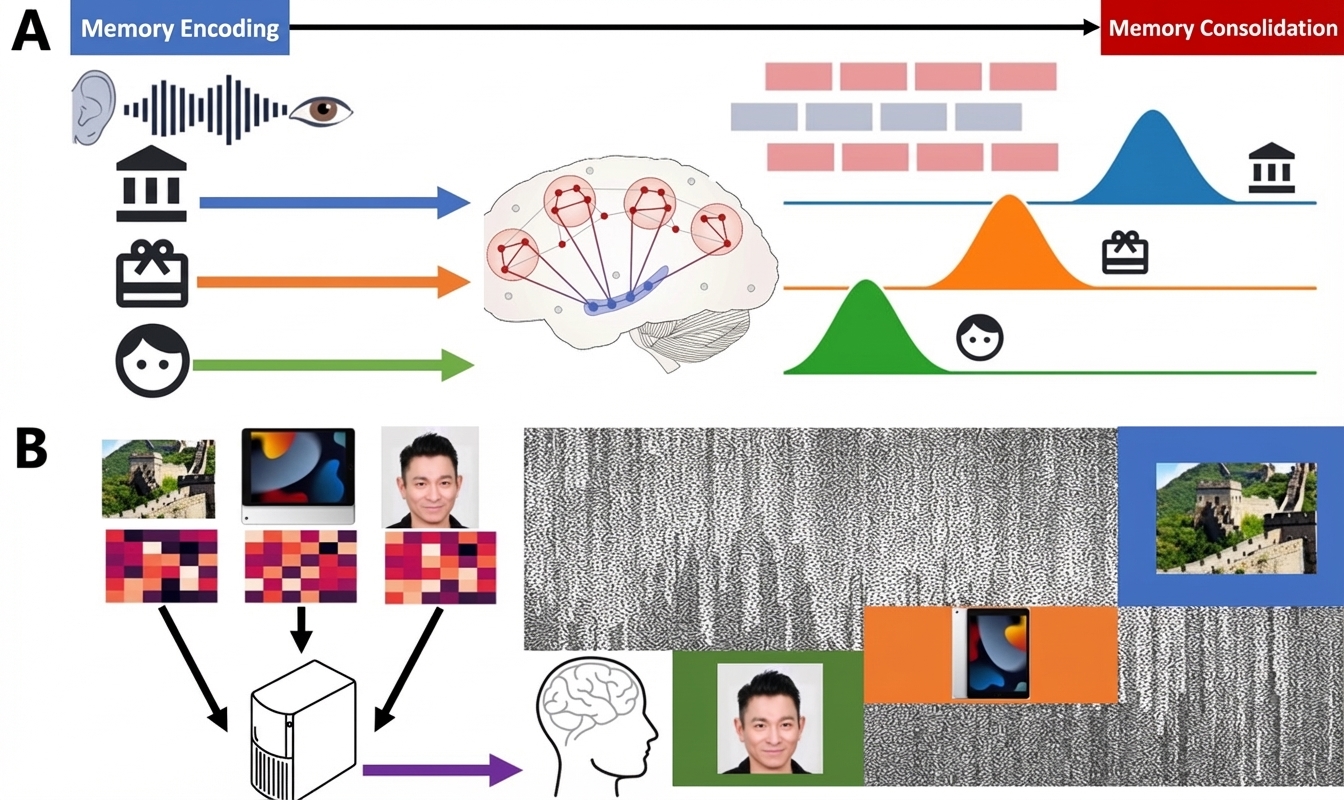

Figure 3. Characterizing Human Neural Replay During Memory Consolidation Using Neural Decoding and Computational Modeling. (A) After memory encoding, multiple memory information enters the consolidation phase. During this period, the hippocampus and widespread cortical regions interact, and memory information reappears in the brain in a certain order (forward or reverse). This phenomenon is called neural replay, considered a key neural process for memory consolidation. (B) To capture human neural replay in experimental data, we first need to establish associations between neural patterns and external stimuli (usually visual, such as locations, objects, faces), i.e., train machine learning algorithms to decode memory content. Then, by applying the machine learning algorithm to spontaneous neural activity during consolidation, we can obtain probability information about how various external stimuli are represented in the brain at specific time points. Finally, by further establishing sequential models of when different memories appear (Y. Liu, Dolan, et al., 2021; Y. Liu et al., 2022), we can quantify neural replay.

