Abstract

The muon radiography imaging technique for high-atomic-number objects (Z) and large-volume objects via muon transmission imaging and muon multiple scattering imaging remains a popular topic in the field of radiation detection imaging. However, few imaging studies have been reported on low and medium Z objects at the centimeter scale. This paper presents an imaging system that consists of three layers of a position-sensitive detector and four plastic scintillation detectors. It acquires data by coincidence detection technique of cosmic-ray muon and its secondary particles. A 3D imaging algorithm based on the density of the coinciding muon trajectory was developed, and 4D imaging that takes the atomic number dimension into account by considering the secondary particle ratio information was achieved. The resultant reconstructed 3D images could distinguish between a series of cubes with 5-mm side lengths and 2-mm intervals. If the imaging time is more than 20 days, this method can distinguish intervals with a width of 1 mm. The 4D images can specify target objects with low, medium, and high Z values.

Full Text

A Novel 4D Resolution Imaging Method for Low- and Medium-Atomic-Number Objects at the Centimeter Scale Using Coincidence Detection of Cosmic-Ray Muons and Their Secondary Particles

Xuan-Tao Ji¹, Si-Yuan Luo¹, Yu-He Huang¹, Kun Zhu¹, Zhu Jin¹, Xiao-Yu Peng¹, Min Xiao¹, Xiao-Dong Wang¹,*

¹School of Nuclear Science and Technology, University of South China, Hengyang 421001, China

*Corresponding author: wangxd@usc.edu.cn

Abstract: Muon radiography imaging techniques for high-atomic-number (Z) and large-volume objects via muon transmission imaging and muon multiple scattering imaging remain active research areas in radiation detection imaging. However, few imaging studies have focused on low- and medium-Z objects at the centimeter scale. This paper presents an imaging system consisting of three layers of position-sensitive detectors and four plastic scintillation detectors that acquires data through coincidence detection of cosmic-ray muons and their secondary particles. A 3D imaging algorithm based on the density of coinciding muon trajectories was developed, and 4D imaging that incorporates atomic number information by analyzing secondary particle ratios was achieved. The reconstructed 3D images can distinguish between cubes with 5-mm side lengths and 2-mm intervals. With imaging times exceeding 20 days, this method can resolve intervals as small as 1 mm. The 4D images can identify target objects with low, medium, and high Z values.

Keywords: Image reconstruction, Monte Carlo simulation, Non-destructive detection

1. Introduction

In 1936, cosmic-ray muons were first discovered in an electromagnetic field \cite{1}. Muons are particles produced when high-energy cosmic rays interact with atmospheric atoms through cascade showers. With a mass of 105.7 MeV/c²—207 times that of an electron—and a lifetime of approximately 2.2 microseconds, muons reach Earth's surface with average energies of 3–4 GeV (maximum energies reaching the TeV scale) at a flux of approximately 1 cm⁻²min⁻¹. Their angular distribution follows a cos²θ dependence, where θ is the zenith angle \cite{2}. Cosmic-ray muons lose kinetic energy primarily through Coulomb scattering, a process described by the Bethe-Bloch formula \cite{3}. Beyond natural cosmic-ray muon sources, the development of artificial muon sources represents another important research direction \cite{4-7}.

Cosmic-ray muons possess the unique advantages of high penetration capability and non-destructive nature, making them valuable for imaging applications. Current muon imaging technologies fall into two categories: muon multiple scattering imaging and muon transmission imaging. Muon multiple scattering imaging was first applied in 2003 to detect high-Z objects over short time periods by analyzing muon scattering angles using the point of closest approach (POCA) algorithm \cite{8}. This technology has since been primarily used for imaging high-Z materials. The CRIPT system—a large-area muon detector based on scintillators and wavelength-shifting fibers—was constructed to detect potential uranium or plutonium materials in containers \cite{9,10}. Following the Fukushima nuclear accident, muon scattering imaging was employed to visualize nuclear debris inside reactor cores \cite{11}, and the technique has also been applied to material identification \cite{12-14}.

Muon transmission imaging reconstructs target objects by analyzing changes in muon flux after penetration, typically for large-volume structures and natural formations. In 1970, hidden chambers in pyramids were discovered using this technique \cite{15}. Subsequent applications include volcano monitoring \cite{16-21}, bulk cargo ship imaging \cite{22}, and lunar shadow observations \cite{23}. In 2017, researchers published a study imaging a large void in Khufu's Pyramid \cite{24}, and significant progress was made in China in 2020 when a research team completed muon transmission imaging of the Changshu Underground Trench \cite{25}. Various position-sensitive detectors have been designed for different applications. For large-volume targets like volcanoes and pyramids, scintillation detectors with large sensitive areas (exceeding 1000 mm × 1000 mm) but relatively coarse position resolution (worse than 10 mm) are commonly used \cite{26-28}. For high-Z material imaging, gas detectors with superior position resolution (better than 0.5 mm) have been developed, including Micromegas detectors achieving 0.075 mm resolution \cite{29-32}.

Both muon transmission and multiple scattering imaging reconstruct images based on changes in muon trajectory or flux after penetrating target objects, making them most suitable for high-Z and large-volume applications. However, secondary particles produced by muons also carry information about the target. If this information can be fully utilized, additional object characteristics could be observed in a single measurement. The Muon Camera (MUCA) was designed based on secondary particle information and used for imaging bovine bones \cite{33-35}, compensating for limitations in imaging low- and medium-Z objects. Nevertheless, the information carried by secondary particles warrants further exploration for muon imaging applications.

This work proposes and designs a new imaging system based on muon and secondary particle detection techniques. The system comprises three layers of position-sensitive detectors and four fast-timing plastic scintillation detectors with a total volume of 0.125 m³, combining high position resolution with rapid response capabilities. Position-sensitive detectors determine incident muon trajectories, while plastic scintillators measure secondary particles. An algorithm for 3D imaging based on coinciding muon trajectory density was developed, with atomic number resolution achieved through secondary particle information, enabling 4D imaging.

2. Secondary Particle Production and Performance

This section investigates the physical processes, energy spectra, and polar angle distributions of secondary particles. Secondary particles include gamma rays, electrons, and a few positrons. Since positron yields are several orders of magnitude lower than other particles, only secondary electrons and gamma rays were considered.

