Abstract

With popular terms such as "tool person," "wage slave," and "corporate livestock" sweeping through the workplace, workplace objectification has become a topic that urgently requires exploration. As the use of artificial intelligence, especially robots, in the workplace continues to increase, robot-generated workplace effects are also worthy of attention. Therefore, this project aims to investigate whether the infiltration of robots into the workplace will produce or exacerbate workplace objectification phenomena in the context of rapidly developing artificial intelligence. Based on intergroup threat theory and compensatory control theory, we hypothesize that the salience of robot employees in the workplace will increase workplace objectification. The project utilizes a combination of experiments, big data, and questionnaire surveys; first, it examines whether the salience of robot employees increases workplace objectification to provide preliminary verification of the effect; then it explores the mediating mechanisms through which robots influence workplace objectification, seeking to identify the sequential mediating effects of perceived threat and control compensation; finally, it examines the moderating effects of individual, robot, and environmental factors on the influence of robots on workplace objectification, and discusses intervention strategies for workplace objectification from the perspective of organizational culture. This exploration will contribute to a forward-looking understanding of the potential negative effects of artificial intelligence in the workplace within the context of artificial intelligence and particularly robot development, and to propose effective solutions.

Full Text

Screws in the Age of Wisdom: The Influence of Robot Salience on Workplace Objectification

XU Liying¹, YU Feng²*, PENG Kaiping¹, WANG Xuehui¹

¹ Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China

² Department of Psychology, School of Philosophy, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China

Abstract: With buzzwords such as "tool person," "wage slave," and "corporate livestock" sweeping through contemporary workplaces, workplace objectification has become an urgent topic for discussion. As artificial intelligence, particularly robots, becomes increasingly prevalent in work settings, the workplace effects produced by robots also warrant attention. Therefore, this project aims to explore whether the penetration of robots into the workplace generates or exacerbates workplace objectification in today's society where AI is rapidly developing. Based on intergroup threat theory and compensatory control theory, we hypothesize that the salience of robot workers in the workplace will increase workplace objectification. The project employs a combination of experiments, big data analysis, and questionnaire surveys. First, it examines whether robot salience increases workplace objectification to initially verify the effect. Second, it explores the mediating mechanisms underlying robot influence on workplace objectification, attempting to identify a chain mediating effect of perceived threat and compensatory control. Finally, it investigates moderating effects from three perspectives—individual, robot, and environment—on how robots influence workplace objectification, and explores intervention strategies for workplace objectification from an organizational culture perspective. This exploration will help prospectively understand the potential negative effects of AI, particularly robots, in the workplace and propose effective solutions.

Keywords: workplace objectification, robot, compensatory control theory, morality

1. Problem Statement

In modern society, workplace professionals inevitably work alongside machines. From agriculture to industry to services, from office workers to factory laborers, from small computers to large industrial and agricultural machinery, workplaces are filled with various machines. To some extent, as Max Weber (1904/2010) noted, the disenchanted rationalization of modern society has transformed social division of labor into a finely-tuned, smoothly operating machine, and people in modern workplaces have become components of this machine. Workers have become parts of the machine, and labor has consequently shifted from spontaneous instinct to instrumental function. Workers themselves begin to view themselves according to the commodities they produce and their value, thereby defining their humanity through the goods they create—this is what Marx called alienation (Marx, 1844/1964). Today, the situation differs: not only do people resemble machines, but machines also resemble people. Machines that are like humans do not necessarily mimic human appearance (Xu et al., 2017), but rather human-like intelligence—this is artificial intelligence (Yu & Xu, 2020). AI enters human workplaces through robots or intelligent programs. Beyond traditional labor such as grasping, lifting, supporting, and carrying, it can assist in data capture, real-time monitoring, intelligent selection, and decision support. It may help screen resumes, assign tasks, or even strategize for a company's future. The entry of robots into the workplace has sparked widespread societal discussion (e.g., Chamorro-Premuzic et al., 2019 at Harvard Business Review; Kelion, 2019 at BBC; Martinez, 2019 at Forbes; Abril, 2019 at Fortune). As machines enter the workplace as quasi-"persons," will this change relationships between people? Will individuals in the workplace view their colleagues differently due to the emergence of robots and the increasingly blurred boundaries between humans and machines?

This is inevitable. Concern for this issue precisely addresses the need to "strengthen research on AI-related legal, ethical, and social issues" while "deepening the integration of AI with efforts to safeguard and improve people's livelihood, and promote the deep application of AI in people's daily work, study, and life to create more intelligent ways of working and living" (Xi Jinping, 2018, at the ninth collective study session of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee). When people become machines and machines become people, will this cause human nature to wither and alter interpersonal relationships? The most straightforward consideration is that people anthropomorphize machines while mechanizing people in the workplace—mechanization being a form of objectification (Andrighetto et al., 2017). That humans are not objects is humanity's pride. Renaissance humanism advocated for individual personality and emphasized maintaining human dignity. Yet the tide of the Industrial Revolution submerged individual persons in the massive machinery of society, playing the role of screws. Workplace objectification occurs against this backdrop. When we say someone is not human, it is filled with negativity, contempt, and mockery—but do we truly treat people as human?

Among the "Top 10 Internet Buzzwords of 2020," "tool person" made the list and has become workplace slang. In the workplace, people not only view each other as "tool persons" but also self-mockingly refer to themselves as such—this is clearly objectification of people.

It is already foreseeable that AI will greatly integrate into people's lives, profoundly changing them and even altering how people perceive themselves and others. AI's own development will inevitably lead to a human-centered developmental form that interacts with people, embedding itself in various ways to create a new mode of existence. This new mode of existence will inevitably lead to new relationship patterns, new ethical models, new interaction patterns, and new cognitive patterns. Therefore, concerns about potential social problems arising from AI, particularly robots, have long accompanied its development. Technological progress is important, but development that loses sight of "people" themselves may spiral out of control. The rise of robots as workers has already triggered human anxiety (e.g., Smith & Anderson, 2017), not only due to robots' real threats to human employment and safety but also because robots may threaten human identity and uniqueness (Yogeeswaran et al., 2016)—something previous industrial revolutions never produced. Discussion on how robots in the workplace shape social relationships remains inconclusive, but because robots' occupation of jobs intensifies competition between people, this leads to negative impacts on interpersonal relationships. Similar threat outcomes include increasing people's material insecurity, causing them to perceive greater threat from immigrants and foreign workers, thereby increasing support for anti-immigration policies (e.g., Frey et al., 2018; Im et al., 2019). Therefore, this project hypothesizes that robot salience in the workplace will generate or aggravate workplace objectification through psychological threat and post-threat control compensation mechanisms, moderated by personal, machine, and environmental factors. It should be noted that "robot salience" in this project refers to robots entering the workplace and attracting human attention, encompassing not only an increase in the proportion of robots in the workplace but also enhanced levels of robot work participation. Exploring this issue will help deepen understanding of workplace objectification in the context of AI development, prospectively understand the potential negative effects of AI, particularly robots, in the workplace, and propose effective countermeasures.

2.1 Workplace Objectification as the Core of Objectification but Neglected in Research

Objectification originated as a product of social critique, rooted in the human condition within capitalist society. Its core lies in people becoming parts of the social machine. However, the term has remained biased in psychological research, becoming a description exclusively of women's circumstances. This may stem from American contemporary feminist philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who detailed objectification's characteristics: (1) instrumentality—treating the objectified as tools for one's own purposes; (2) denial of autonomy—viewing the objectified as lacking self-determination; (3) inertness—perceiving the objectified as lacking agency and perhaps liveliness; (4) fungibility—believing the objectified can be replaced by other objects of the same or different type; (5) violability—believing the objectified lack boundary-integrity and that harming them is permissible; (6) ownership—treating the objectified as property that can be bought and sold; and (7) denial of subjectivity—believing the objectified's experiences and feelings need not be considered (Nussbaum, 1995, 1999). Nussbaum's definition actually contains no inherent bias toward women, as applying one or more of these characteristics to someone may constitute objectification (Nussbaum, 1995, 1999). The meaning of objectification in psychology has not transcended Nussbaum's framework.