3.2 Study 2: How Do Altered Neural Replay Features Under Stress Relate to Different Memory Retrieval Tasks?

Study 2 examines how altered neural replay features under stress relate to performance on different memory retrieval tasks, using a 2 (stress condition: stress/non-stress) × 3 (memory retrieval task: recognition/selection retrieval/memory inference) within-subjects design. Building on Study 1, Study 2 adds a memory retrieval phase. Three memory retrieval paradigms (recognition, selection, and memory inference) will be used to quantify the formation/persistence, specificity, and flexibility of episodic memory, respectively. The specific testing order of the three paradigms will be balanced across participants to ensure equal probability of appearing at the beginning of the retrieval phase. In the recognition task (measuring memory formation/persistence), participants make old/new judgments on pictures, half of which did not appear during encoding. In the selection retrieval task (measuring memory specificity), participants are asked to select the previously learned picture from three similar pictures, with the other two serving as similar lure pictures. In the memory inference task (measuring memory flexibility/sequentiality), participants must flexibly retrieve information in sequence based on the encoded picture order. The research hypotheses are: (1) accelerated neural replay speed facilitates memory formation and persistence (using single-picture old/new recognition test performance as the memory index); (2) reduced neural replay accuracy impairs memory specificity (using multiple similar picture selection performance as the memory index); (3) disrupted neural replay sequentiality weakens memory flexibility (using sequence-based memory retrieval performance as the memory index).

3.3 Study 3: How Does Enhanced Memory Encoding Efficiency Before Stress Induction Affect Neural Replay Under Stress?

Study 3 investigates how enhancing memory encoding efficiency before stress induction affects neural replay under stress, using a 2 (encoding modulation strategy: retrieval practice/repeated study) × 2 (stress condition: stress/non-stress) mixed design, with encoding modulation strategy as a between-subjects variable. Building on Study 2, Study 3 incorporates manipulation of memory encoding efficiency before stress induction. Study 3 will explore how retrieval practice after encoding but before stress induction affects neural replay under stress. After memory encoding, participants will be randomly assigned to retrieval practice or repeated study groups. During the subsequent consolidation period, neural replay features will be quantified using EEG-recorded neural signals (same as Studies 1 and 2). In the final memory retrieval phase, fMRI will record prefrontal-hippocampal-amygdala activity and large-scale network interactions during memory retrieval. The key hypothesis is that retrieval practice can promote online memory consolidation, thereby completing consolidation before stress induction. Consolidated memories will be less affected by stress during the consolidation period and will perform similarly to non-stress conditions during retrieval.

3.4 Study 4: How Can Neural Replay Under Stress Be Modulated by Neuroendocrine and Environmental Strategies?

Study 4 aims to examine whether and how neural replay under stress can be modulated by external (neuroendocrine and environmental) strategies. On one hand, this provides causal evidence for altered neural replay features under stress; on the other hand, it lays the foundation for developing potential protective measures for memory function under stress. It includes two sub-experiments.