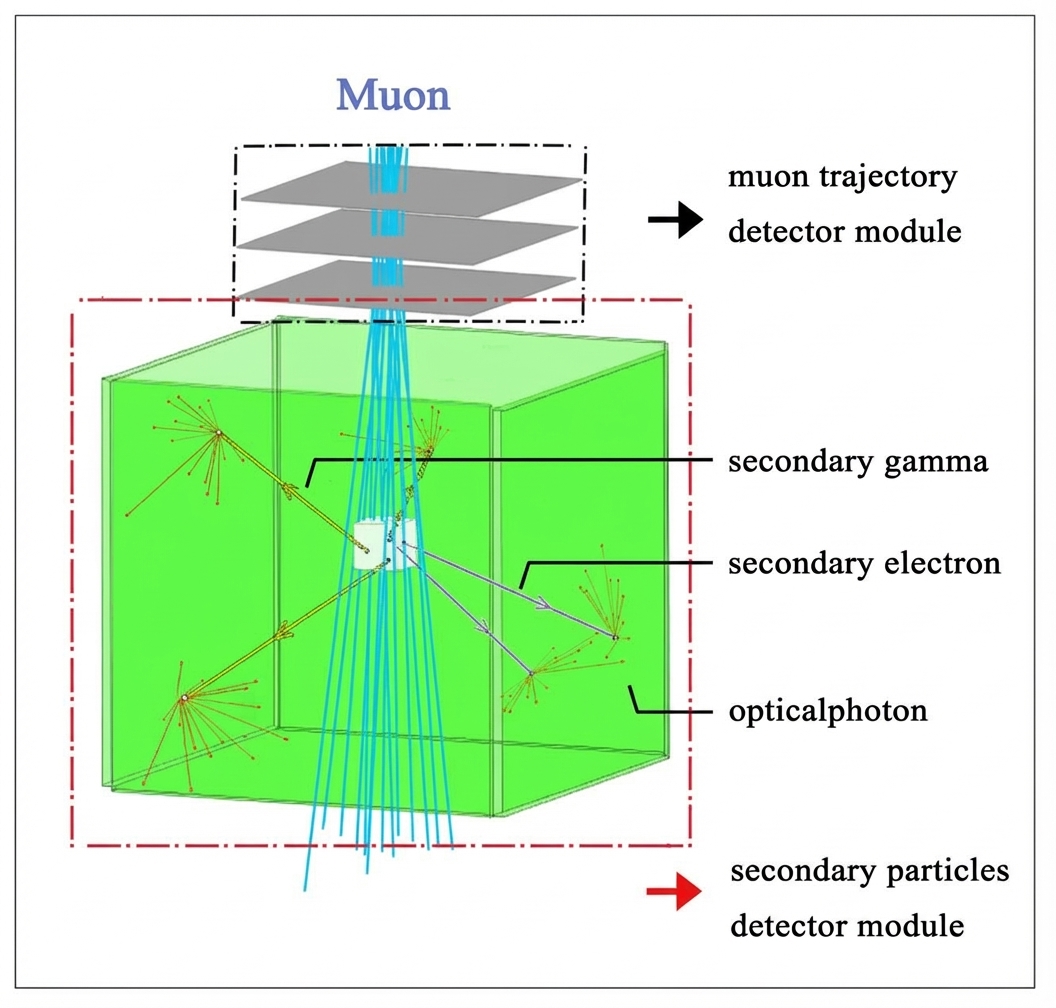

2.1.1 Detector System Geometry

Simulations were performed using GEANT4.10.6p-03, with the generic model visualized through the Geant4 OpenGL interface (Figure 1). The detector system consists of two modules. The muon trajectory detector module comprises three layers of position-sensitive detectors that obtain precise muon hit positions and reconstruct trajectories. Each detector measures 400 mm × 400 mm × 10 mm, with 50 mm spacing between the bottom of the top detector and the top of the bottom detector. Located at the system's top, these detectors are micro-filter gaseous detectors. The secondary particle detector module consists of four EJ200 scintillation detectors in a box-like configuration surrounding the target object. Designed for large detection coverage, each scintillator measures 500 mm × 500 mm × 50 mm. Compared to muon multiple scattering imaging systems, this new system requires only four additional scintillation detectors, making the two approaches readily compatible. The central white cube represents a 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm target object. When an incident muon penetrates this cube, secondary particles may be produced and recorded by the secondary particle detector module. Geant4 simulations were developed to study secondary particle generation and information extraction.

2.1.2 Primary Particles

The G4VUserPrimaryGeneratorAction class in Geant4 defines primary particles. Muons (μ⁻) were generated with an energy spectrum following the natural distribution detailed in M. Tanabashi, P.D. Grp, K. Hagiwara et al. \cite{3} (average energy 3–4 GeV, maximum reaching TeV scale). To simulate cosmic-ray muon zenith angles, momentum directions were sampled from a cos²θ distribution, with larger polar angles corresponding to fewer incident muons. Initial muon positions were selected with fixed z-coordinates above the muon trajectory detector module and x- and y-coordinates uniformly distributed between x_min to x_max and y_min to y_max, respectively.

2.1.3 Physics Lists

Physical processes were defined using the G4VModularPhysics class in Geant4, incorporating four modules: G4DecayPhysics, G4RadioactiveDecayPhysics, G4EmStandardPhysics, and G4OpticalPhysics.

2.1.4 EventAction

The EventAction class, based on G4UserEventAction, initializes both detector modules to zero at each event's start. When secondary particles pass through scintillation detectors, the secondary particle detector module value is set to 1 and particle information is recorded.