Due to intensified American societal pursuit of democracy, equal rights, and identity concepts in the mid-20th century, alongside feminist movements (e.g., MacKinnon, 1989) and increasingly prevalent and severe sexual objectification, psychological research on objectification focused on sexual objectification, with the most influential objectification theory limited to examining sexual objectification of women (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Sexual objectification refers to "a woman's body, body parts, or sexual functions being separated from the woman herself, reduced to mere instruments, or regarded as capable of representing the woman as an individual" (Bartky, 1990; Sun et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2015). Unfortunately, other forms of objectification have been neglected. In terms of research volume, most objectification studies to date remain focused on sexual objectification (Andrighetto et al., 2017). An analysis of existing objectification research reveals Figure 1's intuitive demonstration of the extreme bias toward female sexual objectification. It should be noted that although "objectification" is sometimes translated as "物化" (wùhuà) in Chinese psychological literature (e.g., Yang et al., 2015), it is more commonly rendered as "客体化" (kètǐhuà) (e.g., Jiang & Chen, 2019), a translation that poses problems. While "object" can mean either physical object or other, object distinguishes humans from other entities, whereas other distinguishes people from one's own subject. In fact, the self still has distinctions between subject-I and object-I (James, 1890), and turning people into perceptual objects has absolutely no objectification meaning. Sexual objectification is actually just a special case of the objectification concept. Therefore, this project adopts the "物化" (objectification) translation.

Figure 1. Hotspot Analysis of Objectification Research. Note: Using VOSviewer software (Van Eck & Waltman, 2010), we visualized 2,895 SCI, SSCI, and A&HCI publications from Web of Science (WoS) database (as of January 22, 2021) with "objectification" as the subject category, generating a keyword co-occurrence network visualization map. The visualization shows that the vast majority of keywords in foreign objectification research relate to female sexual objectification, such as women, self-objectification (generally referring to women's self-objectification), objectification theory, body image, etc. If searching CNKI with "客体化" in titles and "psychology" as the journal source (fuzzy search) (as of January 22, 2021), 31 results appear; except for one irrelevant popular science article, the remaining 30 articles all concern sexual objectification of women.

As described above, workplace objectification has been neglected by objectification research, particularly from the female perspective. In fact, objectification should be a broader concept capable of explaining wider social problems (Belmi & Schroeder, 2021), such as labor relations (e.g., economic objectification; Marx, 1844/1964; Gruenfeld et al., 2008), slavery (Heath & Schneewind, 1997), prejudice (Gray et al., 2011), etc. Confining objectification research to sexual objectification of women not only limits the objects of objectification (to women) but also restricts the types of objectification (to sexuality-related), which is detrimental to the comprehensive development of objectification research and loses the possibility of using objectification to understand and warn against broader social problems. Therefore, this project focuses on workplace objectification. Combining existing research on workplace objectification (e.g., Baldissarri et al., 2014; Belmi & Schroeder, 2021), this project defines workplace objectification as: the process and tendency to treat people as objects in the workplace, primarily reflecting instrumentality in work relationships and the denial of humanity. The main form of workplace objectification is instrumentalization; its direction may be downward (e.g., leaders toward employees), parallel (e.g., among employees, between employees and customers, or even between ordinary people and employees), or upward (employees toward leaders); its objects are not limited to women but include both genders.

Additionally, it should be emphasized that the workplace objectification studied in this project focuses primarily on the individual level—the degree to which individuals in the workplace objectify others—and explores the psychological mechanisms underlying this phenomenon.

However, despite long-standing and not uncommon theoretical reflections on workplace objectification (e.g., Kant, Marx, Fromm), empirical research on workplace objectification remains in its infancy (Baldissarri et al., 2014). Existing empirical research on workplace objectification mainly falls into two categories: antecedent exploration, which attempts to identify factors influencing workplace objectification; and consequence exploration, which attempts to identify outcomes of workplace objectification. A summary of workplace objectification research is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Workplace Objectification Research

Problem Existing Conclusions (1) Human Factors Such as power (Gruenfeld et al., 2008; Gwinn et al., 2013; Inesi et al., 2014), love of money (Wang & Krumhuber, 2017), desire for successful interaction with others but uncertainty about one's ability to control them (Landau et al., 2012), etc. (2) Work Factors Specific job characteristics such as repetitiveness, dependence on machines, and task fragmentation and compartmentalization (Andrighetto et al., 2017; Andrighetto et al., 2018; Baldissarri et al., 2017), work environments such as office anonymity (Taskin et al., 2019), dirty environments (Valtorta et al., 2019), or even simply being in a work context (Belmi & Schroeder, 2021), etc. (1) Self-Objectification When employees feel their leaders view them merely as tools (Auzoult & Personnaz, 2016; Baldissarri et al., 2014), or even simply recalling their own experiences of being objectified at work (Loughnan et al., 2017), leads to self-objectification. (2) Negative Psychology Workplace objectification is significantly correlated with depression and job satisfaction (Szymanski & Feltman, 2015), well-being and job performance (Caesens et al., 2017), salary estimates (Rollero & Tartaglia, 2013), etc. (3) Specific Behaviors Such as conformity (Andrighetto et al., 2018; Baldissarri et al., 2020) and higher aggression (Poon et al., 2020), etc.2.2 Robots Entering the Workplace Pose Threats but Have Not Received Sufficient Attention

In recent years, an increasing number of robots have entered workplaces, working alongside humans as new types of employees and even replacing some human workers. Since the birth of the first robot, the complexity of tasks robots perform and their autonomy have steadily increased (Murashov et al., 2016), enabling robots to handle more human jobs and enter broader workplace fields, thereby posing increasingly severe threats to humans. However, although some social surveys show the public already worries about robot threats (e.g., Smith, 2016; Smith & Anderson, 2017), empirical research on whether such threats truly exist, whether and to what extent people perceive these threats, and what impacts these threats may cause remains very limited. Robot applications in workplaces are increasing, and robots can be mainly divided into two types: industrial robots and service robots. The research objects in this project include both industrial and service robots, but primarily focus on service robots programmed to replicate human functions in workplace settings. It should be noted that the robots studied in this project do not necessarily have anthropomorphic appearances and may be operated by humans or run autonomously.

Today, robots have entered nearly every domain of human work. In industrial sectors, robots are no longer as conspicuous as when they first appeared; they are now considered a natural and indispensable part of the industrial sector (Salzmann-Erikson & Eriksson, 2016). The rampant COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted many industries, yet the disinfection robot market has bucked the trend, with demand for service robots surging in warehouses, factories, and delivery services (International Federation of Robotics, 2020).

