Abstract

The volume of candidate diagnostic images generated by FAST pulsar searches is increasing exponentially, posing significant challenges to scientific data management and necessitating urgent research into compression methods to enable efficient storage and accelerated network transmission and sharing of these diagnostic images. Pulsar diagnostic images comprise sparse black-and-white images, randomly distributed grayscale images, and color images; thus, treating them uniformly as color images and applying a single compression method is evidently inappropriate. This study proposes a partitioned compression scheme for pulsar candidate diagnostic images utilizing White Block Skipping (WBS) coding and deep network compression coding models. The proposed method is trained and validated using pulsar candidate diagnostic images from recent FAST sky survey search projects. Experimental results demonstrate that the improved WBS compression achieves performance five times superior to PNG for sparse black-and-white images; the deep network compression algorithm exhibits PSNR performance superior to JPEG and JPEG2000, comparable to BPG, for grayscale and color images, while its SSIM performance substantially surpasses traditional compression algorithms.

Full Text

Research on Compression of Pulsar Candidate Diagnostic Images Based on White Block Skipping Coding and Deep Neural Networks

Jiatao Jiang¹,²,³, Xiaoyao Xie¹,³, Xuhong Yu¹,³

¹Guizhou Key Laboratory of Information and Computing Science, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang 550001, China

²School of Mathematical Sciences, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang 550001, China

³FAST Early Science Data Center, Guiyang 550001, China

Abstract

The volume of candidate diagnostic images generated by FAST pulsar searches has grown exponentially, posing significant challenges for scientific data management. Effective compression methods are urgently needed to enable efficient storage and accelerate network transmission and sharing of these diagnostic images. Pulsar diagnostic images comprise sparse binary images, randomly distributed grayscale images, and color images, making it unreasonable to treat them uniformly as color images and compress them with a single method. This paper proposes a partitioned compression approach combining white block skipping (WBS) coding with deep neural network compression models. Using pulsar candidate diagnostic images from recent FAST sky survey projects for training and validation, our results demonstrate that the improved WBS compression achieves five times better performance than PNG for sparse binary images. For grayscale and color images, the deep network compression algorithm exhibits superior PSNR performance compared to JPEG and JPEG2000, comparable to BPG, and far exceeds traditional compression algorithms in SSIM performance.

Keywords: Pulsar candidate diagnostic image compression; Deep network compression model; White block skipping coding; Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST)

1 Introduction

Since the completion of the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST) in Guizhou, China in September 2016, pulsar search has been one of its key scientific programs. To date, the FAST Early Science Data Center has computationally identified 240 new pulsar candidates, with 123 confirmed as new pulsars. Notable discoveries include J1859-0131 and J1931-01, the first pulsars discovered by Chinese radio telescopes, and J0318+0253, the first millisecond pulsar found by FAST and one of the faintest radio-loud high-energy millisecond pulsars discovered to date. These achievements demonstrate FAST's potential to make substantial contributions to international low-frequency gravitational wave detection.

Sky survey observation data undergo computational processing to generate massive quantities of pulsar candidate diagnostic images. For example, processing 2,000 data files daily produces 300,000 images requiring 20 GB of storage space. This exponential growth in diagnostic image volume presents formidable challenges for scientific data management. These diagnostic images constitute critical scientific data for astronomers to inspect survey data and identify pulsars, serving as the foundation for exploring new search techniques and representing important resources for astronomical research, education, and open sharing. In daily operations, pulsar identification software continuously transmits these images over dedicated networks; scientists explore new research methods based on them, such as the PICS method proposed by Zhu et al.; and the FAST cloud platform publishes extensive shared information containing numerous pulsar candidate diagnostic images. Consequently, research on compression technologies to enable effective storage and accelerate network transmission sharing is urgently necessary.

Traditional mainstream image compression standards such as JPEG, JPEG2000, and BPG employ transform coding. JPEG applies block-based DCT transformation, converting image information from the spatial domain to the DCT domain where coefficient energy is relatively concentrated, followed by quantization and entropy coding. JPEG2000 utilizes discrete wavelet transform (DWT) with hierarchical entropy coding. However, DCT and DWT are fixed linear transform functions—essentially convolution operations with handcrafted convolution kernels—which may not be optimal for decorrelating pulsar image data. In recent years, neural network-based image compression methods have gained increasing attention from researchers. Toderici et al. proposed an RNN-based image coding framework, while Balle et al. introduced a convolutional neural network-based compression architecture that learns an entropy model for the distribution of bottleneck layer representations, better removing internal image redundancy. Neural network-based image compression leverages large image datasets for optimization, proving more effective than handcrafted compression modules for decorrelation and compact transformation. However, existing compression methods target natural images without fully considering the distinct characteristics of pulsar diagnostic images. Since pulsar diagnostic images consist of sparse binary images, randomly distributed grayscale images, and color images, treating them uniformly with a single transform compression algorithm is clearly unreasonable.