2.2 Secondary Particles Produced by Muons

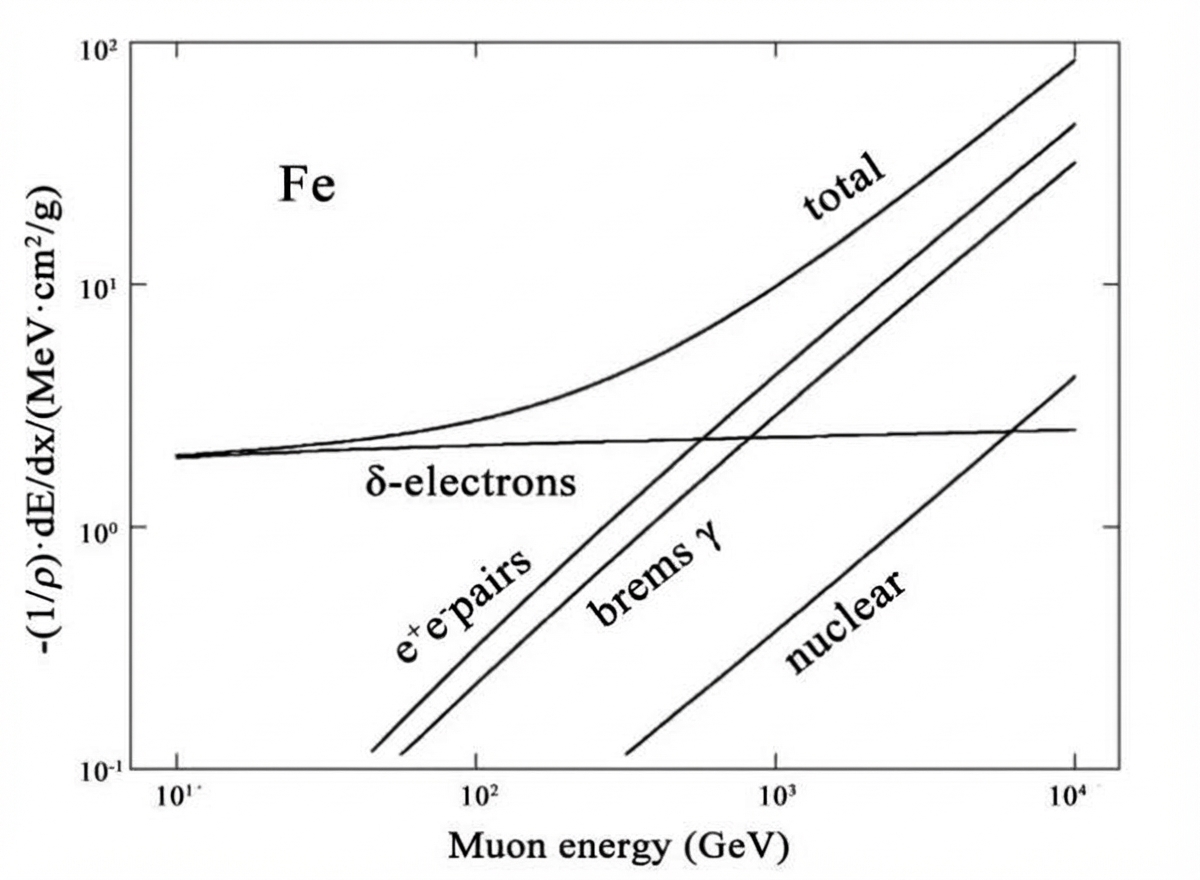

Ionization, bremsstrahlung, and pair production constitute the three principal interaction mechanisms between muons and target objects. Figure 2 shows muon energy loss through different interactions for an iron target. Ionization energy loss remains nearly constant with energy and dominates below 570 GeV. Bremsstrahlung and pair production energy losses increase rapidly with muon energy, becoming dominant above 570 GeV. For cosmic-ray muons with average energies of 3–4 GeV, secondary electrons are primarily ionized δ-electrons and secondary ionization electrons, while secondary gamma rays are produced through bremsstrahlung from these electrons.

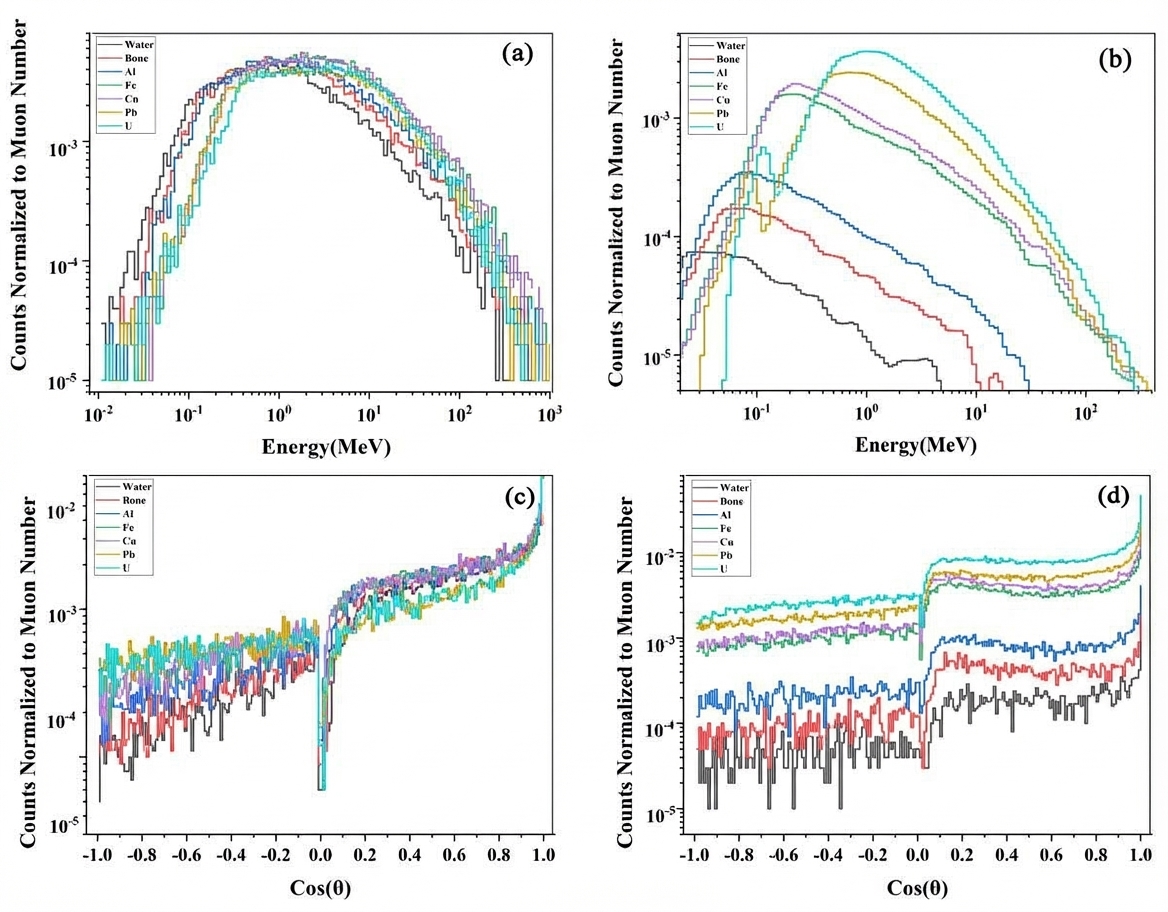

2.3 Secondary Particle Energy Spectra

Figures 3(a) and 3(b) present secondary electron and gamma energy spectra from Geant4 simulations. The secondary electron energy spectrum shows minimal variation across materials, with counts first increasing then decreasing with atomic number Z due to competing ionization and self-absorption effects. Consequently, medium-Z targets produce the highest secondary electron yields. For secondary gamma rays, δ-electrons from muon ionization continue to ionize the target and undergo bremsstrahlung, concentrating the gamma spectrum peak below 1 MeV. As Z increases, the peak shifts to higher energies and counts increase due to greater ionization energy loss and weaker gamma self-absorption. Secondary particle counts vary significantly in the 0.1–100 MeV energy range, suggesting this region can potentially distinguish target Z values.