In the critical healthcare domain, robots have also become an indispensable component, with applications ranging from preliminary diagnosis to minimally invasive and precise robotic surgery, and serving as intervention and treatment tools for behavioral disorders, disabilities, and rehabilitation (Agnihotri & Gaur, 2016). Research shows that compared to non-robotic surgery, robot-assisted surgery can reduce patient hospital stays and lower complication and mortality rates (Yanagawa et al., 2015). The world's aging population and shortage of healthcare professionals have increased the need for assistive technologies and robots in various healthcare fields, such as elderly care, stroke rehabilitation, and primary care (Vermeersch et al., 2015). For ordinary people, robots in the service industry are even more common. Service robots can now help customers select wine at airport duty-free shops (Changi Journeys, 2019), pull 1,000-liter trash bins along pre-planned routes for cleaning (Yi, 2019), or even issue tickets to traffic violators (Kaur, 2019). Humanoid robots are most widely used in the service industry. Take the humanoid robot "Pepper" as an example: since its launch in 2014, over 10,000 Pepper robots have been sold globally, generating $140 million in sales and related service revenue (Frank, 2016). Pepper has helped sell coffee machines at 1,000 Nestlé coffee shops in Japan (Nestlé, 2014) and served as a waiter at Pizza Hut in Asia (Sophie, 2016) and a restaurant at Auckland International Airport, taking orders and interacting with customers (e.g., recommending food; Brian, 2017). Moreover, robots have entered virtually every aspect of human work and life, such as military (e.g., Lin et al., 2008), education (e.g., Leyzberg et al., 2014; Ritschel, 2018), law (e.g., Xu & Wang, 2019), corporate recruitment (e.g., Nawaz, 2019), and even management positions with higher cognitive demands (e.g., Dixon et al., 2021). In summary, robots currently appear in many work domains, and as robot technology continues to develop, the ranks of robot workers will undoubtedly further expand.

As the ranks of robot workers continue to grow, so do the threats humans face in the workplace. Psychological research on intergroup relations shows that people distinguish between ingroups (groups individuals identify with or "us") and outgroups (groups individuals do not identify with or "them") (Hewstone et al., 2002). This distinction also applies in human-robot interaction, where robots may be viewed as an outgroup distinct from the human group. According to intergroup threat theory (Stephan et al., 2015), people perceive different threats from outgroups, including realistic threat and symbolic threat. Realistic threat is a form of resource threat involving physical harm to the ingroup and threats to ingroup power, resources, and well-being (Stephan et al., 2015). Therefore, when robots are perceived as threatening human jobs, material resources, or safety, they may be viewed as a realistic threat to humans. Symbolic threat refers to threats to ingroup identity, values, and distinctiveness (Stephan et al., 2015). Because people are motivated to view their group as distinct from other outgroups (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), when robots are highly similar to humans and integrate into society, they may be perceived not only as realistic threats to human work and resources but also as threats to human identity because they blur the boundary between humans and machines (Yogeeswaran et al., 2016).

On one hand, robot workers pose realistic threats to humans. As mentioned earlier, with advances in robotics, more robots have entered human work domains. A public social survey found that as many as two-thirds of Americans expect "robots and computers will do most of the work currently done by humans within 50 years" (Smith, 2016). Another survey found that as many as 72% of American respondents worry that computers and robots will be able to do more human work in the future, while 85% support policies limiting machines in dangerous jobs (Smith & Anderson, 2017). A 2017 McKinsey report also estimated that 50% of human work could be automated using current robotics technology (Manyika et al., 2017). This means more robots will appear in workplaces, triggering more severe job competition between humans and robots. In many respects, robots may be more efficient, reliable, and economical than humans. First, robots are easier to manage: robot "employees" neither arrive late nor conflict with colleagues. Second, although purchase, leasing, and maintenance costs may currently be high, as robotics technology matures, costs will decrease. Most importantly, employers do not need to pay benefits to robots (Borenstein, 2011), meaning robots' work costs may be lower than any human labor costs, while their working hours will inevitably be longer than any human workforce (McClure, 2018). These factors may lead employers to increasingly prefer replacing human employees with robot workers. Additionally, we should not overlook that certain human labor groups may face relatively greater threats from robot workers. For example, the automotive industry is the most extensive user of industrial robots, with nearly 28% of industrial robots installed in automotive factories (International Federation of Robotics, 2020). Although design and maintenance remain human employee "territory," it is undeniable that large numbers of manual laborers on production lines have been replaced by robots, among which older, less-educated employees often have weaker learning abilities and struggle to adapt to new technological developments, making them more vulnerable "high-threat" populations (Borenstein, 2011). Beyond threatening human jobs, robot workers may also pose certain safety threats. Many film and television works such as Ex Machina and I, Robot express human fears of robots threatening human safety. While striving to make robots smarter, humans also worry that robots may become too intelligent and threaten humanity itself (Salzmann-Erikson & Eriksson, 2016). If science fiction and films seem too illusory, robots currently appearing in various workplaces and public spaces may also threaten human safety. As more mobile robots have direct contact with humans, concerns about safety in interaction spaces have increased (Murashov et al., 2016).

On the other hand, robot workers pose identity threats to humans. Robots' identity threat to humans mainly stems from their abilities and appearance similarity to humans blurring the boundary between humans and machines. Some anthropomorphic robots' appearances are almost indistinguishable from humans, and some robots' abilities rival or surpass humans, threatening humans' sense of identity and uniqueness as a one-of-a-kind species, creating identity threat. First, with rapid advances in robotics, robots' abilities have caught up with or surpassed humans in many areas. We previously mentioned many human employees have been replaced by robots, which is inseparable from robots' capabilities. Some robots far exceed humans in physical tasks, while others outperform humans in intellectual tasks such as mathematics, chess, and Go, undoubtedly threatening humans' sense of identity and uniqueness regarding their own abilities. Second, robots' anthropomorphic appearance is also an important cause of identity threat. Anthropomorphism refers to the tendency or form of attributing uniquely human traits to non-human entities (Epley et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2017). Currently, many robots, especially service robots, have some degree of anthropomorphic appearance, and anthropomorphic service robots are increasingly replacing human employees in numerous service industries (Harris et al., 2018; Yu & Xu, 2020). However, research finds that robots with very high anthropomorphic appearance are perceived not only as realistic threats to human work, safety, and resources but also as threats to human uniqueness, especially when such robots' abilities surpass humans (Yogeeswaran et al., 2016). Moreover, excessively high robot anthropomorphism can also cause the "uncanny valley effect" (Mori, 1970), where within a certain range, humans' liking for robots increases with anthropomorphism, but when anthropomorphism reaches a certain level, humans' liking for robots suddenly falls into a valley, generating disgust and discomfort, which also poses an identity threat to humans.

2.3 Robot Threats Trigger Negative Outcomes Through Compensatory Control

We have detailed the realistic and identity threats robot workers pose to humans, but how do these threats affect workplace objectification? Gaining a sense of control over oneself and the external world is a fundamental human psychological need; people are motivated to believe they control their own lives (Landau et al., 2015), and threats intensify this motivation. The threat orientation model posits that maintaining and strengthening control is one of the main tendencies when people face threats (Thompson & Schlehofer, 2008). Although threats people encounter in life are diverse, lack of perceived control is central to many threat experiences (Greenaway et al., 2014). For example, research finds that sudden threatening events like cancer can easily destroy people's sense of control over their bodies and lives (Leventhal, 1975; Taylor, 1983). Beyond health threats, employment threats are also important factors affecting sense of control (Remondet & Hansson, 1991; Ross & Sastry, 1999). Additionally, threatening community environments (Ross, 2011), terrorism and financial threats (Thompson & Schlehofer, 2008), and even environmental changes (Hornsey et al., 2015; Davydova et al., 2018) all reduce perceived control and strengthen people's motivation to restore control. Since robot workers pose both realistic and identity threats to humans, this project argues that when people perceive these two types of threats from robot workers, they will have a relatively strong motivation to restore control.

According to compensatory control theory (Kay et al., 2008; Kay et al., 2009; Landau et al., 2015), people adopt compensatory strategies to restore perceived control to baseline levels when faced with events and cognitions that reduce perceived control. There are four main strategies for compensating perceived control: strengthening personal agency, supporting external agency (e.g., government, God), affirming specific structure, and affirming nonspecific structure.

