Abstract

The transport cross-section based on inflow transport approximation can significantly improve the accuracy of light water reactor (LWR) analysis, especially for the treatment of the anisotropic scattering effect. The previous inflow transport approximation is based on the moderator cross-section and normalized fission source, which is approximated using transport theory. Although the accuracy of reactivity is increased, the P0 flux moment has a large error in the Monte Carlo code. In this study, an improved inflow transport approximation was introduced with homogenization techniques, applying the homogenized cross-section and accurate fission source. The numerical results indicated that the improved inflow transport approximation can increase the P0 flux moment accuracy and maintain the reactivity calculation precision with the previous inflow transport approximation in typical LWR cases. In addition to this investigation, the improved inflow transport approximation is related to the temperature factors. The improved inflow transport approximation is flexible and accurate in the treatment of the anisotropic scattering effect, which can be directly used in the temperature-dependent nuclear data library.

Full Text

Abstract

The transport cross-section based on inflow transport approximation can significantly improve the accuracy of light water reactor (LWR) analysis, particularly in treating the anisotropic scattering effect. Previous implementations of inflow transport approximation relied on moderator cross-sections and a normalized fission source approximated using transport theory. While this approach enhanced reactivity accuracy, it introduced substantial errors in the P0 flux moment when used in Monte Carlo codes.

This study introduces an improved inflow transport approximation incorporating homogenization techniques that employ homogenized cross-sections and an accurate fission source. Numerical results demonstrate that the improved method enhances P0 flux moment accuracy while maintaining the same level of reactivity calculation precision as the previous inflow transport approximation for typical LWR cases. Additionally, the improved approximation exhibits temperature dependence, making it flexible and accurate for treating anisotropic scattering effects and enabling direct application in temperature-dependent nuclear data libraries.

Keywords: Inflow transport approximation; Anisotropic scattering effect; Homogenization techniques; Light water reactor

Introduction

In light water reactor (LWR) analysis, the anisotropic scattering effect is typically treated using simplified approximations such as the transport cross-section (XS) with isotropic scattering, primarily for computational efficiency. This approximation has been widely applied in general LWR problems and has accumulated substantial operational experience despite its simplicity. However, recent studies indicate that the conventional approximation becomes inaccurate in several scenarios, including high-leakage systems, small cores, and fuel assemblies with control rods [1][2]. Consequently, proper treatment of anisotropic scattering effects has become increasingly important for modern lattice physics codes.

Three major challenges exist in treating anisotropic scattering effects. First, higher-order scattering matrices are required. While P2 or higher-order scattering matrices are sufficient to maintain calculation accuracy [3], they demand substantial memory and computational time. The Michigan Parallel Characteristics Transport (MPACT) code implements high-order scattering matrices for whole-core calculations using P2 scattering approximation [4]. Second, angular-dependent total cross-sections can be employed, obtained through angular flux condensation [5][6][7]. However, this approach requires time-consuming Monte Carlo simulations and accurate angular flux determination remains difficult. One study demonstrated that 160 batches with 1 billion neutrons per tally were needed to achieve converged results [8], making this method impractical. Third, transport approximation for transport cross-sections offers an alternative [9]. This approach can be used with P0 scattering matrices and is efficient for large-core calculations. Nevertheless, the key to accurate inflow transport approximation lies in obtaining precise higher-order flux moments from neutron transport calculations. Yamamoto [2] adopted a typical neutron spectrum for the P0 flux moment, with higher-order flux moments inversely proportional to the total cross-section, but this did not improve reactivity accuracy compared to the outflow transport approximation. Choi [10] developed an inflow transport approximation from a one-dimensional PN transport equation that improved accuracy in highly anisotropic scattering cases. However, Choi's one-dimensional PN transport equation was based on the moderator region with normalized fission source, representing a theoretical model approximation. Despite improved reactivity calculation accuracy in highly anisotropic scattering cases, the method remained approximate. Numerous other studies have addressed neutron transport problems and cross-section treatment [11][12][13].

This study investigates the improved inflow transport approximation and tests its application across various LWR cases. The transport cross-section is computed by solving the one-dimensional PN transport equation with homogenized cross-sections and accurate fission source, verified through typical LWR cases. The accuracy and applicability of these transport approximation methods are evaluated by comparing k-infinity, k-effective, and P0 flux moments against reference results. The investigation extends to testing the improved inflow transport approximation across different typical LWR cases. Furthermore, results from the inflow transport approximations implemented in the DRAGON5.0.5 lattice code [14] are compared against experimental values and the Monte Carlo code cosRMC [15]. Numerical results show that the improved inflow transport approximation achieves higher P0 flux moment accuracy than the previous method while retaining equivalent reactivity calculation precision. Additionally, verification through typical LWR cases demonstrates that the improved inflow transport approximation depends only on temperature factors. Consequently, the improved inflow transport approximation provides precise and flexible analysis for LWR applications when implemented in temperature-dependent nuclear data libraries.