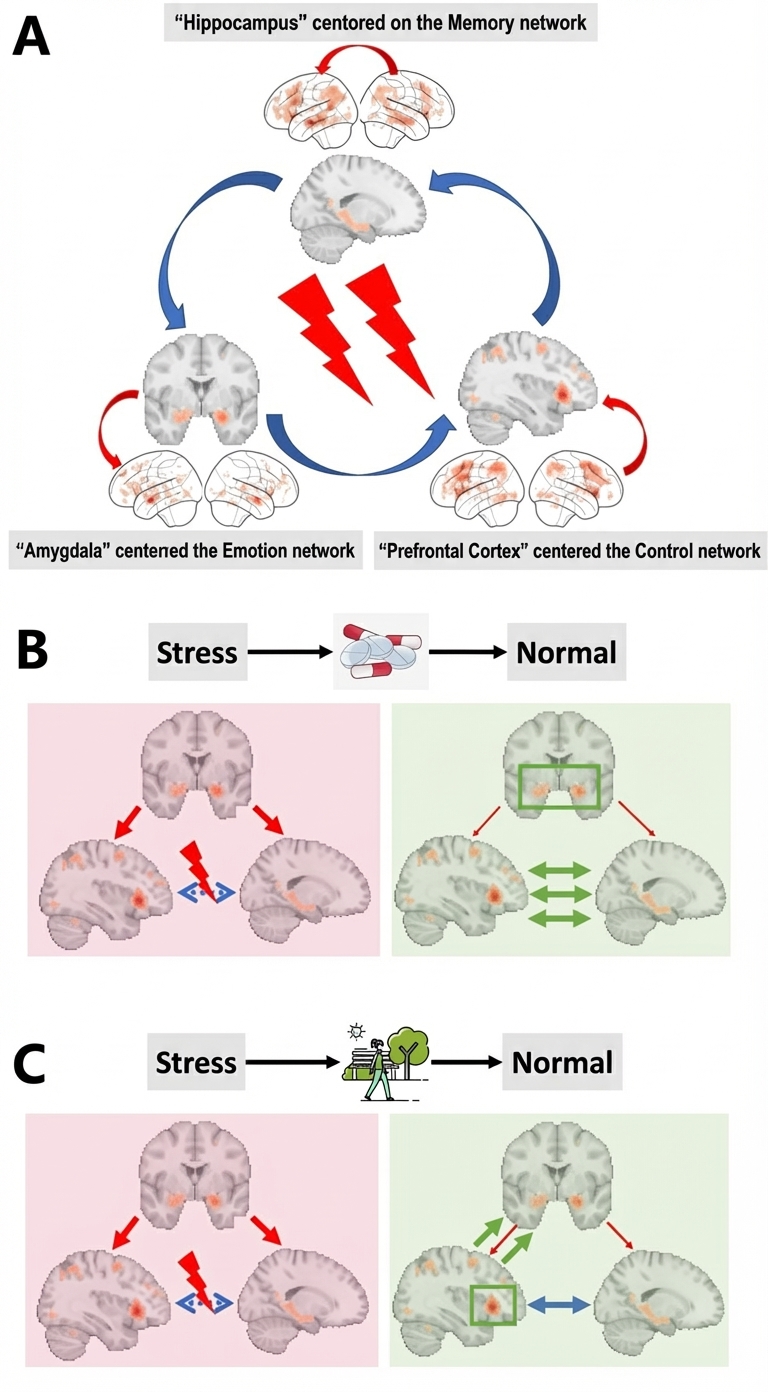

Experiment 4 uses a 2 (neuroendocrine modulation: propranolol/placebo) × 2 (stress condition: stress/non-stress) mixed design, with neuroendocrine modulation as a between-subjects variable and stress condition as a within-subjects variable. It aims to explore how oral administration of β-adrenergic receptor blocker (propranolol, also known as Inderal) one hour after encoding but before stress induction affects neural replay under stress. Similar to Study 3, after memory encoding, participants will be randomly assigned to drug intervention or placebo groups. The hypothesis is that neuroendocrine intervention can reduce cortisol levels in participants under stress, thereby protecting neural replay under stress and optimizing subsequent memory retrieval performance. From a brain network mechanism perspective, neuroendocrine strategies primarily restore normal function of the prefrontal-hippocampal memory circuit by inhibiting amygdala activity (Figure 4B).

Experiment 5 uses a 2 (environmental strategy: natural environment walk/urban environment walk) × 2 (stress condition: stress/non-stress) mixed design, with environmental strategy as a between-subjects variable and stress condition as a within-subjects variable. It explores how natural environment walking after encoding but before consolidation affects neural replay under stress. Participant recruitment, experimental procedures, stress induction and monitoring, and experimental tasks are identical to Experiment 4, with the only difference being that natural environment walking (environmental strategy) replaces neuroendocrine strategy. The core hypothesis is that natural environment walking before stress can enhance individual stress resistance, thereby reducing physiological responses under stress and achieving the goal of protecting neural replay under stress and optimizing memory retrieval. From a brain network mechanism perspective, we hypothesize that environmental strategies primarily restore normal activity of the prefrontal-hippocampal memory circuit by enhancing top-down prefrontal control over the amygdala (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Brain Network Interaction Patterns Under Stress and Their Modulation Mechanisms. (A) Memory function under stress mainly involves three networks: the memory network centered on the hippocampus, the emotional network centered on the amygdala, and the control network centered on the prefrontal cortex. (B) The possible neural mechanism of neuroendocrine strategy modulation of stress response: reducing amygdala activity to restore normal information interaction in the prefrontal-hippocampal circuit. (C) The possible mechanism of environmental strategy modulation of stress response: enhancing prefrontal activity and prefrontal control over the amygdala to restore normal activity in the prefrontal-hippocampal circuit.

4. Theoretical Framework

Previous animal experiments and some human studies suggest that stress may enhance memory consolidation. This study proposes a "double-edged sword" theoretical model (Figure 5), positing that stress has both enhancing and impairing effects on human memory consolidation, and designs corresponding empirical research for verification. Specifically, stress does not simply enhance (or impair) memory consolidation but can accelerate memory replay speed while potentially distorting memory content, including reduced memory accuracy and sequentiality. To experimentally verify this theory, the research design includes the following key points: (1) Exploration of neural replay metrics. The study will monitor and quantify neural replay features in participants under stress using neuroimaging techniques such as EEG, including replay speed, accuracy, and sequentiality. (2) Enriched memory retrieval paradigms. The experimental paradigm allows assessment of memory quality from multiple dimensions (persistence, specificity, and flexibility). Persistence tests evaluate whether participants can maintain memories long-term; specificity tests assess whether participants can accurately recall specific memory details rather than generalized or incorrect information; flexibility tests evaluate whether participants can flexibly use memory information for problem-solving or adapting to new situations. (3) Brain-behavior correlation analysis. Through analysis of memory retrieval test results, the study will identify specific behavioral consequences of altered neural replay features under stress. If neural replay speed indeed increases, memory retrieval persistence should be enhanced. Meanwhile, if neural replay accuracy and sequentiality decrease, specificity and flexibility should correspondingly weaken during retrieval.