The first strategy compensates for perceived control by strengthening personal agency. Personal agency refers to "the belief that one possesses the necessary resources to perform one or a set of behaviors that produce specific outcomes or achieve specific purposes" (Landau et al., 2015). These resources include knowledge, skills, and other abilities that enable the self to take proactive action, exert effort in pursuing goals, and persist in adversity. Therefore, when people face situations with reduced perceived control, they restore perceived control to baseline by strengthening (or self-affirming) their own resources and the likelihood of successfully navigating the environment through personal agency. However, people often harbor illusions about their ability to control random events (Langer, 1975). Using robots as an example, if people adopt the strategy of strengthening personal agency to compensate for perceived control when perceiving robot threats, they may strengthen or self-affirm their resources and abilities to control robots, such as believing they are more capable than robots and can direct robots to do work they arrange.

The second strategy compensates for perceived control by supporting external agency. That is, individuals can rely on systems outside the self, believing these systems can influence outcomes relevant to the individual and increase the likelihood of achieving certain goals. People adopting this strategy relinquish autonomous control over their lives, entrusting personal agency to external systems such as God or government, and restore perceived control through dependence on external systems, believing these systems will mobilize resources to achieve results consistent with their interests. For example, research finds that having participants recall an event where they lacked control increases their belief in God, and this effect only occurs when God is described as intervening in personal daily affairs (Kay et al., 2008). Additionally, Kay et al. (2008) found that reminding participants of events that reduce perceived control leads them to grant more power to their government in subsequent experiments, especially when they hold positive views of the government. Using robots as an example, if people adopt the strategy of supporting external agency to compensate for perceived control when perceiving robot threats, they may increase support for government or strengthen belief in God because they trust the government or God can control robots and protect them.

The third strategy compensates for perceived control by affirming specific cognitive structures. That is, beyond agency, people need to believe that specific actions can reliably produce expected outcomes. It should be noted that this clear, reliable "action-outcome" possibility is specific to the context of reduced perceived control. For example, if a student lacks perceived control over final exams, besides studying hard (strengthening personal agency), they also need to believe that studying hard can reliably predict good final exam results (specific structure) to effectively restore control perception through hard studying. Using robots as an example, if people adopt the strategy of affirming specific cognitive structures to compensate for perceived control when perceiving robot threats, they may believe in some "action-outcome" closely related to robots, such as believing that unplugging the robot (action) will definitely control the robot (outcome).

The fourth strategy compensates for perceived control by affirming nonspecific cognitive structures. Simply put, affirming nonspecific cognitive structures means seeking and preferring simple, clear, and consistent explanations of the world. This strategy differs from the first three: unlike strengthening personal agency, it does not directly target beliefs about one's own resources; unlike supporting external agency, it does not directly target beliefs about external systems; and unlike affirming specific cognitive structures, it targets aspects of social and physical environments outside the specific context of reduced perceived control. The objectification studied in this project is precisely such a simple, clear, and consistent explanation of the external social and physical environment (Landau et al., 2015). People (at least implicitly) know that controlling others requires understanding and influencing others' subjective states, including their personal beliefs and desires. Realizing that others' subjective states are ambiguous, unstable, and often beyond one's influence reduces people's belief that they can control others. Objectification compensates for this lack of perceived control to some extent by simplifying others into objects, making people more confident in their ability to control others. Research finds that when men feel they lack influence over women, they are more inclined to objectify women, and subsequent workplace research also finds that participants guided to doubt their ability to influence colleagues are more inclined to objectify colleagues (Landau et al., 2012). These demonstrate that objectification, as a simple, clear, and consistent explanation of others, helps restore people's reduced perceived control.

With continuous development of robotics technology, large numbers of robot workers have been introduced across industries. These robot workers pose realistic threats such as unemployment by occupying human positions, and identity threats by increasingly approximating humans in appearance and capability. Perceiving these threats will induce people to seek compensatory control and may restore their perceived control to baseline levels through the strategy of affirming nonspecific structures—that is, seeking and preferring simple, clear, and consistent explanations of the world. Workplace objectification is precisely such a simple, clear, and consistent explanation of others in the workplace, because simplifying others into objects often enables people to ignore the complex aspects of others as humans, such as the ambiguity and instability of subjective and internal states, and instead view and treat others simply as objects. In summary, we believe robot workers bring realistic and identity threats to humans, and perceiving these threats makes people seek compensatory control and ultimately objectify others in the workplace to restore perceived control.

2.4 Focusing on Negative Outcomes of Robots in the Workplace Helps Warn of Real-World Problems

This project attempts to study how robot penetration into the workplace threatens workplace professionals psychologically, thereby producing relatively negative interpersonal consequences—workplace objectification—through compensatory control mechanisms. But will robot penetration into the workplace necessarily produce negative outcomes? Of course not. Robots themselves have positive significance in replacing physical labor and assisting decision-making. This project's focus on negative outcomes is mainly because:

First, bad is psychologically stronger than good. Bad is stronger than good (Baumeister et al., 2001), meaning negative events have stronger and more lasting effects on psychological feelings than positive events. Winning the lottery brings joy, but winners' happiness quickly returns to pre-winning levels. In contrast, relative to the brief joy from positive events, people disabled in accidents recover psychologically much more slowly (Brickman et al., 1978), even though many eventually recover (Taylor, 1983). Similarly, the pain of losing some money is much greater than the joy or happiness from gaining the same amount (Kahneman & Tversky, 1984). Since bad is stronger than good and negative events have more lasting and stronger impacts on people, our attention to and understanding of negative events becomes particularly important. Workplace objectification involves viewing others in the workplace as objects, which is inherently a degradation and insult to humanity, and it further brings negative consequences such as self-objectification (e.g., Loughnan et al., 2017) and negative psychological and occupational health outcomes (Caesens et al., 2017), compounding negative impacts. Therefore, in this project, we focus on the negative outcomes that robots may produce in the workplace—workplace objectification—and exploring this negative outcome in the current social context helps us better provide early warnings.

Second, the positive impact of robots on interpersonal relationships remains debatable. Although many researchers hold negative views on robots' impact on interpersonal relationships and have obtained empirical evidence—for example, robots increase people's material insecurity, causing them to perceive greater threat from immigrants and foreign workers, thereby increasing support for anti-immigration policies (e.g., Frey et al., 2018; Im et al., 2019)—some research has also found potential positive effects of robots on interpersonal relationships. Recent research found that robot workers as an outgroup can increase people's panhumanism, highlighting a common human identity and thereby reducing prejudice against human outgroups (Jackson et al., 2020). However, Jackson et al. (2020) also noted in their discussion that data they collected from 37 countries showed that countries with the fastest automation over the past 42 years also showed increased explicit prejudice against outgroups, an effect partially related to rising unemployment (Jackson et al., 2020). They also stated in their discussion that their study did not examine robot threats, suggested that robot threats might not reduce interpersonal prejudice, and encouraged future research to focus on how robot threats affect interpersonal relationships. In summary, although a small amount of research has obtained some positive results, the positive impact of robots on interpersonal relationships remains debatable. Therefore, this project further examines the negative interpersonal outcomes that robots may produce, focusing particularly on threats robots pose to humans.

Through this project's research, we strive to identify the threatening consequences of the new phenomenon of increasingly numerous AI, particularly robots, appearing in the workplace, prospectively understand its principles, mechanisms, and possible solutions, and prepare for and provide possible references for future workplace problems.