To address these characteristics, we propose a compression method combining white block skipping coding with deep network image compression models. For binary images containing curves and text in diagnostic images, we first binarize the image and then apply an improved adaptive hierarchical block-skipping algorithm. For the deep neural network compression model design, we employ a convolutional neural network autoencoder structure comprising a forward encoding network, quantizer, entropy coder, and inverse decoding network. Using the weighted sum of quantization feature coding rate and distortion error as the loss function, we adaptively learn each module function from large quantities of pulsar candidate diagnostic images via SGD optimization. To enable effective arithmetic coding, we use a network-learned nonlinear function to approximate the actual data distribution model of the latent representation features. Experimental results using pulsar candidate diagnostic images from recent FAST sky survey projects demonstrate that our deep network compression algorithm (DNCM) achieves PSNR values superior to JPEG and comparable to JPEG2000, while SSIM values far exceed traditional compression algorithms. Particularly at low bit rates, the high SSIM values of reconstructed images ensure superior visual quality, proving the effectiveness of our algorithm for pulsar candidate diagnostic image compression.

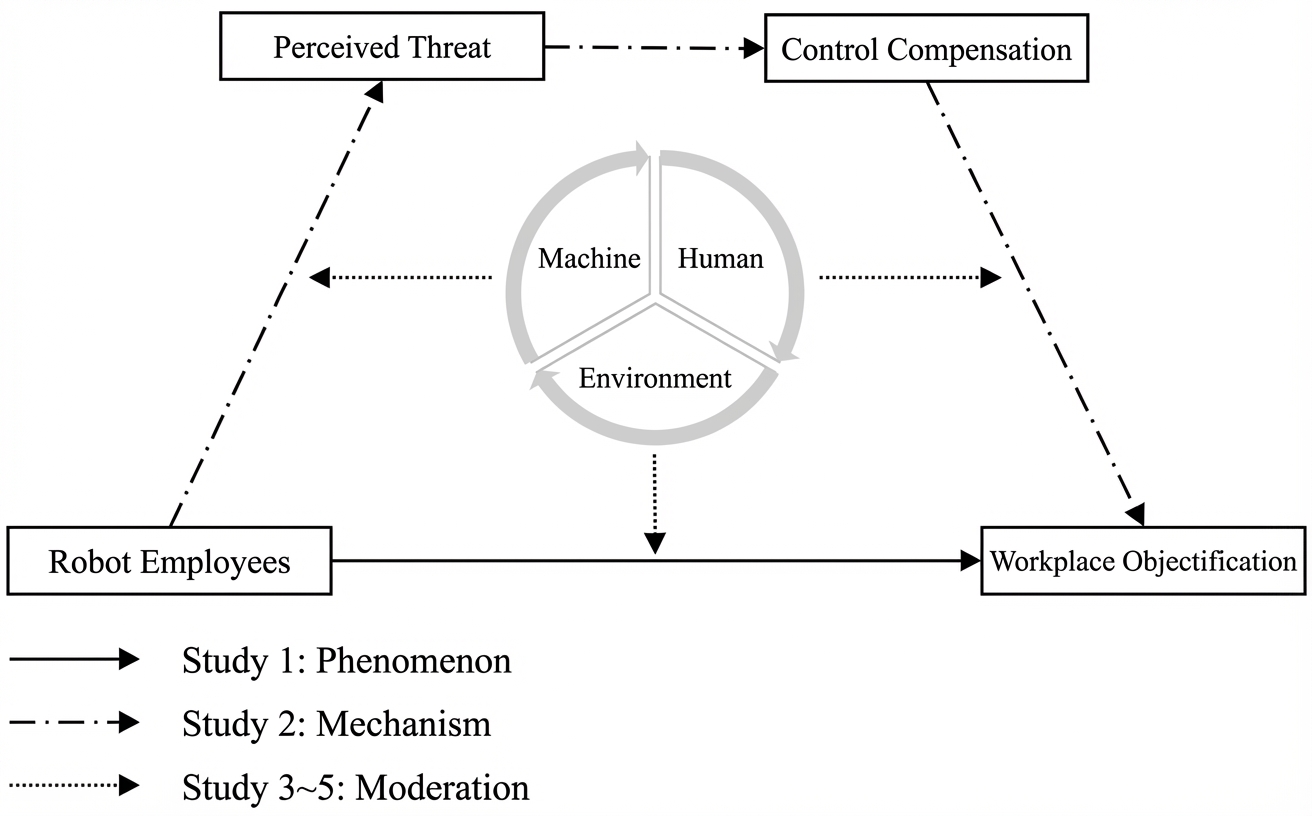

2 Partitioned Image Compression

Pulsar candidate diagnostic images are generated by processing observation data through dedispersion and period folding to obtain possible pulsar rotation parameter combinations and statistical distribution results, which are then plotted for astronomers to determine whether they represent actual pulsars (Figure 1). These diagnostic images primarily contain eight sub-images that can be roughly categorized into three types: sub-images 2 and 3 are two-dimensional grayscale scatter plots containing numerous random noise points; sub-images 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7 are sparse curve plots or text-based binary images; and sub-image 8 is a color image. Visual inspection reveals significant differences among these sub-images, including varying numbers of channels and substantial differences in data sparsity, making it unreasonable to use a single compression algorithm or model. This paper partitions the image region into three categories, applying different compression methods: white block skipping coding for binary image regions, and separate deep network latent variable compression models for grayscale and color images. The three image regions are automatically located, segmented, and distributed to corresponding encoders for compression processing.

2.1 White Block Skipping Coding Method