The remainder of this manuscript is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the theory and methodology of different inflow transport approximations. Section 3 analyzes discrepancies between the two methods. Section 4 presents numerical results for various LWR cases. Conclusions are presented in Section 5.

2.1 Previous Inflow Transport Approximation

The previous inflow transport approximation, developed by Choi, is based on the moderator region and normalized fission source. The multi-group form of the one-dimensional PN transport equation is derived as follows:

Where $\psi_g(\mu)$ is the angular flux in group $g$, $\mu$ is the cosine angle in the z-direction, $P_l(\mu)$ is the Legendre polynomial, $l$ is the order of the Legendre polynomial, $\Sigma_{x,l}^g$ is the $l$-th moment macroscopic cross-section for reaction $x$ (f: fission, t: total, s: scattering), and $\phi_l^g$ is the $l$-th flux moment.

It should be noted that the distinction between $\tau_{n,l}^g$ and $\tau_{n,l}^{g'}$ (n=1,2…) disappears in the absence of self-shielding (i.e., infinite dilution) [16].

The multigroup transport equation in Eq. (1) can be extended using Eqs. (2)–(5) as follows:

Multiplying Eq. (6) by the Legendre polynomial and integrating from –1 to +1, and using Bonnet's recursion formula and the orthogonality of Legendre polynomials:

Inserting Eqs. (7) and (8) into Eq. (6) yields:

Approximating the spatial shape using buckling $B$:

Inserting Eq. (10) into Eq. (9) produces:

Additionally, another approximation was introduced for Choi's method. The fission source is forced to normalize, and the $k$-eigenvalue is set to 1, leading to:

In Choi's method, Eq. (11) is then converted to:

Solving Eq. (13) for $\phi_n^g$ leads to:

Where the transport cross-section $\Sigma_{tr}^g$ is written as:

When $n$ is an even number and $n-1$ and $n+1$ are odd numbers.

For $n-1$:

For $n+1$:

Inserting Eqs. (16) and (17) into Eq. (14) leads to:

Where

If the order of $n$ is the maximum value, $\phi_{n+1}^g$ becomes 0. For odd $n$, Eq. (14) becomes:

The high-order flux moments and P0 transport cross-section are then generated. Furthermore, the P0 scattering matrix is calculated using the transport cross-section and can be used in transport computations. Only the corrected diagonal elements are as follows:

The transport equation is related to the geometric value $z$. It was calculated for a moderator-dominated material in each problem case, yielding problem-dependent results.

2.2 Improved Inflow Transport Approximation

The above derivation reveals that a key aspect of inflow transport approximation is applying accurate flux moments from a one-dimensional PN transport equation that considers both leakage and anisotropic scattering effects. This is analogous to assembly homogenization techniques [17]. However, two terms (multi-group data and fission source) are inconsistent with the theoretical model in the derivation of the previous inflow transport approximation.

When applying the flux shape with buckling $B$, the multigroup cross-section and scattering matrix in Eqs. (3) and (4) become:

This demonstrates that applying the flux shape with buckling $B$ eliminates the geometrical value $z$ from the derivation. Consequently, the previous one-dimensional PN transport equation becomes a homogenized system where cross-section and scattering matrix data are homogenized across all regions, including fuel, cladding, and moderator.

Beyond the homogenized system, the accurate fission source is also treated using homogenization techniques. Therefore, the transport equation in Eq. (11) is replaced by:

The solution for the flux moment then leads to:

Where

When $n$ is an even number and $n-1$ and $n+1$ are odd numbers.

For $n-1$:

For $n+1$:

Inserting Eqs. (30) and (31) into Eq. (27) leads to:

Where

If the order of $n$ is the maximum value, $\phi_{n+1}^g$ becomes 0. For odd $n$, Eq. (27) becomes:

Thus, the flux moment and transport cross-section are obtained using the improved inflow transport approximation. Compared with the previous inflow transport equation form, the improved version is based on homogenized cross-sections and accurate fission source, making it consistent with homogenization techniques.

2.3 Implementation of Improved Inflow Transport Approximation

In Choi's parametric study, the inflow transport approximation was found to be insensitive to buckling and Legendre polynomial order. Regarding buckling, even a ten-fold variation produced less than 2 pcm error in k-effective. Therefore, a typical buckling value ($B^2=0.0001$) was used for calculations. For Legendre polynomial order, the P1 transport equation is sufficient to calculate converged P0 transport cross-sections, with the same impact as P5 transport equation [9].