3. Research Framework

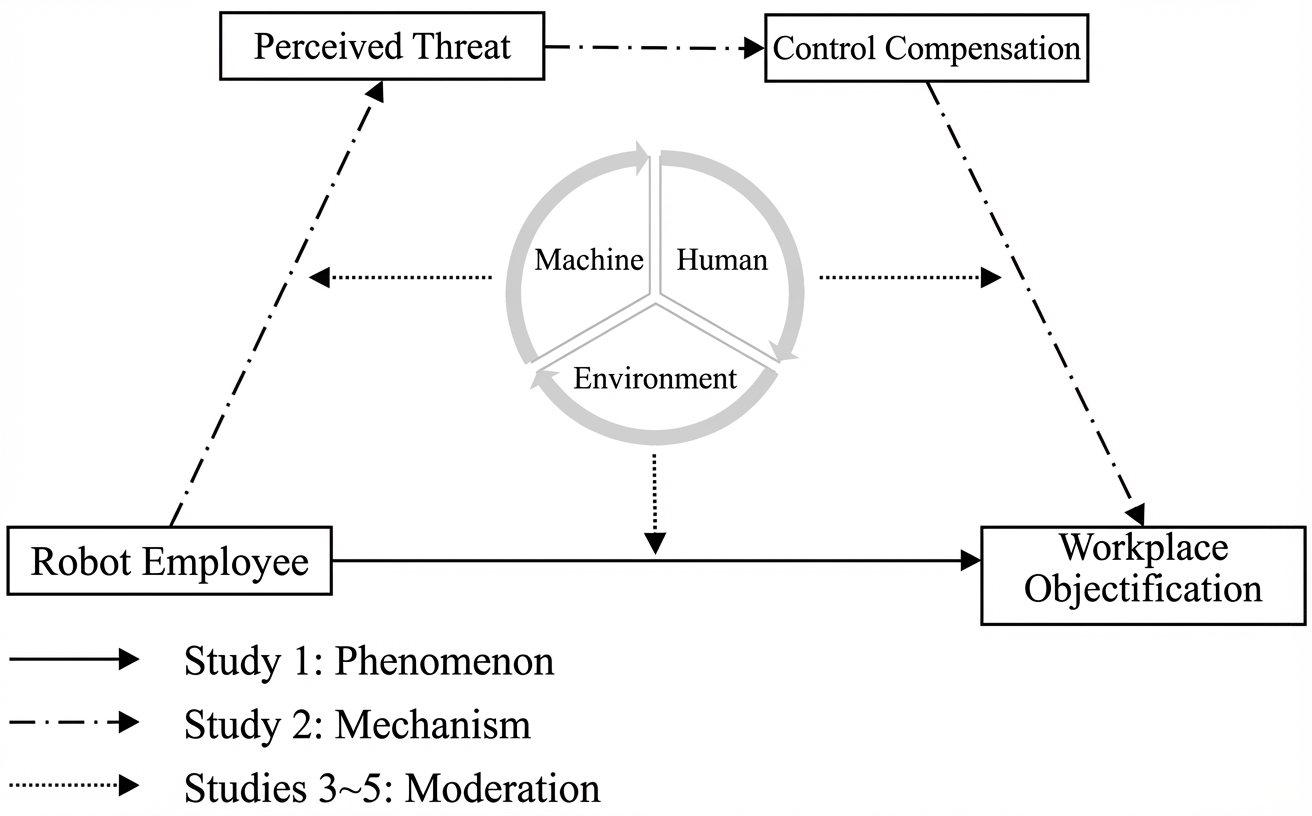

This project's research content is shown in Figure 2, specifically divided into five studies that respectively explore the existence of robots' influence on workplace objectification, mediating mechanisms, and moderating mechanisms from three aspects: person, machine, and environment. This project first verifies that robot worker salience affects workplace objectification; then explores the mediating mechanisms of robot influence on workplace objectification, attempting to identify the chain mediating effect of perceived threat and compensatory control; next, it examines moderating effects on robot influence on workplace objectification from personal, robot, and environmental perspectives, and explores intervention strategies for workplace objectification from an organizational culture perspective. Specifically, Study 1 verifies the existence and direction of robot influence on workplace objectification; Study 2 explores the chain mediating effect of perceived threat and compensatory control; Study 3 examines personal factors' moderating effects, including strengthening personal agency, supporting external agency, and affirming specific cognitive structures; Study 4 examines robot factors' moderating effects, including anthropomorphism and mind perception of agency and experience; Study 5 examines environmental factors' moderating effects, including different organizational culture orientations and ethical organizational culture, and thereby explores intervention strategies for workplace objectification.

Figure 2. Project Research Framework Diagram

3.1 Study 1: The Existence of Robot Influence on Workplace Objectification

As robotics technology continues to develop, increasing numbers of robots have entered human workplaces, undertaking large amounts of work originally performed by humans. Early robots could only perform simple, repetitive industrial labor due to limited intelligence, but today's technological advances are opening new prospects, with large numbers of robots beginning to enter previously human-exclusive work domains such as healthcare (e.g., Agnihotri & Gaur, 2016), services (e.g., Persado, 2017), military (e.g., Lin et al., 2008), education (e.g., Leyzberg et al., 2014; Ritschel, 2018), law (e.g., Xu & Wang, 2019), corporate recruitment (e.g., Nawaz, 2019), and even management positions with higher cognitive demands (e.g., Dixon et al., 2021). Numerous social surveys indicate people have concerns about robot development (e.g., Smith & Anderson, 2017). Robots seizing human jobs will inevitably increase human unemployment, thereby increasing risks of social unrest and imbalance (e.g., Borenstein, 2011; McClure, 2018). It can be said that humans have already perceived robot threats, which manifest not only in realistic aspects such as employment and safety but also in threats to human identity and uniqueness. Such threats obviously lead to negative attitudes toward robots (Yogeeswaran et al., 2016), but what impact do they have on interpersonal relationships?

Answers to this question remain controversial. Because robots' occupation of jobs intensifies competition between people, substantial research suggests robot threats negatively affect interpersonal relationships. For example, research finds that threats from robots and other automation to future employment increase people's material insecurity, causing them to perceive greater threat from immigrants and foreign workers, thereby increasing support for anti-immigration policies (Frey et al., 2018; Im et al., 2019). However, recent research found that increased robot workers help reduce interpersonal prejudice because robots increase people's panhumanism, highlighting a common human identity and thereby reducing prejudice against outgroups (Jackson et al., 2020). But this study avoided examining robot threats to humans, and the researchers themselves noted that data they collected from 37 countries showed that countries with the fastest automation over the past 42 years also showed increased explicit prejudice against outgroups, an effect partially related to rising unemployment, indicating their study's limitations (Jackson et al., 2020). Therefore, what impact robots will have on interpersonal relationships remains an unresolved and ongoing question.

Based on this, we propose the first question this project explores: What impact will robots have on interpersonal relationships? And combining the current situation of numerous robots appearing in workplace environments and the current state and research significance of workplace objectification, we focus our research on robots' impact on workplace objectification and propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Robot worker salience will increase workplace objectification.

3.2 Study 2: The Mediating Mechanism of Robot Influence on Workplace Objectification

In Study 1, we repeatedly verified robots' influence on workplace objectification through multiple research methods. What are the underlying mechanisms of this influence? Through what pathways does robot worker salience cause increased workplace objectification? In Study 2, we will focus on exploring the mediating mechanisms through which robots increase workplace objectification.

As robot worker ranks continue to grow, increasing numbers of human positions have been occupied by robots, and this trend continues to expand with AI development. In many work domains, robots' efficiency and costs are already far superior to humans, undoubtedly posing realistic threats to humans regarding work and resources. Moreover, as robotics technology advances, robots increasingly approximate humans in both appearance and capability, threatening humans' sense of identity and uniqueness as a one-of-a-kind species, thereby causing identity threat. Therefore, robot worker salience may pose realistic and identity threats to people. When facing threats, maintaining and strengthening control is one of people's main tendencies (Thompson & Schlehofer, 2008). Thus, when humans perceive threats from robot workers, they also develop relatively strong motivation to restore control. According to compensatory control theory (Kay et al., 2008; Kay et al., 2009; Landau et al., 2015), people adopt compensatory strategies to restore perceived control to baseline levels when faced with events and cognitions that reduce perceived control. One such strategy is to compensate for perceived control by affirming nonspecific cognitive structures—that is, seeking and preferring simple, clear, and consistent explanations of the world. Objectification is precisely a manifestation of this compensatory control strategy, because simplifying others into objects often enables people to ignore the complex aspects of others as humans, such as the ambiguity and instability of subjective and internal states, and instead view and treat others simply as objects. Therefore, objectification is precisely such a simple, clear, and consistent explanation of others that helps restore people's reduced perceived control (Landau et al., 2015). Previous research also shows that reduced perceived control leads men to objectify women more, and this effect also exists in workplace contexts (Landau et al., 2012).