White block skipping coding is a run-length coding variant that exploits the characteristic that monochrome regions occupy most positions in binary images. One-dimensional white block skipping coding divides each scan line of a binary image into blocks of N pixels. Blocks of all-white pixels are represented by a 1-bit word "0," while blocks containing at least one black pixel are represented by N+1-bit codewords: the first bit "1" serves as a prefix code, and the remaining N bits directly represent the binary amplitude values (white as "0," black as "1"). Extended to two dimensions, the entire image is segmented into M×N pixel blocks. All-white blocks are represented by 1-bit "0," while non-all-white blocks use M×N+1-bit codewords with a prefix bit "1" followed by M×N bits representing the binary amplitude values. For pulsar candidate images, Type 1 regions are segmented and transformed into binary images using a specified threshold, with white pixels represented as "0" and black pixels as "1."

As shown in Figure 2, white block skipping coding generates a binary data stream from the binary image, which is then fed into an adaptive arithmetic coder (QM coder) to further compress bitstream redundancy. This paper employs an improved adaptive hierarchical block-skipping algorithm for white block skipping coding.

2.2 Deep Network Latent Variable Compression Model

For grayscale and color images, this paper trains two separate learned deep network latent variable compression models for corresponding image blocks. The overall network structure is an autoencoder architecture (Figure 3) comprising four components: an analysis transform network module (Encoder), quantizer, entropy coding module (Entropy Coder), and synthesis transform network module (Decoder). The analysis transform network Encoder consists of multiple stacked convolutional layers that perform downsampling, feature extraction, and decorrelation transformations to map the input image to a weakly correlated, compact latent representation. This latent representation retains all necessary image information and constitutes the data to be compressed. The synthesis transform network Decoder performs the inverse operation of the Encoder, also composed of a series of stacked transposed convolutional layers that generate image information through upsampling. The Entropy Coder module depends on a neural network-learned parameter estimation model of the latent representation distribution, guiding the arithmetic coder to convert quantized latent representation information into binary streams for storage and network transmission—that is, the compressed information.

The image feature data x is mapped to latent representation y, the quantizer Q quantizes y to ŷ, the entropy model θ approximates the statistical distribution of ŷ to guide the arithmetic coder in encoding ŷ into a binary stream. During decoding, the arithmetic coder relies on the entropy model to translate the binary stream back into quantized features ŷ, and the synthesis transform D generates image x′ based on ŷ information. The main modules are the analysis transformer E and synthesis transformer D, which differ from traditional transform coding methods in that they are optimized through learning from large image datasets rather than being handcrafted.