2.4 Polar Angle Distribution of Secondary Particles

Figures 3(c) and 3(d) show secondary particle polar angle distributions. To capture complete angular information, emission angles upon leaving the target object were recorded rather than scintillator-recorded data. The horizontal axis represents the angle between secondary particles and the muon trajectory. Both secondary electrons and gamma rays are most likely emitted along the muon trajectory direction. For lead and uranium, secondary electrons show higher probabilities of backward emission compared to other materials, as high-Z targets cause greater electron deflection. However, atomic number has limited effect on the overall polar angle distribution.

3. Imaging Algorithm

3.1 Coinciding Muon Trajectory

In Geant4 simulations, an incident muon trajectory is recorded as a coinciding muon trajectory only when both detector modules respond within a short time window. Since muons and secondary particles travel near light speed, this window is approximately 1 ns. The EJ200 scintillator for secondary particle detection provides fast response (0.9 ns rise time, 2.1 ns decay time) and short pulse width (FWHM = 2.5 ns) to distinguish secondary particles from background noise. As secondary particles are generated when muons ionize target material, coinciding muon trajectories ideally form straight lines penetrating the target. In realistic experimental environments with air, these trajectories have high probability of passing through the target object. For low- and medium-Z objects where muon trajectory changes are minimal, the incident muon trajectory is assumed to be a straight line. With sufficient coinciding muon trajectories, target objects can be reconstructed.

3.2 Imaging Algorithm

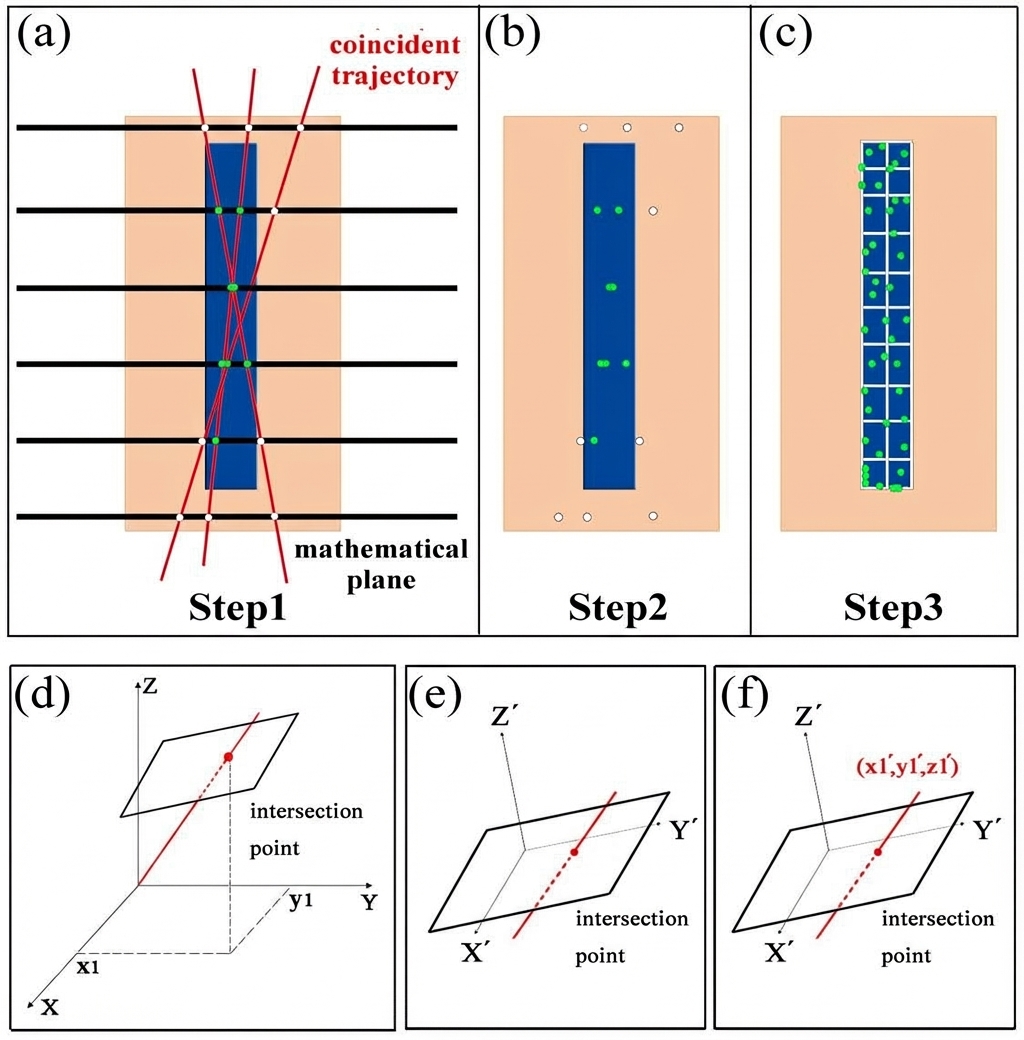

Regions where numerous coinciding muon trajectories intersect indicate target object locations. The reconstruction method proceeds as follows (Figure 4): First, a series of mathematical planes are defined and intersection coordinates between all coinciding muon trajectories and these planes are calculated (Figure 4(a)). Second, the highest-density intersection region is selected (Figure 4(b)), where intersection points are represented as dots—hollow white dots indicate points outside the object, while solid green dots represent successful reconstruction events inside the object. Third, selected points are converted to voxel assignments (Figure 4(c)), enabling 2D and 3D image reconstruction.

When mathematical planes are perpendicular to the Z-axis, intersection coordinate calculation reduces to finding where a 3D line meets a Z-perpendicular plane. The Z-axis distribution of intersection points differs, with highest density reflecting the target object's height. Secondary particle production dominates within this height interval. For planes above or below the target, intersection distributions show radial and mesh patterns. By selecting high-density regions using appropriate thresholds, target material height can be determined. The algorithm can be extended to non-Z-perpendicular planes (Figure 4(d)), allowing object distribution determination along any plane's normal vector. Continuously varying the mathematical plane orientation enables tomographic reconstruction with improved accuracy.