In summary, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: In the effect of robots on workplace objectification, there exists a chain mediating relationship among robot worker salience, perceived threat, compensatory control, and workplace objectification. Specifically, robot worker salience increases people's perceived threat from robots, which triggers compensatory control, ultimately leading to more workplace objectification.

3.3 Study 3: Personal Factors as Moderators of Robot Influence on Workplace Objectification

When encountering threats, people develop relatively strong motivation to restore control. According to compensatory control theory (Kay et al., 2008; Kay et al., 2009; Landau et al., 2015), people adopt compensatory strategies to restore their perceived control to normal levels. Compensatory control theory proposes four main compensatory control strategies: The first is strengthening personal agency to compensate for perceived control—that is, strengthening (or self-affirming) one's own resources and the likelihood of successfully navigating the environment through personal agency to restore perceived control to baseline. The second is supporting external agency to compensate for perceived control—that is, entrusting personal agency to external systems such as God or government, and restoring perceived control through dependence on external systems, believing these systems will mobilize resources to achieve results consistent with one's interests. The third is affirming specific cognitive structures to compensate for perceived control—that is, believing that specific actions can reliably produce expected outcomes, with this clear, reliable "action-outcome" possibility being specific to the context of reduced perceived control. The fourth is affirming nonspecific cognitive structures to compensate for perceived control—that is, seeking and preferring simple, clear, and consistent explanations of the world.

So when facing realistic and identity threats that robots may pose, which strategy will people consciously or unconsciously choose to restore personal control? The selection and preference among the four strategies of compensatory control theory currently remain unresolved (Landau et al., 2015). As mentioned earlier, the objectification studied in this project belongs to the fourth compensatory control strategy—affirming nonspecific cognitive structures to compensate for perceived control, seeking and preferring simple, clear, and consistent explanations of the world. However, reduced perceived control does not necessarily point to people's affirmation of nonspecific structures; personal and environmental factors related to other compensatory control strategies may also moderate this effect (e.g., Cutright, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2010), because people have the opportunity to choose other compensatory control strategies to restore perceived control. Therefore, in this study, we consider personal factors that may moderate robots' effect on increasing workplace objectification, and from the other three strategies of compensatory control theory and other forms of affirming nonspecific cognitive structures, we respectively explore whether related personal factors can moderate robots' effect on increasing workplace objectification.

In summary, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: Personal agency can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, when personal agency is weak, robot worker salience will significantly increase workplace objectification; when personal agency is strong, robot worker salience will not significantly affect workplace objectification.

Hypothesis 3b: External agency can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, when support for external agency is weak, robot worker salience will significantly increase workplace objectification; when support for external agency is strong, robot worker salience will not significantly affect workplace objectification.

Hypothesis 3c: Specific cognitive structures can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, when belief in specific cognitive structures is weak, robot worker salience will significantly increase workplace objectification; when belief in specific cognitive structures is strong, robot worker salience will not significantly affect workplace objectification.

Hypothesis 3d: Other forms of nonspecific cognitive structures can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, when people can engage in compensatory control through other forms of affirming nonspecific cognitive structures (such as perceiving clear workplace hierarchies), the effect of robot worker salience on workplace objectification will be weakened.

3.4 Study 4: Robot Factors as Moderators of Robot Influence on Workplace Objectification

In human-robot interaction, besides personal factors, robot factors constitute another important variable. We consider robot factors from both internal and external aspects: robot appearance anthropomorphism and people's mind perception of robots. Anthropomorphism refers to the tendency or form of attributing uniquely human traits to non-human entities (Epley et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2017). With rapid technological development, AI robots have become a popular domain for anthropomorphism applications. Research finds that robots with very high appearance anthropomorphism are perceived not only as realistic threats to human work, safety, and resources but also as threats to human uniqueness, especially when such robots' abilities surpass humans (Yogeeswaran et al., 2016). Moreover, when robot appearance anthropomorphism reaches a certain level, it may trigger the uncanny valley effect, which also poses perceived threats to humans. Therefore, we believe robot appearance anthropomorphism increases identity threat robots pose to people, thereby aggravating robots' effect on workplace objectification.

After anthropomorphism, robots are viewed as having minds. Mind perception theory (Gray et al., 2007) posits that people perceive the minds of all things in the world along two dimensions: agency (i.e., capacity for self-control, moral behavior, planning, etc.) and experience (i.e., capacity to experience desires, fears, pleasure, etc.). Robots are generally perceived as having moderate agency and low experience (Gray et al., 2007), and perceptions of robots' agency and experience also affect people's perception of robot threats. Because increased perceived agency and perceived experience in robots makes them more similar to humans, thereby causing stronger identity threat to humans. Therefore, we believe mind perception of robots—that is, perceiving robots as having varying degrees of agency and experience—also moderates robots' effect on increasing workplace objectification.

In summary, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4a: Robot appearance anthropomorphism can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, when robot appearance anthropomorphism is high, robot worker salience will significantly increase workplace objectification; when robot appearance anthropomorphism is low, robot worker salience will not significantly affect workplace objectification.

Hypothesis 4b: Perceived robot agency can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, when perceived robot agency is high, robot worker salience will significantly increase workplace objectification; when perceived robot agency is low, robot worker salience will not significantly affect workplace objectification.

Hypothesis 4c: Perceived robot experience can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, when perceived robot experience is high, robot worker salience will significantly increase workplace objectification; when perceived robot experience is low, robot worker salience will not significantly affect workplace objectification.

3.5 Study 5: Environmental Factors as Moderators of Robot Influence on Workplace Objectification

Besides human factors and robot factors, environmental factors cannot be ignored. Moreover, environmental factors are important components that organizations can improve from within, thus serving as effective and feasible intervention methods. Previous research found that organizational culture correlates to some degree with workplace objectification (Auzoult & Personnaz, 2016). Therefore, this study examines organizational culture as a potential moderating variable for robots' effect on workplace objectification.

The first organizational culture classification we examine is based on Quinn's (1988) model, which divides organizational culture into four dimensions: support—encouraging participation, cooperation, trust, and verbal and informal communication; innovation—seeking creativity and encouraging employees to embrace change and participation; rules—emphasizing respect for authority, procedural rationality, and division of labor, with written formal communication; and goals—an orientation focusing on performance indicators, responsibility, and achievement. These four cultures reflect how organizational members interpret and make sense of their work environment. Objectification is a means of reducing complexity and uncertainty to restore control (Landau et al., 2012), while strong organizational culture can reduce complexity and uncertainty by providing certain interpretive frameworks and values, making organizational members' behavior predictable; thus workplace objectification is closely related to organizational culture. Previous research found that goal-oriented and support-oriented organizational cultures can reduce workplace objectification (of others), innovation-oriented organizational culture can reduce workers' self-objectification, while rules-oriented organizational culture aggravates workers' self-objectification (Auzoult & Personnaz, 2016). However, how innovation- and rules-oriented organizational cultures moderate objectification of others remains unclear. Workplace objectification is closely related to power; research finds that power status changes how people cognize others: compared with low-power-status and control-group participants, high-power-status participants objectify subordinates more, evaluating subordinates from a usefulness perspective and interacting with subordinates entirely based on their usefulness for achieving goals rather than their values and human qualities (Gruenfeld et al., 2008). From an organizational perspective, emphasizing power and control manifests as rules-oriented organizational culture; therefore, we believe rules-oriented organizational culture may aggravate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Innovation, while a strong driver of individual, organizational, and even societal development, is also associated with unethical behavior in organizations. Previous research found that innovation increases individuals' motivation to think outside the box, which in turn leads to unethical behavior, and simply priming participants with innovation-related cognition produces this negative consequence (Gino & Ariely, 2012). That is, innovation-oriented organizational culture may also foster more unethical behavior. Combined with this project's research topic, robots are clearly representatives of innovation; organizations with robot workers mostly also have innovation-oriented organizational culture, while workplace objectification is undoubtedly an unethical cognition and behavior. Therefore, we believe innovation-oriented organizational culture may aggravate robots' effect on workplace objectification.