Figure 5. The "Double-Edged Sword" Hypothesis of Stress Effects on Human Memory Consolidation. By collecting high-temporal-resolution EEG or MEG signals during memory consolidation, the project will use computational neuroscience tools to quantify neural replay speed, accuracy, and sequentiality. The theoretical hypothesis is that stress does not simply enhance (or impair) memory consolidation but accelerates neural replay speed while simultaneously disrupting its accuracy and sequentiality. To explore the behavioral consequences of altered neural replay metrics under stress, the project will use different paradigms during memory retrieval to test memory persistence, specificity, and flexibility.

The theoretical construction of this study has the following innovative aspects:

(1) Deepening understanding of human memory consolidation during wakefulness. This study will build upon the foundation of sleep memory consolidation research (Klinzing et al., 2019; Rasch et al., 2007), focusing on human memory consolidation processes during wakefulness and how these processes are affected by stress. Previous research has concentrated on memory consolidation mechanisms during sleep. Sleep is widely considered a critical period for memory consolidation, with neural replay activities occurring during sleep being essential for long-term memory storage (Wilhelm et al., 2011). However, falling asleep under stress is clearly not feasible for exploring stress effects on memory consolidation, making awake memory consolidation a more appropriate research window. This perspective broadens theoretical understanding of memory consolidation and has high practical significance for understanding memory mechanisms, considering that people frequently encounter stressful situations while awake in real life.

(2) Proposing multi-dimensional quantification methods for human memory consolidation and integrating animal and human memory replay research. Neural replay after memory encoding may be the neural basis of memory consolidation, but studying neural replay in humans has been extremely difficult. Early human memory consolidation research used resting-state fMRI to compare neural activity similarity between consolidation and encoding phases to describe consolidation processes (Tambini et al., 2010). In recent years, Liu et al. used machine learning and computational modeling to precisely quantify spontaneous neural activity during rest, characterizing the timing and specific sequence of neural replay (Y. Liu et al., 2019; Y. Liu, Dolan, et al., 2021; Y. Liu et al., 2022; Nour et al., 2021). These findings are similar to discoveries in rodent spatial memory replay (Carr et al., 2011; Davidson et al., 2009; Ji & Wilson, 2007; Karlsson & Frank, 2009). However, Liu et al.'s research primarily focused on whether neural replay exists, while this study proposes multi-dimensional quantification methods for neural replay signals to verify the "double-edged sword" hypothesis of stress effects on memory consolidation, simultaneously quantifying neural replay speed, accuracy, and sequentiality. The multi-dimensional quantification method for neural replay can integrate animal and human neural replay research because: on one hand, the proposed method can be transferred from human episodic memory research to quantifying animal spatial memory neural replay. Specifically, neural replay speed in animal electrophysiological data can be quantified using compression rate, neural replay accuracy can be quantified based on firing of irrelevant place cells when specific place cells fire, and neural replay sequentiality can be quantified based on similarity between place cell firing order during replay and spatial memory encoding. On the other hand, technological advances enable head-fixed mice to view different types of visual stimuli to simulate human episodic memory, making it easier to study visual-based episodic memory in animal models (Nguyen et al., 2023). For example, Nguyen observed stimulus-specific reactivations corresponding to specific visual stimuli during memory consolidation in animal models.

(3) Exploring novel stress modulation methods and their effects on human memory consolidation under stress. Memory consolidation can be modulated through optogenetics (Ego-Stengel & Wilson, 2009; Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2019), targeted memory reactivation (Hu et al., 2020), and non-invasive brain stimulation (Tambini & D'Esposito, 2020). This study focuses on how this special physiological-psychological state of stress affects memory consolidation. Additionally, this study will use neuroendocrine and environmental approaches to indirectly modulate memory consolidation by affecting stress responses, thereby addressing the increasingly severe stress and mental pressure that have become major factors threatening Chinese people's quality of life and mental health. This work promotes the development and practical application of novel stress modulation strategies, facilitating the translation of basic brain science research findings into the mental health domain.

Typically, memory consolidation is considered a lengthy process taking hours or even days. However, research shows that under specific conditions, such as stress states, memory can consolidate rapidly within minutes to hours. This project focuses on the neural mechanisms of rapid memory consolidation under stress conditions, integrating multidisciplinary methods including computational neuroscience, cognitive psychology, brain imaging, machine learning, neuroendocrine regulation, stress induction, and physiological-biochemical detection to examine how stress produces the "double-edged sword" effect that is both beneficial and detrimental to neural replay. This research is expected to provide new insights and strategies for protecting individual memory function in stressful environments and bring new concepts for memory rehabilitation in patients with stress-related psychiatric disorders. Simultaneously, it will help us more comprehensively understand neural replay phenomena in the brain and explore optimal brain states for promoting human memory function.