Calculating intersections for arbitrarily oriented planes is more complex. A simplified method involves: First, establishing a new coordinate system XYZ where the Z-axis is perpendicular to the given mathematical plane (Figure 4(e)). Basis vectors (i, j, k) of the original XYZ system transform to the new system's basis vectors (i, j, k) through:

[Equation for basis vector transformation would appear here]

where α₁, α₂, α₃ denote angles between the X-axis and the X, Y, Z axes respectively, while β₁, β₂, β₃, γ₁, γ₂, γ₃ represent corresponding angles for the Y and Z axes. In this new coordinate system, intersection coordinates can be calculated using the Z-perpendicular plane method. Second, these coordinates are transformed back to the original XYZ system (Figure 4(f)) using:

[Equation for coordinate transformation would appear here]

where x₁, y₁, z₁ are the intersection coordinates for non-Z-perpendicular planes.

4. Three-Dimensional Imaging Results

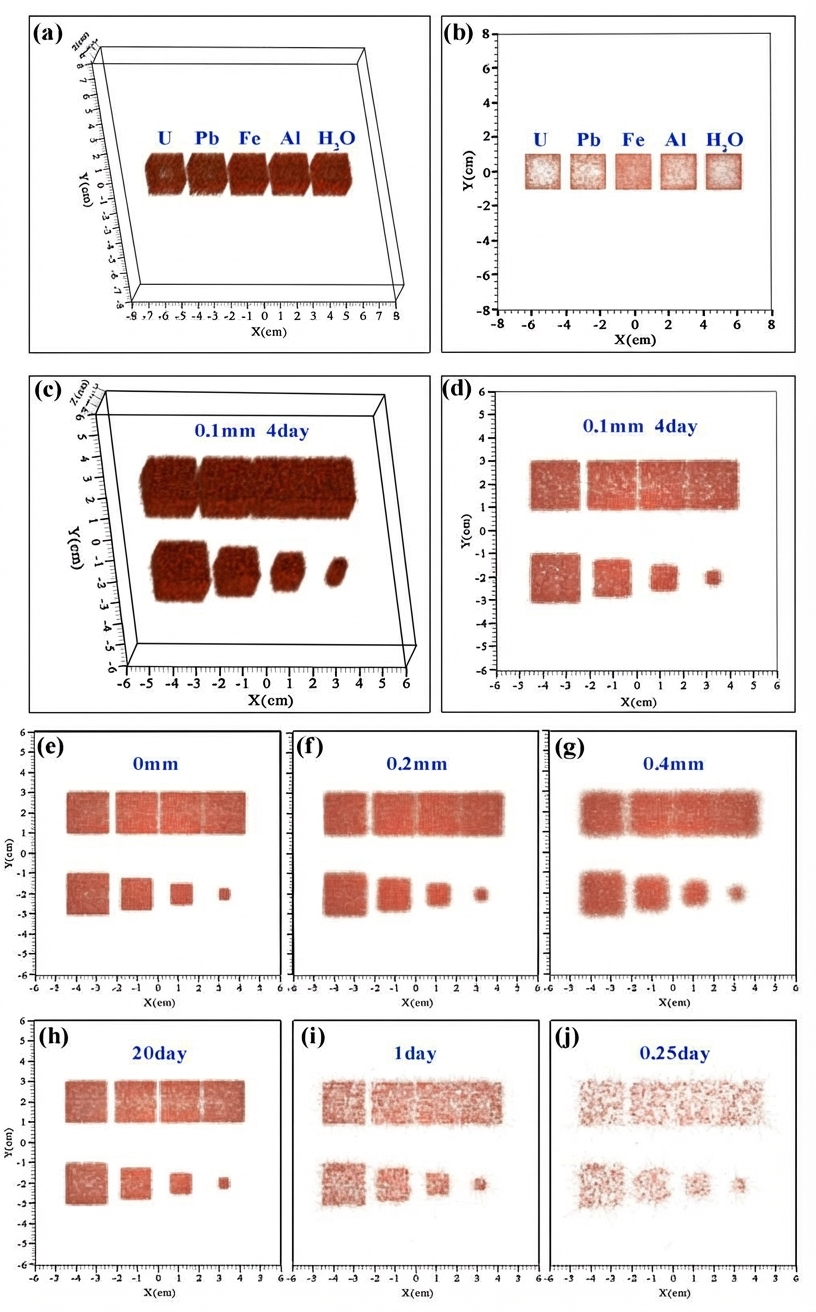

4.1 3D Imaging Performance

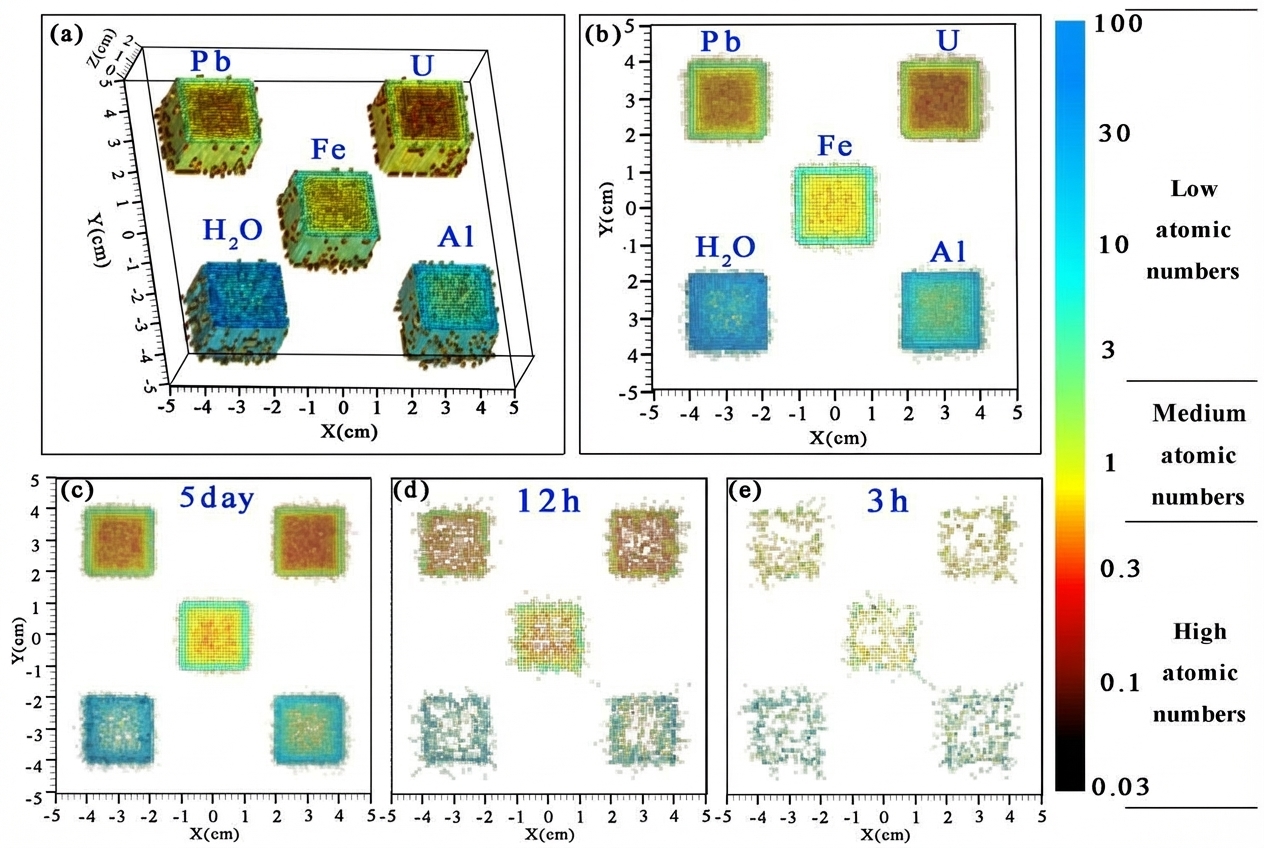

Since ionization loss and self-absorption depend on atomic number Z, imaging quality varies across materials. Figures 5(a) and 5(b) show 3D and top-view images of five 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm cubes made of H₂O, Al, Fe, Pb, and U. Due to uranium's substantially larger data yield compared to water, direct imaging would obscure the water signal, so simulations for each material were performed under identical conditions and then combined for comparison. For Pb and U, strong self-absorption in high-Z materials prevents secondary particles generated within the cube interior from escaping, creating large voids in the central regions. Consequently, imaging high-Z targets may lose central object information. Additionally, the straight-line muon trajectory assumption fails for high-Z materials, introducing larger errors than for other materials. For Al and H₂O, lower ionization losses in low-Z materials produce fewer coinciding muon trajectories, also creating some voids. However, this data insufficiency can be remedied by extending imaging time. Iron demonstrates the best imaging performance among all materials tested. In summary, this method effectively images low- and medium-Z objects, with optimal performance for medium-Z materials, but is less suitable for high-Z objects.

4.2 3D Imaging Accuracy