The second type of organizational culture is ethical organizational culture. Ethical organizational culture can support people in making good moral decisions and complying with moral norms (Trevino & Nelson, 2021). Many factors in organizations may foster unethical behavior, but when ethical organizational culture creates a good moral atmosphere, the possibility of moral deviance is greatly reduced. Ethical organizational culture is both formal and informal, manifested through cultural messages and reward-punishment systems (Trevino & Brown, 2004), and has been found to significantly correlate with more organizational citizenship behavior (i.e., employees' voluntary supportive behavior toward the organization), less slacking, and better job performance (Peng & Kim, 2020). Workplace objectification, as an unethical cognition and behavior in organizations, may be influenced by ethical organizational culture. Therefore, we believe ethical organizational culture may moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification.

In summary, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5a: Different organizational culture orientations can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, under innovation- and rules-oriented organizational cultures, robot worker salience will significantly increase workplace objectification; under support- and goal-oriented organizational cultures, robot worker salience will not significantly affect workplace objectification.

Hypothesis 5b: Ethical organizational culture can moderate robots' effect on workplace objectification. Specifically, when ethical organizational culture is weak, robot worker salience will significantly increase workplace objectification; when ethical organizational culture is strong, robot worker salience will not significantly affect workplace objectification.

4. Theoretical Construction and Innovation

As robots are increasingly used in the workplace, research is urgently needed on what psychological and behavioral reactions they bring to workplace employees and what impacts they have on social interactions between leaders and employees and among employees themselves. It should be noted that AI products have long entered human life, but some appear as algorithms that are formless and shapeless; workplace office algorithms are often not given much attention. But robots are different, especially anthropomorphic robots—they prompt people to reflect on themselves or human-object relationships beyond novelty. In the long run, robots will inevitably become normal in human life, yet psychological theoretical preparation for robots penetrating human life and even the workplace is actually insufficient, or rather, few complete theories explain how humans psychologically and behaviorally respond when robots participate in human activities (Yu & Xu, 2018).

Indeed, some so-called "theories" explore this content. For example, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Davis, 1989) borrows from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) to explain human acceptance of technology through perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Such simple theories can propose some obvious dimensions and measurements, but they are not top-down theoretical constructions formed by rational reasoning; rather, they more often result from bottom-up identification of potentially related small variables directly from superficial dimensions of cognition, emotion, and behavior to weave "stories" and form "theories." Intuitively, this creates theories with poor theoretical feel, weak depth of thinking, and difficulty in outlining deep psychological changes in humans. Influenced by this, some so-called "theories" even directly violently integrate variables—for example, Venkatesh et al.'s (2003) Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) directly measures all dimensions proposed by eight previously conceivable theories, uses technology acceptance as the dependent variable for regression, and retains significant variables. Such practices are essentially simple regression with variable hodgepodge and far from being called theories (Xu & Yu, 2020).

Designating dependent variables as "acceptance," "purchase," "liking," and other attitudes, behaviors, or behavioral intentions is relatively easy, but explaining the processes therein is relatively difficult. Such theories may perhaps be considered from the perspective of robots playing different roles in human life, but of course, such thinking may only be explained by traditional psychological theories. If robots penetrate human work and life, their roles may be at least two: bystander and participant. If robots are bystanders in work, they may serve as a kind of other-person presence effect when humans perform social behaviors, because they are not necessarily perceived as "people," so this other-person presence effect will correspondingly weaken (Raveendhran & Fast, 2019). In other words, due to robots' existence and their being less perceived as real people in perception, the social evaluation and resulting evaluation anxiety people experience will decrease, causing people to possibly more readily accept the use of robots in the workplace or AI products in a broad sense (Raveendhran & Fast, 2019). This is actually exploitable—it causes humans to broadly lower their guard against workplace robots and reduce perception of their hostile intentions. If it is not in robot form but some AI program, this effect will be stronger. For example, research finds that employees are more likely to accept algorithm-controlled workplace behavior data monitoring and tracking (such as wearing wearable devices to collect personal information at work), while tending to reject similar data tracking controlled by humans, precisely because such AI products are perceived as less evaluative of people, having less will and less autonomy (Raveendhran & Fast, 2021).

But workplace robots will probably not merely be bystanders; they must have the possibility of participation. Because workplace AI products and robots are not so-called "strong AI" in the current state, they often produce problems when interacting with people, creating specific experiences for humans interacting with robots in the workplace (Puntoni et al., 2021). These experiences may include feelings of exploitation due to unknown working principles of workplace robots and algorithms (i.e., opacity), feelings of being misunderstood due to errors produced by workplace robots and algorithms, or feelings of alienation due to social interaction (Puntoni et al., 2021). And regardless of what human-robot interaction experience, the subsequent psychological process seems consistent—that is, feeling deprived of or reduced in sense of control. In fact, seeking mastery and acquiring sense of control itself is an important motivational source for humans seeking meaning and an essential need for human motivational cognition (Kruglanski et al., 2021; Jost et al., 2003). This is consistent with the control compensation psychological process discussed in this project, except that this project does not directly explore experiences but focuses on threat and social identity processes.

In fact, this project has been exploring what it means to be human—that is, human identity as human. Workplace objectification originates from social phenomena; the popularity of terms like "tool person" and "corporate livestock" amplifies workplace objectification. Such statements involving "distinctions between humans and animals" already implicitly suggest differences between humans and non-humans. Treating humans as non-humans and treating non-humans as humans both cause human anxiety about and even threats to human identity (Yu, 2020). Especially robots, as existences between machine and human, also cause humans to make subtle considerations about human identity. This project first clarifies that the objectification concept originates from "distinctions between humans and objects" rather than the narrower concept of sexual objectification, focuses on workplace objectification, and examines robots' impact on workplace objectification against the AI development background. This project's exploration of robot influence also starts from "distinctions between humans and machines," examining the control compensation process following identity threat—that is, the compensatory control strategy of affirming nonspecific cognitive structures to restore control levels, exploring the possibility of workplace objectification as such a strategy for compensatory control of robot threats. Through this project's exploration, these human-nonhuman processes can form some specific theory of how humans perceive social things—that is, perceiving society with humans at the center, with all social entities on an existence chain with humans at the midpoint (Brandt & Reyna, 2011). That is, how humans understand the world depends to some extent on how humans understand humans themselves. Understanding and comprehending the world requires a framework, a model, a kind of knowledge, and these frameworks, models, and knowledge are based on the past. For never-before-seen fresh things, we must necessarily analogize, simulate, and apply according to previously existing things. Human identity itself is this most basic schema and knowledge, or subject knowledge (Epley et al., 2007). This project's completion will help understand the possibility of existence chain theory with subject identity at its core from two directions—animal and machine (Haslam, 2006)—based on the "human-machine distinction" triggered by workplace robots and the subsequent psychological processes that result in workplace objectification outcomes from the "human-animal distinction," and based on this possibility generate a unique mid-range theory of psychology for robots penetrating human life.