References

Ambrose, R. E., Pfeiffer, B. E., & Foster, D. J. (2016). Reverse replay of hippocampal place cells is uniquely modulated by changing reward. Neuron, 91(5), 1124–1136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016.07.047

Antony, J. W., Ferreira, C. S., Norman, K. A., & Wimber, M. (2017). Retrieval as a fast route to memory consolidation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(8), 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.05.001

Armario, A., Escorihuela, R. M., & Nadal, R. (2008). Long-term neuroendocrine and behavioural effects of a single exposure to stress in adult animals. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(6), 1121–1135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.003

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2648

Berman, M. G., Kardan, O., Kotabe, H. P., Nusbaum, H. C., & London, S. E. (2019). The promise of environmental neuroscience. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(5), 414–417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0577-7

Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral Sciences, 4(4), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs4040394

Bogdanov, M., & Schwabe, L. (2016). Transcranial stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex prevents stress-induced working memory deficits. The Journal of Neuroscience, 36(4), 1429–1437. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3687-15.2016

Buchanan, T. W., & Lovallo, W. R. (2001). Enhanced memory for emotional material following stress-level cortisol treatment in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 26(3), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00058-5

Cahill, L., Babinsky, R., Markowitsch, H. J., & McGaugh, J. L. (1995). The amygdala and emotional memory. Nature, 377(6547), 295–296. https://doi.org/10.1038/377295a0

Cahill, L., Gorski, L., & Le, K. (2003). Enhanced human memory consolidation with post-learning stress: Interaction with the degree of arousal at encoding. Learning & Memory, 10(4), 270–274. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.62403

Cahill, L., Haier, R. J., Fallon, J., Alkire, M. T., Tang, C., Keator, D., Wu, J., & McGaugh, J. L. (1996). Amygdala activity at encoding correlated with long-term, free recall of emotional information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(15), 8016–8021. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.15.8016

Cahill, L., Prins, B., Weber, M., & McGaugh, J. L. (1994). β-adrenergic activation and memory for emotional events. Nature, 371(6499), 702–704. https://doi.org/10.1038/371702a0

Carr, M. F., Jadhav, S. P., & Frank, L. M. (2011). Hippocampal replay in the awake state: A potential substrate for memory consolidation and retrieval. Nature Neuroscience, 14(2), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2732

Chang, J., Hu, J., Li, C.-S. R., & Yu, R. (2020). Neural correlates of enhanced response inhibition in the aftermath of stress. NeuroImage, 204, 116212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116212

Chang, J., & Yu, R. (2019). Hippocampal connectivity in the aftermath of acute social stress. Neurobiology of Stress, 11, 100195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100195

Cohen, J. D., Daw, N., Engelhardt, B., Hasson, U., Li, K., Niv, Y., Norman, K. A., Pillow, J., Ramadge, P. J., Turk-Browne, N. B., & Willke, T. L. (2017). Computational approaches to fMRI analysis. Nature Neuroscience, 20(3), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4499

Cousijn, H., Rijpkema, M., Qin, S., van Marle, H. J. F., Franke, B., Hermans, E. J., van Wingen, G., & Fernández, G. (2010). Acute stress modulates genotype effects on amygdala processing in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(21), 9867–9872. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1003514107

Davidson, T. J., Kloosterman, F., & Wilson, M. A. (2009). Hippocampal replay of extended experience. Neuron, 63(4), 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.027

de Kloet, E. R., Joëls, M., & Holsboer, F. (2005). Stress and the brain: From adaptation to disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(6), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1683

de Quervain, D. J.-F., Aerni, A., & Roozendaal, B. (2007). Preventive effect of β-Adrenoceptor blockade on glucocorticoid-induced memory retrieval deficits. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 967–969. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.967

de Quervain, D. J.-F., Roozendaal, B., & McGaugh, J. L. (1998). Stress and glucocorticoids impair retrieval of long-term spatial memory. Nature, 394(6695), 787–790. https://doi.org/10.1038/29542

Deisseroth, K. (2011). Optogenetics. Nature Methods, 8(1), 26–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.f.324

Dolcos, F., LaBar, K. S., & Cabeza, R. (2004). Interaction between the amygdala and the medial temporal lobe memory system predicts better memory for emotional events. Neuron, 42(5), 855–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00289-2

Duan, H., Wang, X., Hu, W., & Kounios, J. (2020). Effects of acute stress on divergent and convergent problem-solving. Thinking & Reasoning, 26(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2019.1572539

Duan, H., Wang, X., Wang, Z., Xue, W., Kan, Y., Hu, W., & Zhang, F. (2019). Acute stress shapes creative cognition in trait anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01517

Dupret, D., O'Neill, J., Pleydell-Bouverie, B., & Csicsvari, J. (2010). The reorganization and reactivation of hippocampal maps predict spatial memory performance. Nature Neuroscience, 13(8), 995–1002. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2599

Ego-Stengel, V., & Wilson, M. A. (2009). Disruption of ripple-associated hippocampal activity during rest impairs spatial learning in the rat. Hippocampus, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20707