To evaluate imaging accuracy, iron cubes were used as they provide the best reconstruction quality. Figures 5(c) and 5(d) show 3D and top-view images of eight iron cubes (20 mm height). In one column, cube intervals progressively decrease to 4 mm, 2 mm, and 1 mm. In the other column, cube volumes decrease simultaneously. Given that experimental position resolution is approximately 0.1 mm, simulations included Gaussian-distributed 0.1 mm position uncertainty to model realistic conditions. Approximately 9×10⁶ muons were generated in the muon trajectory detector module, equivalent to 4 days of muon flux. The reconstruction accurately matches Geant4 modeling for all cubes except the 5-mm side length cubes with 1-mm intervals, which remain unresolved. Due to the small volume of 5-mm cubes, height determination via thresholding reconstructs them approximately 4 mm shorter than larger cubes. With 4 days of imaging time and 0.1 mm position resolution, this method accurately reconstructs target object size and position, achieving sufficient resolution to distinguish 5-mm cubes with 2-mm intervals.

4.3 Influence of Position Resolution on 3D Imaging

Position resolution is a critical parameter for detectors, representing the minimum distinguishable separation between incident particles and directly affecting reconstruction quality. Since most applications achieve resolution no better than 0.1 mm, poorer resolution scenarios were investigated. Maintaining 4 days of muon flux, Figures 5(e), 5(f), and 5(g) show reconstructions with 0 mm, 0.2 mm, and 0.4 mm position resolution. As resolution degrades, image edges become increasingly blurred and volumes expand slightly. With perfect (0 µm) resolution, 2-mm intervals are clearly resolved while 1-mm intervals remain invisible. At 0.2 mm resolution, 2-mm intervals become mostly filled and difficult to distinguish. At 0.4 mm resolution, even 4-mm intervals become barely resolvable. Additionally, the second line's smallest cube (5 mm side length) appears circular rather than cubic, unlike the three larger cubes ahead of it. Comparing with the 0.1 mm resolution result (Figure 5(d)), resolution better than 0.1 mm resolves 2-mm intervals, but at 0.2 mm the minimum distinguishable separation increases to 4 mm. At 0.4 mm resolution, neither 4-mm intervals nor 5-mm cubes are distinguishable. Nevertheless, larger cubes (20 mm, 15 mm, 10 mm) remain correctly reconstructed even with poor position resolution.

4.4 Influence of Imaging Time on 3D Imaging

Imaging time directly affects data statistics. With 0.1 mm position resolution, Figures 5(h), 5(i), and 5(j) show results for 20 days, 1 day, and 0.25 days of imaging. With 20 days (approximately 5×10⁷ muons), the minimum resolvable interval reaches 1 mm. At 4 days or 1 day, 2-mm and 4-mm intervals remain distinguishable. However, at 0.25 days, significant reconstruction distortion occurs, making 4-mm intervals and first-line cubes difficult to resolve. In summary, imaging times of 20 days, 4 days, and 1 day can accurately distinguish 5-mm cubes with 1-mm, 2-mm, and 4-mm intervals respectively. Imaging times of 0.25 days or less challenge centimeter-scale 3D reconstruction.