The neural network learns model parameters (weights and biases) based on a loss function through backpropagation of error gradients. This paper employs RDO optimization strategy, jointly using image compression distortion and rate functions with Lagrange multiplier β controlling the balance between rate and distortion, as expressed in Equation (1):

$$

L = D(x, x') + \beta \cdot R(\hat{y})

$$

where $D(x, x')$ represents the distortion between original and reconstructed images, and $R(\hat{y})$ represents the bitrate of quantized latent representation.

2.2.1 Quantizer

Compression encoding requires quantization of the latent representation layer output y, typically using rounding operations. This paper employs a quantizer with quantization interval step size of 1, using interval centers to represent quantization output. The quantization formula is:

$$

\hat{y}_i = \text{round}(y_i)

$$

where the indicator i traverses all elements of the vector, including channels and spatial coordinates. This approach enables the marginal density of $\hat{y}$ to be obtained through a trainable discrete probability mass function, with weights equivalent to probability mass function q. As described in the next subsection, the marginal density of continuous variables can be approximated by the difference between the upper and lower limits of the cumulative density function of the discrete probability density function with unit width.

However, analyzing the loss function reveals that it depends on quantized values, yet the gradient of the rounding quantization function is almost always zero, making the loss function composed of rate R and distortion D non-differentiable and preventing gradient descent optimization. To enable stochastic gradient descent, we implement a dithered quantizer by adding independent and identically distributed random uniform noise u during training, where u's distribution interval equals the quantizer's quantization interval width of 1. During testing and actual encoding, we directly use the rounding function, as expressed in Equation (3):

$$

q_i = \begin{cases}

y_i + u, & u \sim \mathcal{U}(-0.5, 0.5), \text{ during training} \

\text{round}(y_i), & \text{ during testing}

\end{cases}

$$

2.2.2 Piecewise Linear Function Entropy Model

The image compression model requires lossless encoding of the compact latent representation obtained from analysis transform to generate binary code streams. This paper employs arithmetic coding for entropy encoding. Arithmetic coding is an optimal lossless entropy coding algorithm that maps all coding information to a small interval [0,1) on the real axis based on the statistical probability distribution of the source information. The foundation of arithmetic coding is accurate estimation of the latent representation distribution model, which affects both rate R and distortion D—that is, the compression performance. We use a non-parametric piecewise linear density function model implemented via neural network to approximate the actual data distribution.

Assuming data in the latent representation space are independent and identically distributed, we can establish a fully factorized model whose likelihood function is the integral of samples, as in Equation (4). The probability density model is obtained by convolving the prior distribution density function of latent representation data with a standard uniform distribution density function. The encoder's output feature map serves as input to generate the prior distribution density model's cumulative function for latent representation features, yielding a unit probability mass centered on actual data.

Following reference [8], we design a non-parametric piecewise linear density function model based on deep neural networks that fits sample data through iterative training optimization. The non-parametric piecewise linear density function constructed using convolutional networks includes K stages of nonlinear transformation functions, where the K-th stage vector mapping function is $f_K': \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^m$, with $\frac{\partial f_K'}{\partial c}$ being the gradient of density p—that is, a Jacobian matrix. The model's cumulative density can be computed via the chain rule as:

$$

p(c) = p_K(f_K' \circ f_{K-1}' \circ \cdots \circ f_1'(c)) \cdot \prod_{k=1}^{K} \left| \det \frac{\partial f_k'}{\partial f_{k-1}'} \right|

$$

The specific implementation of the nonlinear function is as follows:

$$

f_k(x) = g_k(H_k(x) + b_k) \quad \text{for } 1 < k \leq K

$$

where $H_k(x)$ represents the transformation function form before the quantizer layer, and $b_k$ is the bias term. The final layer function $f_K$ uses a nonlinear activation function $\sigma(\cdot)$ to map the probability distribution to the [0,1] interval, representing the standard distribution of probability density.

3 Experiments

We use partial results from recent FAST pulsar search sky survey projects as the image compression training and test datasets, comprising 1,159 pulsar image samples and 998 RFI image samples as 8-bit lossless PNG images. The network model is implemented on an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 GPU using the PyTorch framework. To validate the proposed algorithm's performance, we randomly select five pulsar images from the test set for compression algorithm testing. For binary images, we compare WBS compression with PNG compression; for grayscale and color image regions, we compare our deep compression algorithm with JPEG, JPEG2000, and BPG algorithms. JPEG uses the open-source libjpeg library, JPEG2000 uses openjpeg implementation, and BPG uses the libbpg library.