Fernández, G., Effern, A., Grunwald, T., Pezer, N., Lehnertz, K., Dümpelmann, M., Van Roost, D., & Elger, C. E. (1999). Real-time tracking of memory formation in the human rhinal cortex and hippocampus. Science, 285(5433), 1582–1585. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.285.5433.1582

Fernández-Ruiz, A., Oliva, A., Fermino de Oliveira, E., Rocha-Almeida, F., Tingley, D., & Buzsáki, G. (2019). Long-duration hippocampal sharp wave ripples improve memory. Science, 364(6445), 1082–1086. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax0758

Ferreira, C. S., Charest, I., & Wimber, M. (2019). Retrieval aids the creation of a generalised memory trace and strengthens episode-unique information. NeuroImage, 202, 116085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.07.009

Foster, D. J., & Wilson, M. A. (2006). Reverse replay of behavioural sequences in hippocampal place cells during the awake state. Nature, 440(7084), 680–683. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04587

Fox, M. D., & Raichle, M. E. (2007). Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(9), 700–711. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2201

Frankland, P. W., & Bontempi, B. (2005). The organization of recent and remote memories. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1607

Frankland, P. W., Josselyn, S. A., & Köhler, S. (2019). The neurobiological foundation of memory retrieval. Nature Neuroscience, 22(10), 1576–1585. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0493-1

Gagnon, S. A., Waskom, M. L., Brown, T. I., & Wagner, A. D. (2019). Stress impairs episodic retrieval by disrupting hippocampal and cortical mechanisms of remembering. Cerebral Cortex, 29(7), 2947–2964. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhy162

Gärtner, M., Rohde-Liebenau, L., Grimm, S., & Bajbouj, M. (2014). Working memory-related frontal theta activity is decreased under acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 49, 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.02.009

Guerra-Carrillo, B., Mackey, A. P., & Bunge, S. A. (2014). Resting-state fMRI. The Neuroscientist, 20(5), 522–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858414524442

Hermans, E. J., Henckens, M. J. A. G., Joëls, M., & Fernández, G. (2014). Dynamic adaptation of large-scale brain networks in response to acute stressors. Trends in Neurosciences, 37(6), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2014.03.006

Hermans, E. J., van Marle, H. J. F., Ossewaarde, L., Henckens, M. J. A. G., Qin, S., van Kesteren, M. T. R., Schoots, V. C., Cousijn, H., Rijpkema, M., Oostenveld, R., & Fernández, G. (2011). Stress-related noradrenergic activity prompts large-scale neural network reconfiguration. Science, 334(6059), 1151–1153. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1209603

Hu, X., Cheng, L. Y., Chiu, M. H., & Paller, K. A. (2020). Promoting memory consolidation during sleep: A meta-analysis of targeted memory reactivation. Psychological Bulletin, 146(3), 218–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000223

Inman, C. S., Manns, J. R., Bijanki, K. R., Bass, D. I., Hamann, S., Drane, D. L., Fasano, R. E., Kovach, C. K., Gross, R. E., & Willie, J. T. (2018). Direct electrical stimulation of the amygdala enhances declarative memory in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(1), 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1714058114

Ji, D., & Wilson, M. A. (2007). Coordinated memory replay in the visual cortex and hippocampus during sleep. Nature Neuroscience, 10(1), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1825

Karlsson, M. P., & Frank, L. M. (2009). Awake replay of remote experiences in the hippocampus. Nature Neuroscience, 12(7), 913–918. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2344

Klinzing, J. G., Niethard, N., & Born, J. (2019). Mechanisms of systems memory consolidation during sleep. Nature Neuroscience, 22(10), 1598–1610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0467-3

Kurth-Nelson, Z., Behrens, T., Wayne, G., Miller, K., Luettgau, L., Dolan, R., Liu, Y., & Schwartenbeck, P. (2023). Replay and compositional computation. Neuron, 111(4), 512–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2022.12.028

LaBar, K. S., & Cabeza, R. (2006). Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1825

Lederbogen, F., Kirsch, P., Haddad, L., Streit, F., Tost, H., Schuch, P., Wüst, S., Pruessner, J. C., Rietschel, M., Deuschle, M., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2011). City living and urban upbringing affect neural social stress processing in humans. Nature, 474(7352), 498–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10190

Lee, K. O., Mai, K. M., & Park, S. (2023). Green space accessibility helps buffer declined mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from big data in the United Kingdom. Nature Mental Health, 1(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00018-y

Lindauer, R. J. L., Olff, M., van Meijel, E. P. M., Carlier, I. V. E., & Gersons, B. P. R. (2006). Cortisol, learning, memory, and attention in relation to smaller hippocampal volume in police officers with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 59(2), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.033

Liu, F., Xu, J., Guo, L., Qin, W., Liang, M., Schumann, G., & Yu, C. (2023). Environmental neuroscience linking exposome to brain structure and function underlying cognition and behavior. Molecular Psychiatry, 28(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01669-6