5. Four-Dimensional Imaging

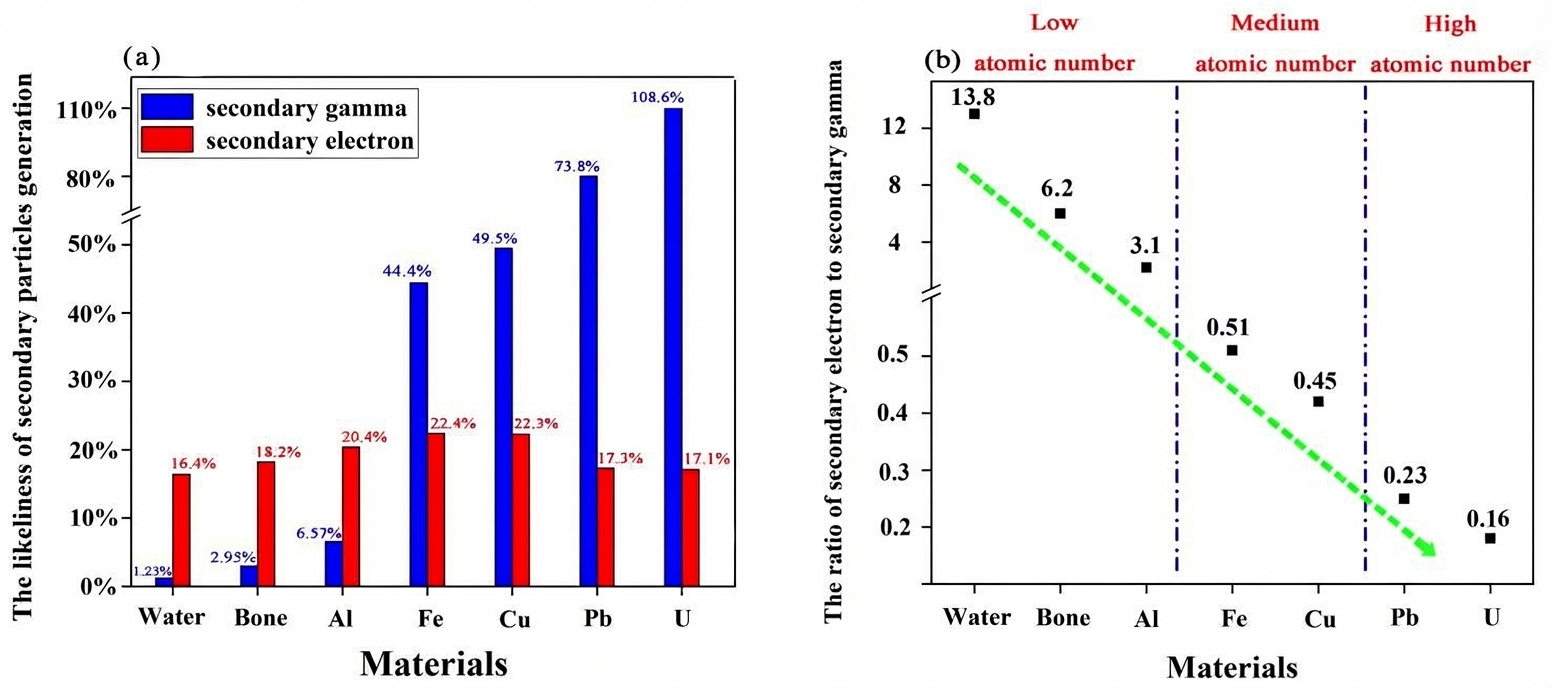

5.1 Secondary Electron to Gamma Ratio

Figures 3(a) and 3(b) demonstrate that secondary electron and gamma counts vary with target Z, enabling material discrimination through particle generation likelihood in the 0.1–100 MeV range (Figure 6(a)). For lead, 100 incident muons produce approximately 17 secondary electrons and 74 secondary gamma rays. The ratio between these particle types varies systematically with material. Figure 6(b) shows the secondary electron-to-gamma ratio decreasing consistently with increasing Z, allowing material identification based on ratio ranges.

5.2 4D Imaging Results

Four-dimensional imaging adds atomic number resolution to 3D spatial reconstruction. The process involves: first, reconstructing separate 3D images using secondary electrons and secondary gamma rays to obtain two 3D matrices; second, dividing corresponding voxels between matrices to create a new 3D matrix whose voxel values represent electron-to-gamma ratios; and third, converting these ratios to colors to produce 4D images. Figures 7(a) and 7(b) show 4D imaging results for 20 days of data with 0.1 mm position resolution. Five 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm cubes (H₂O, Al, Fe, Pb, U) were imaged simultaneously. The top view clearly distinguishes all five materials by their characteristic electron-to-gamma ratios. Color loops surrounding the cubes occur because surface-generated secondary electrons are less absorbed, creating higher voxel ratios than interior regions. Since the ratio also varies with volume, a database encompassing different volume and material ratios would improve target specification.

5.3 Influence of Imaging Time on 4D Imaging

Figures 7(c), (d), and (e) show 4D imaging results for different durations. With 5 days of imaging, the system distinguishes low-, medium-, and high-Z objects. At 12 hours, medium- and high-Z objects become difficult to differentiate, though low-Z targets remain clear. At only 3 hours, shape discrimination fails, but low-Z objects can still be distinguished from medium-Z materials. Thus, low- and medium-Z objects are easily differentiated, while medium- and high-Z objects are less distinguishable. Since muon multiple scattering imaging excels for medium- and high-Z objects, combining both systems would yield superior overall performance.

6. Conclusion

A muon imaging method based on coincident muon trajectories was investigated, encompassing secondary particle generation physics, 3D imaging, and 4D imaging. Secondary particles are primarily produced through muon ionization and δ-electron bremsstrahlung, consisting mainly of electrons and gamma rays. The secondary electron energy spectrum shows little Z dependence, while the secondary gamma spectrum peak shifts to higher energies as Z increases. For 3D imaging with 0.1 mm position resolution, the method achieves reliable accuracy for 5-mm cubes with 2-mm intervals. With imaging times exceeding 20 days, 1-mm intervals can be resolved. In 4D imaging, low-, medium-, and high-Z targets can be distinguished, though imaging times under 0.5 days only differentiate low-Z from medium- or high-Z objects. A comprehensive database of various volumes and materials would further improve performance.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Xuan-Tao Ji, Si-Yuan Luo, Yu-He Huang, and Xiao-Dong Wang. Xuan-Tao Ji wrote the first manuscript draft, and all authors commented on previous versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China Foundation (No. 2020YFE0202001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11875163), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2021JJ20006).