Of course, this project also has practicality. Based on current AI development prospects, it raises questions from workplace social phenomena and era backgrounds, combines social psychology theories to explore robots' impact on workplace objectification, and simultaneously starts from the weak points of objectification research to study workplace objectification phenomena. It combines intergroup threat theory and compensatory control theory to propose potential mediating mechanisms of robot influence on workplace objectification. This can prospectively explore different variables moderating robots' effect on workplace objectification from three aspects—person, machine, and environment—such as personal agency, anthropomorphism, and organizational culture, consider possible solutions to workplace objectification, and intend to frontier-explore its workplace consequences, especially negative effects, and propose possible countermeasures.

References

Jiang, Y., & Chen, H. (2019). Attentional and memory bias toward body cues among women with self-objectification. Psychological Science, 42(6), 1462–1469.

Sun, Q., Zheng, L., & Zheng, Y. (2013). Sexual objectification and women's self-objectification. Advances in Psychological Science, 21(10), 1794–1802.

Weber, M. (2010). The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. Guangxi Normal University Press.

Xu, L., & Yu, F. (2020). Factors influencing robot acceptance. Chinese Science Bulletin, 65(6), 496–510.

Xu, L., Yu, F., Wu, J., Han, T., & Zhao, L. (2017). Anthropomorphism: From "it" to "he". Advances in Psychological Science, 25(11), 1942–1954.

Yang, W., Jin, S., He, S., Zhang, X., & Fan, Q. (2015). Dehumanization research: Theoretical comparison and application. Advances in Psychological Science, 23(7), 1246–1257.

Yu, F., Peng, K., & Zheng, X. (2015). Psychology in the big data era: Reconstruction and characteristics of China's psychological discipline system. Chinese Science Bulletin, 60, 520–525.

Yu, F., & Xu, L. (2018). How to create moral AI? A psychological perspective. Global Media Journal, 5(4), 24–42.

Yu, F., & Xu, L. (2020). Anthropomorphism of artificial intelligence. Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Sciences), 57(5), 52–60.

Yu, F. (2020). On artificial intelligence and being human. People's Tribune·Academic Frontier, 2020(01), 30–36.

Zheng, P., Lv, Z., & Jackson, T. (2015). Effects of self-objectification on women's mental health and its mechanisms. Advances in Psychological Science, 23(1), 93–103.

Zhou, H., & Long, L. (2004). Statistical tests and control methods for common method bias. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942–950.

Abril, D. (2019). A.I. might be the reason you didn't get the job. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://fortune.com/2019/12/11/mpw-nextgen-ai-hr-hiring-retention

Agnihotri, R., & Gaur, S. (2016). Robotics: A new paradigm in geriatric healthcare. Gerontechnology, 15(3), 146–155.

Amodio, D. M., Devine, P. G., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2008). Individual differences in the regulation of intergroup bias: The role of conflict monitoring and neural signals for control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 60–74.

Anderson, C., John, O. P., & Keltner, D. (2012). The personal sense of power. Journal of Personality, 80(2), 313–344.

Andrighetto, L., Baldissarri, C., & Volpato, C. (2017). (Still) modern times: Objectification at work. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(1), 25–35.

Andrighetto, L., Baldissarri, C., Gabbiadini, A., Sacino, A., Valtorta, R. R., & Volpato, C. (2018). Objectified conformity: Working self-objectification increases conforming behavior. Social Influence, 13(2), 78–90.

Auzoult, L., & Personnaz, B. (2016). The role of organizational culture and self-consciousness in self-objectification in the workplace. TPM: Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 23(3), 271–284.

Baldissarri, C., Andrighetto, L., & Volpato, C. (2014). When work does not ennoble man: Psychological consequences of working objectification. TPM: Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 21(3), 1–13.

Baldissarri, C., Andrighetto, L., Di Bernardo, G. A., & Annoni, A. (2020). Workers' self-objectification and tendencies to conform to others. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 30(5), 1–14.

Baldissarri, C., Valtorta, R. R., Andrighetto, L., & Volpato, C. (2017). Workers as objects: The nature of working objectification and the role of perceived alienation. TPM – Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 24, 153–166.

Bartky, S. L. (1990). Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. New York: Routledge.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Belmi, P., & Schroeder, J. (2021). Human "resources"? Objectification at work. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(2), 384–417.

Borenstein, J. (2011). Robots and the changing workforce. AI & Society, 26(1), 87–93.

Brandt, M. J., & Reyna, C. (2011). The chain of being: A hierarchy of morality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(5), 428–446.

Brian, H. (2017). Pepper the robot gets a gig at the Oakland airport. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://techcrunch.com/2017/01/25/pepper-robot

Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(8), 917–927.

Caesens, G., Stinglhamber, F., Demoulin, S., & De Wilde, M. (2017). Perceived organizational support and employees' well-being: The mediating role of organizational dehumanization. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(4), 527–540.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Polli, F., & Dattner, B. (2019). Building ethical AI for talent management. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://hbr.org/2019/11/building-ethical-ai-for-talent-management

Changi Journeys. (2019). Wine-picking robot helps out at Changi's DFS. Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://osf.io/dfrks/

Cutright, K. M. (2012). The beauty of boundaries: When and why we seek structure in consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(5), 775–790.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Davydova, J., Pearson, A. R., Ballew, M. T., & Schuldt, J. P. (2018). Illuminating the link between perceived threat and control over climate change: The role of attributions for causation and mitigation. Climatic Change, 148(1–2), 45–59.

Dixon, J., Hong, B., & Wu, L. (2021). The robot revolution: Managerial and employment consequences for firms. Management Science, 67(9), 5586–5605.

Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological Review, 114(4), 864–886.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, UK: Addison-Wesley.

Frank, T. (2016). How is Pepper, softbank's emotional robot, doing? Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.therobotreport.com/how-is-pepper-softbanks-emotional-robot-doing

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women's lived experience and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206.

Freeman, J. B., & Ambady, N. (2010). MouseTracker: Software for studying real-time mental processing using a computer mouse-tracking method. Behavior Research Methods, 42, 226–241.

Frey, C. B., Berger, T., & Chen, C. (2018). Political machinery: Did robots swing the 2016 U.S. presidential election? Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34(3), 418–442.

Gino, F., & Ariely, D. (2012). The dark side of creativity: Original thinkers can be more dishonest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 445–459.

Gray, H. M., Gray, K., & Wegner, D. M. (2007). Dimensions of mind perception. Science, 315, 619.

Gray, K., Knobe, J., Sheskin, M., Bloom, P., & Barrett, L. F. (2011). More than a body: Mind perception and the nature of objectification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 1207–1220.

Greenaway, K. H., Louis, W. R., Hornsey, M. J., & Jones, J. M. (2014). Perceived control qualifies the effects of threat on prejudice. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(3), 422–442.

Greenwald, A. G., & Farnham, S. D. (2000). Using the implicit association test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 1022–1038.

Grimmelikhuijsen, S., & Knies, E. (2017). Validating a scale for citizen trust in government organizations. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(3), 583–601.

Gruenfeld, D. H., Inesi, M. E., Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Power and the objectification of social targets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 111–127.

Gwinn, J. D., Judd, C. M., & Park, B. (2013). Less power = less human? Effects of power differentials on dehumanization. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 464–470.

Harris, K., Kimson, A., & Schwedel, A. (2018). Why the automation boom could be followed by a bust. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2018/03/why-the-automation-boom-could-be-followed-by-a-bust

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264.

Heath, P., & Schneewind, J. B. (1997). Lectures on ethics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hendricks, B., Marvel, M. K., & Barrington, B. L. (1990). The dimensions of psychological research. Teaching of Psychology, 17(2), 76–82.

Hewstone, M. H., Rubin, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup bias. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 575–604.