Liu, W., Kohn, N., & Fernández, G. (2019). Intersubject similarity of personality is associated with intersubject similarity of brain connectivity patterns. NeuroImage, 186, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.10.062

Liu, W., Kohn, N., & Fernández, G. (2021). Dynamic transitions between neural states are associated with flexible task switching during a memory task. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 33(12), 2559–2588. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01779

Liu, W., Shi, Y., Cousins, J. N., Kohn, N., & Fernández, G. (2022). Hippocampal-medial prefrontal event segmentation and integration contribute to episodic memory formation. Cerebral Cortex, 32(5), 949–969. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab258

Liu, Y., Dolan, R. J., Higgins, C., Penagos, H., Woolrich, M. W., Ólafsdóttir, H. F., Barry, C., Kurth-Nelson, Z., & Behrens, T. E. (2021). Temporally delayed linear modelling (TDLM) measures replay in both animals and humans. ELife, 10, e66917. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.66917

Liu, Y., Dolan, R. J., Kurth-Nelson, Z., & Behrens, T. E. J. (2019). Human replay spontaneously reorganizes experience. Cell, 178(3), 640-652.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.012

Liu, Y., Mattar, M. G., Behrens, T. E. J., Daw, N. D., & Dolan, R. J. (2021). Experience replay is associated with efficient nonlocal learning. Science, 372(6544), eabf1357. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf1357

Liu, Y., Nour, M. M., Schuck, N. W., Behrens, T. E. J., & Dolan, R. J. (2022). Decoding cognition from spontaneous neural activity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 23(4), 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-022-00570-z

Luo, Y., Fernández, G., Hermans, E., Vogel, S., Zhang, Y., Li, H., & Klumpers, F. (2018). How acute stress may enhance subsequent memory for threat stimuli outside the focus of attention: DLPFC-amygdala decoupling. NeuroImage, 171, 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.010

McCullough, A. M., Ritchey, M., Ranganath, C., & Yonelinas, A. (2015). Differential effects of stress-induced cortisol responses on recollection and familiarity-based recognition memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 123, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2015.04.007

McCutcheon, R. A., Reis Marques, T., & Howes, O. D. (2020). Schizophrenia—An overview. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3360

McGaugh, J. L. (2003). Memory and emotion: The making of lasting memories. Columbia University Press.

McGaugh, J. L. (2018). Emotional arousal regulation of memory consolidation. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 19, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.10.003

Murayama, K., & Kitagami, S. (2014). Consolidation power of extrinsic rewards: Reward cues enhance long-term memory for irrelevant past events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031992

Murayama, K., & Kuhbandner, C. (2011). Money enhances memory consolidation—But only for boring material. Cognition, 119(1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2011.01.001

Newcomer, J. W., Selke, G., Melson, A. K., Hershey, T., Craft, S., Richards, K., & Alderson, A. L. (1999). Decreased memory performance in healthy humans induced by stress-level cortisol treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(6), 527–533.

Nour, M. M., Liu, Y., Arumuham, A., Kurth-Nelson, Z., & Dolan, R. J. (2021). Impaired neural replay of inferred relationships in schizophrenia. Cell, 184(16), 4315-4328.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.012

Nguyen, N. D., Lutas, A., Amsalem, O., et al. (2023). Cortical reactivations predict future sensory responses. Nature, 618(7965), 518–525. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06810-1

Qin, S., Hermans, E. J., van Marle, H. J. F., Luo, J., & Fernández, G. (2009). Acute psychological stress reduces working memory-related activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Biological Psychiatry, 66(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.006

Rao, R. P., Anilkumar, S., McEwen, B. S., & Chattarji, S. (2012). Glucocorticoids protect against the delayed behavioral and cellular effects of acute stress on the amygdala. Biological Psychiatry, 72(6), 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.008

Rasch, B., Büchel, C., Gais, S., & Born, J. (2007). Odor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidation. Science, 315(5817), 1426–1429. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1138581

Roozendaal, B., Okuda, S., de Quervain, D. J.-F., & McGaugh, J. L. (2006). Glucocorticoids interact with emotion-induced noradrenergic activation in influencing different memory functions. Neuroscience, 138(3), 901–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.049

Schuck, N. W., & Niv, Y. (2019a). Sequential replay of nonspatial task states in the human hippocampus. Science, 364(6447), eaaw5181. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw5181

Schwabe, L., Hermans, E. J., Joëls, M., & Roozendaal, B. (2022). Mechanisms of memory under stress. Neuron, 110(9), 1450–1467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2022.02.020

Schwabe, L., Römer, S., Richter, S., Dockendorf, S., Bilak, B., & Schächinger, H. (2009). Stress effects on declarative memory retrieval are blocked by a β-adrenoceptor antagonist in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(3), 446–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.009