3.1 White Block Skipping Coding Process

We segment Type 1 image regions from candidate diagnostic images—sparse binary images—and calculate the pixel amplitude histogram to select a threshold of 200 for binarization mapping to {0,1}. Next, we select the white block skipping size; through extensive compression experiments on candidate diagnostic images, we determine the optimal block size as 5×4 to achieve optimal compressed bitstreams. Finally, the white block skipping coded data is fed into the QM arithmetic coder.

3.2 Deep Network Model Structure

The autoencoder's input and output dimensions are consistent, meaning the input image size and channel count match the compressed model's reconstructed image. Our compression network uses image patches of size 256×256. The Encoder module includes four convolutional layers, three GDN layers, and four ResNet layers. Convolutional layers perform 2× downsampling: the first convolutional layer uses 128 9×9 kernels with stride 2 and padding 4; the second and third convolutional layers have 128 5×5 kernels with stride 2 and padding 2; the bottleneck layer is also a convolutional layer with stride 2 and padding 2, with adjustable channels specifying the number of 16×16 feature maps to control bitrate. The Decoder module has similar parameters to the Encoder module, with Conv2d replaced by ConvTranspose2d in reverse order.

Our network model is based on RDO optimization, jointly using compression distortion and bitrate as the target loss function. We train two compression models for grayscale and color images. The Lagrange multiplier λ regulates different distortion-rate combinations to meet various compression quality requirements, enabling variable-rate compression. In experiments, we train ten λ models with λ values of {16, 32, 64, 128, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 6144, 8192}. We optimize models using the Adam algorithm with an initial learning rate of $10^{-3}$, momentum factor of 0.99, and weight decay rate of $10^{-4}$. The iteration count is set to 100,000 with a batch size of 16. We first train a high-bitrate model, then use it as a pretrained model to train other models with adjusted λ values.

3.3 Experimental Results and Analysis

White Block Skipping Coding Performance Evaluation. For Type 1 image regions in candidate diagnostic images, we compare improved WBS compression with basic WBS and PNG compression. Table 1 shows that improved WBS compression achieves five times better performance than PNG, and WBS with QM coding further improves compression performance. Figure 4 reveals that PNG and WBS binary images are essentially identical, though PNG images have smoother edges.

Deep Network Model Objective Evaluation. We set the neural network latent representation layer channel numbers to N=64 for grayscale and N=128 for color images, with a downsampling rate of 16, to train deep network compression models. Since both model types share the same methodology and due to space limitations, we describe only the color image network model's PSNR and SSIM performance at different bitrates. Experimental results in Figure 5(a) show the PSNR-Rate curve, reflecting the mean squared error between decoded and original images across various bitrates. Overall, our deep network compression model (DNCM) performance is similar to JPEG2000, significantly better than JPEG but not exceeding BPG. At 0.4 bpp, DNCM achieves 31 dB PSNR, intersecting with JPEG2000, 1.4 dB higher than JPEG, and 8 dB lower than BPG. The compression effect is clearly superior to JPEG and approaches JPEG2000 and BPG. At near-lossless compression, traditional algorithms outperform neural network methods due to convolutional neural network oversmoothing. Figure 5(b) shows the SSIM-Rate curve, reflecting structural similarity between decoded and original images. DNCM significantly outperforms JPEG and JPEG2000 and slightly exceeds BPG. At 0.2 bpp, DNCM's SSIM value exceeds 0.99, while the best traditional algorithm BPG achieves 0.95. When bpp < 0.7, DNCM's SSIM remains above 0.95, demonstrating its absolute advantage in maintaining perceptual quality at low bitrates and high compression ratios.

Deep Network Model Subjective Evaluation. Figure 6 shows visual results of different compression algorithms at similar bitrates. JPEG exhibits blocking artifacts, while our DNCM algorithm generally matches BPG performance and outperforms JPEG and JPEG2000. The color diagnostic images achieve the best visual quality at relatively low bitrates.