References

- S.H. Neddermeyer, C.D. Anderson, Cosmic-ray particles of intermediate mass. Phys. Rev. 54, 88 (1938). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.54.88

- J.W. Lin, Y.F. Chen, R.J. Sheu et al., Measurement of angular distribution of cosmic-ray muon fluence rate. Nucl. Instru. and Meth. A 619, 24-27 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2009.12.017

- M. Tanabashi, P.D. Grp, K. Hagiwara et al., Review of particle physics: Particle data group. Phys. Rev. D. 98, 030001 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.98.030001

- Z.W. Pan, J.Y. Dong, X.J. Ni et al., Conceptual design and update of the 128-channel μSR prototype spectrometer based on musrSim. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 123 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0648-5

- L.P. Zhou, Q.L. Mu, H.T. Jing et al., A possible scheme for the surface muon beamline at CSNS. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 169 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0684-1

- R.H. Bernstein, P.S. Cooper, Charged lepton flavor violation: An experimenter's guide. Phys. Rep. 532, 27-64 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2013.07.002

- Y. Kuno, A search for muon-to-electron conversion at J-PARC: the COMET experiment. Prog. Theor. Phys. 2013, 2, 022C01 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/ptep/pts089

- K.N. Borozdin, G.E. Hogan, C. Morris et al., Surveillance: Radiographic imaging with cosmic-ray muons. Nature 422, 277 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/422277a

- P.L. Rocca, V. Antonuccio, M. Bandieramonte et al., Search for hidden high-Z materials inside containers with the Muon Portal Project. J. Instrum. 9, C01056 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/9/01/C01056

- J. Armitage, J. Botte, K. Boudjemline et al., First images from the cript muon tomography system. Int. J. Mod. Phys. Conf. Ser 27, 1460129 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1142/S201019451460129X

- K. Borozdin, S. Greene, Z. Lukic et al., Cosmic ray radiography of the damaged cores of the Fukushima reactors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 152501 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.109.152501

- X.Y. Pan, Y.F. Zheng, Z. Zeng et al., Experimental validation of material discrimination ability of muon scattering tomography at the TUMUTY facility. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 120 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0649-4

- S. Xiao, W.B. He, M.C. Lan et al., A modified multi-group model of angular and momentum distribution of cosmic ray muons for thickness measurement and material discrimination of slabs. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 28 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0363-7

- J.N. Dong, Y.L. Zhang, Z.Y. Zhang et al., Position-sensitive plastic scintillator detector with WLS-fiber readout. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 117 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0449-2

- L.W. Alvarez, J.A. Anderson, F.E. Bedwei et al. Search for hidden chambers in the pyramids. Science. 167, 3919 (1970). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.167.3919.832

- HKM. Tanaka, T. Uchida, M. Tanaka et al. Cosmic-ray muon imaging of magma in a conduit: Degassing process of Satsuma-Iwojima Volcano. GEOPHYS. RES. LETT. 36, L01304 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL036451

- K. Jourde, D. Gibert, J. Marteau et al., Muon dynamic radiography of density changes induced by hydrothermal activity at the La Soufrière of Guadeloupe volcano. Sci. Rep. 6, 33406 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33406

- V. Tioukov, A. Alexandrov, C. Bozza et al., First muography of Stromboli volcano. Sci. Rep. 9, 6695 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43131-8

- N. Lesparre, J. Marteau, Y. Declais et al., Design and operation of a field telescope for cosmic ray geophysical tomography. Geosci, Instrum. Method. Data Syst. 1, 33 (2012). https://doi.org/10.5194/gi-1-33-2012

- C. Carloganu, V. Niess, S. Bene et al., Towards a muon radiography of the Puy de Dme. Geosci. Instrum, Method. Data Syst. 2, 55 (2013). https://doi.org/10.5194/gi-2-55-2013

- A. Anastasio, F. Ambrosino, D. Basta et al., The MU-RAY experiment. An application of SiPM technology to the understanding of volcanic phenomena. Nucl. Instru. and Meth. A 718, 134-137 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2012.08.065

- VV. Kobylyansky, VV. Moiseichenko, AI. Myagkikh et al., The deep-sea Cerenkov muon detector with spatial structure. Sov. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 3, 149-153 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02197621

- N. Lesparre, D. Gibert, J. Marteau et al., Geophysical muon imaging: feasibility and limits. Geophys. J. Int. 183, 1348-1361 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04790.x

- K. Morishima, M. Kuno, A. Nishio et al., Discovery of a big void in Khufu's Pyramid by observation of cosmic-ray muons. Nature 552, 386-390 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24647

- R. Han, Q.Yu, Z. Li et al. Cosmic muon flux measurement and tunnel overburden structure imaging. J. Instrum. 15, P06019 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/15/06/P06019

- K. Nagamine, M. Iwasaki, K. Shimomura et al., Method of probing inner-structure of geophysical substance with the horizontal cosmic-ray muons and possible application to volcanic eruption prediction. Nucl. Instru. Meth. A 356, 585-595 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(94)01169-9

- A. Anastasio, F. Ambrosino, D. Basta et al., The MU-RAY detector for muon radiography of volcanoes. Nucl. Instru. Meth. A 732, 423-426 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2013.05.159

- K. Jourde, D. Gibert, J. Marteau et al., Muon dynamic radiography of density changes induced by hydrothermal activity at the La Soufrière of Guadeloupe volcano. Sci. Rep. 6, 33406 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33406

- S. Pesente, S. Vanini, M. Benettoni et al., First results on material identification and imaging with a large-volume muon tomography prototype. Nucl. Instru. and Meth. A 604, 3 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2009.03.017

- K. Gnanvo, L.V. Grasso, M. Hohlmann et al., Imaging of high-Z material for nuclear contraband detection with a minimal prototype of a Muon Tomography station based on GEM detectors. Nucl. Instru. Meth. A 652, 16-20 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2011.01.163

- S. Bouteille, D. Attie, P. Baron et al., A Micromegas-based telescope for muon tomography: The WatTo experiment. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 834, 223-228 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.08.002

- J. Feng, Z. Zhang, J. Liu et al., A thermal bonding method for manufacturing Micromegas detectors. Nucl. Instru. Meth. A 989, 164958(2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2020.164958

- I. Bikit, D. Mrdja, K. Bikit et al., Novel approach to imaging by cosmic-ray muons. EPL 113, 58001 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/113/58001

- D. Mrdja, I. Bikit, K. Bikit et al., First cosmic-ray images of bone and soft tissue. EPL 116, 48003 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/116/48003

- G. Galgoczi, D. Mrdja, I. Bikit et al., Imaging by muons and their induced secondary particles—a novel technique. J. Instrum. 15, 6 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/15/06/C06014

- A.G. Bogdanov, H. Burkhardt, V.N. Ivanchenko et al. Geant4 simulation of production and interaction of Muons. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 53, 2 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2006.872633