Sharot, T., & Phelps, E. A. (2004). How arousal modulates memory: Disentangling the effects of attention and retention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 4(3), 294–306. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.4.3.294

Squire, L. R., Genzel, L., Wixted, J. T., & Morris, R. G. (2015). Memory consolidation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(8), a021766. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a021766

Sudimac, S., Sale, V., & Kühn, S. (2022). How nature nurtures: Amygdala activity decreases as the result of a one-hour walk in nature. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(11), 4445–4446. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01720-6

Suh, J., Foster, D. J., Davoudi, H., Wilson, M. A., & Tonegawa, S. (2013). Impaired hippocampal ripple-associated replay in a mouse model of schizophrenia. Neuron, 80(2), 484–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.014

Takashima, A., Nieuwenhuis, I. L. C., Jensen, O., Talamini, L. M., Rijpkema, M., & Fernández, G. (2009). Shift from hippocampal to neocortical centered retrieval network with consolidation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(32), 10087–10093. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0799-09.2009

Takashima, A., Petersson, K. M., Rutters, F., Tendolkar, I., Jensen, O., Zwarts, M. J., McNaughton, B. L., & Fernández, G. (2006). Declarative memory consolidation in humans: A prospective functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(3), 756–761. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507774103

Tambini, A., & D'Esposito, M. (2020). Causal contribution of awake post-encoding processes to episodic memory consolidation. Current Biology, 30(18), 3533-3543.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.063

Tambini, A., & Davachi, L. (2013). Persistence of hippocampal multivoxel patterns into postencoding rest is related to memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(48), 19591–19596. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1308499110

Tambini, A., & Davachi, L. (2019). Awake reactivation of prior experiences consolidates memories and biases cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(10), 876–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.07.008

Tambini, A., Ketz, N., & Davachi, L. (2010). Enhanced brain correlations during rest are related to memory for recent experiences. Neuron, 65(2), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.001

Tambini, A., Rimmele, U., Phelps, E. A., & Davachi, L. (2017). Emotional brain states carry over and enhance future memory formation. Nature Neuroscience, 20(2), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4468

Tost, H., Champagne, F. A., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2015). Environmental influence in the brain, human welfare and mental health. Nature Neuroscience, 18(10), 1421–1431. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4108

Tse, D., Langston, R. F., Kakeyama, M., Bethus, I., Spooner, P. A., Wood, E. R., Witter, M. P., & Morris, R. G. M. (2007). Schemas and memory consolidation. Science, 316(5821), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1135935

van Kesteren, M. T. R., Fernández, G., Norris, D. G., & Hermans, E. J. (2010). Persistent schema-dependent hippocampal-neocortical connectivity during memory encoding and postencoding rest in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(16), 7550–7555. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0914892107

van Marle, H. J. F., Hermans, E. J., Qin, S., & Fernández, G. (2009). From specificity to sensitivity: How acute stress affects amygdala processing of biologically salient stimuli. Biological Psychiatry, 66(7), 649–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.014

Wamsley, E. J. (2022). Offline memory consolidation during waking rest. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(8), 441–453. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00072-w

Wilhelm, I., Diekelmann, S., Molzow, I., Ayoub, A., Mölle, M., & Born, J. (2011). Sleep selectively enhances memory expected to be of future relevance. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(5), 1563–1569. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3575-10.2011

Wittkuhn, L., & Schuck, N. W. (2021). Dynamics of fMRI patterns reflect sub-second activation sequences and reveal replay in human visual cortex. Nature Communications, 12(1), 1795. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21970-2

Wolf, O. T. (2017). Stress and memory retrieval: Mechanisms and consequences. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 14, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.12.001

Xu, J., Liu, X., Li, Q., Goldblatt, R., Qin, W., Liu, F., Chu, C., Luo, Q., Ing, A., Guo, L., Liu, N., Liu, H., Huang, C., Cheng, J., Wang, M., Geng, Z., Zhu, W., Zhang, B., Liao, W., … Schumann, G. (2021). Global urbanicity is associated with brain and behaviour in young people. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(2), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01204-7

Ye, Z., Shi, L., Li, A., Chen, C., & Xue, G. (2020). Retrieval practice facilitates memory updating by enhancing and differentiating medial prefrontal cortex representations. ELife, 9, e57023. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57023

Yuen, E. Y., Liu, W., Karatsoreos, I. N., Feng, J., McEwen, B. S., & Yan, Z. (2009). Acute stress enhances glutamatergic transmission in prefrontal cortex and facilitates working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(33), 14075–14079. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906791106

Zhuang, L., Wang, J., Xiong, B., Bian, C., Hao, L., Bayley, P. J., & Qin, S. (2021). Rapid neural reorganization during retrieval practice predicts subsequent long-term retention and false memory. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(1), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01188-4

Zinkin, S., & Miller, A. J. (1967). Recovery of memory after amnesia induced by electroconvulsive shock. Science, 155(3758), 102–104. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.155.3758.102