In summary, pulsar diagnostic images contain numerous sparse curves, random noise points in grayscale images, and color image blocks. No single traditional lossy compression algorithm is optimal. Our partitioned strategy utilizing white block skipping coding and neural network compression models provides targeted, specialized compression for diagnostic images. Curve and text image blocks, when converted to binary images, achieve extremely high compression ratios with minimal loss through WBS. Crucially, the network compression module's functional mappings are learned from large diagnostic image datasets, maximizing reflection of diagnostic image data space characteristics and demonstrating model specialization. Since pulsar diagnostic images primarily serve as visual aids for human judgment of pulsar candidates, with observation focusing on curve structures and inter-subimage structural information, our algorithm's ability to maintain high SSIM values at low bitrates reflects its advantage in visual perceptual quality.

4 Conclusion

Pulsar diagnostic images consist of sparse binary images, randomly distributed grayscale images, and color images, making it unreasonable to treat them uniformly with a single transform compression algorithm. This paper proposes a partitioned compression approach using white block skipping coding and deep network compression models. WBS coding, effective for binary images with large monochrome regions, extracts curve and text sub-images from pulsar diagnostic images, selects quantization thresholds to binarize images into bit matrices, chooses optimal block sizes for WBS encoding, and feeds the result into a QM coder to further enhance compression performance, ultimately achieving compression ratios five times better than PNG. The deep network compression method trains separate models for grayscale and color images. The deep network compression model employs a convolutional neural network-based autoencoder structure comprising analysis transform encoding network, quantizer, entropy coder, and synthesis transform encoding network. All compression modules are optimized through learning from large pulsar candidate diagnostic image datasets, providing more effective transform mapping than traditional handcrafted modules. Images are mapped to latent representations that are more compact and decorrelated, while the learned entropy coding module approximates the latent space distribution more accurately and operationally than cumulative probability histograms, guiding statistical distribution-based arithmetic coders for lossless encoding. Experimental results demonstrate that our deep network compression algorithm, when applied to pulsar candidate diagnostic images from recent FAST sky survey projects, achieves PSNR performance superior to JPEG and comparable to JPEG2000, while SSIM performance far exceeds traditional compression algorithms. This paper fully exploits significant feature differences among sub-images, implementing a partitioned compression strategy that divides images into three sub-image regions and applies WBS and deep network compression methods according to sub-image characteristics, improving coding efficiency. We also observe that the neural network-based entropy estimation model used herein is a concise and operational approach, and the accuracy of the estimated entropy model in matching the true latent distribution directly affects rate and distortion. Therefore, considering new methods to improve entropy model estimation accuracy could further enhance compression performance.

References

[1] Xu Yuyun, Li Di, Liu Zhijie, Wang Chen, Wang Pei, Zhang Lei, Pan Zhicheng. Application of Artificial Intelligence in the selection of Pulsar Candidate[J]. Progress in Astronomy, 2017, 35(003):304-315.

[2] Zhu W W, Berndsen A, Madsen E C, et al. Searching for Pulsars Using Image Pattern Recognition[J]. The Astrophysical Journal, 2014, 781(2):117.

[3] Qian L, Pan Z C, Li D, et al. The first pulsar discovered by FAST[J]. Scientia Sinica Physica, Mechanica & Astronomica, 2019, 62(5):71-74.

[4] Yu Q, Pan Z, Qian L, et al. A PRESTO-based Parallel Pulsar Search Pipeline Used for FAST Drift Scan Data[J]. Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2019, 20(6):215-222.

[5] Wallace G K. The JPEG still picture compression standard[J]. Communications of the ACM, 1992, 38(1):xviii-xxxiv.

[6] Taubman D S, Marcellin M W. JPEG 2000: Image Compression Fundamentals, Standards and Practice[J]. Journal of Electronic Imaging, 2002, 11(2):286.

[7] Toderici G, O'Malley S M, Hwang S J, et al. Variable Rate Image Compression with Recurrent Neural Networks[J]. arXiv:1511.06085, 2015.

[8] Balle J, Laparra V, Simoncelli E P. End-to-end Optimized Image Compression[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.01704, 2016.

[9] Theis L, Shi W, Cunningham A, et al. Lossy Image Compression with Compressive Autoencoders[J]. arXiv:1703.00395, 2017.

[10] Liu J, Lu G, Hu Z, et al. A Unified End-to-End Framework for Efficient Deep Image Compression[J]. arXiv:2002.03370, 2020.

[11] Liu Yong, Yin Lixin, Zhao Yang. New Adaptive Block Skipping Coding of Binary Image[J]. Computer Engineering, 2009, 13(35), 219-221.