The improved inflow transport approximation employed the typical buckling value and P1 transport equation. The detailed iteration process is as follows: (a) Obtain homogenization data based on the outflow transport approximation for the actual problem. The DRAGON code produces homogenization data: $\Sigma_{x,mod,i}^{g,(0)}$, $\Sigma_{x,mod}^{g,(0)}$, $\phi_{n,mod,i}^{g,(0)}$, $\phi_{n,mod}^{g,(0)}$, $\Sigma_{s,n,mod,i}^{g,(0)}$ (n=1,2) where $i$ represents each region, $mod$ denotes the moderator region, $x$ represents the reaction type (f: fission, t: total, s: scattering), and $n$ is the Legendre polynomial order (anisotropic scattering effects for non-light nuclides are ignored). (b) Initialize flux moments and transport cross-sections. (c) Update P0 and P2 flux moments using Eq. (32) until convergence: $\phi_{n,mod}^{g,(k+1)}$ (n=1,2), $\Sigma_{tr,mod}^{g,(k+1)}$ (n=0,1,2) (n=0 and 2). (d) Update P1 flux moments. (e) Update P0 transport cross-sections. (f) Repeat steps (b)–(e) until flux moments and transport cross-sections converge.

In this procedure, flux moments and transport cross-sections may become negative. The iterative equation is:

Where $k$ is the iteration number.

This investigation focused only on the dominant moderator material (H2O). Therefore, the transport cross-section for H2O was selected for the improved transport approximation. A detailed discrepancy analysis between these transport approximations is presented in the next section.

3. Discrepancy Analysis

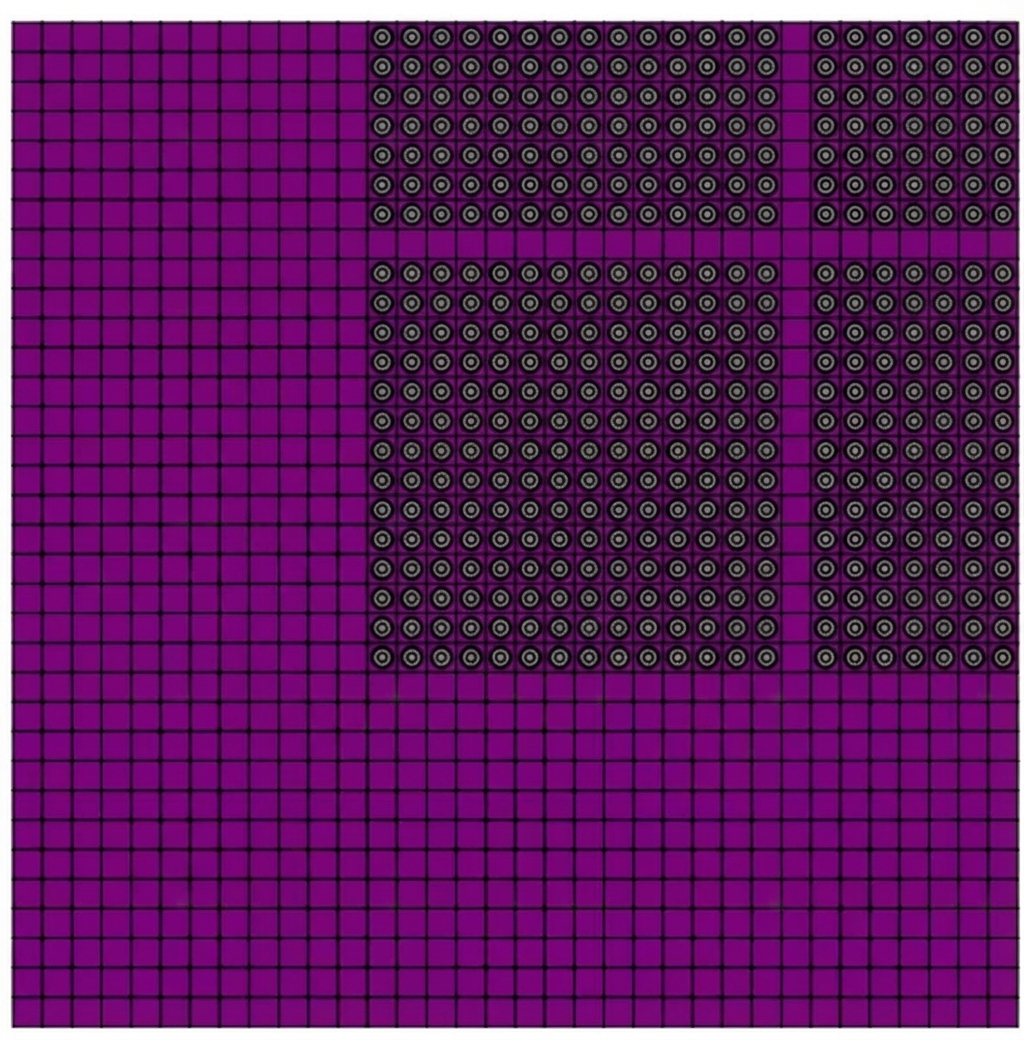

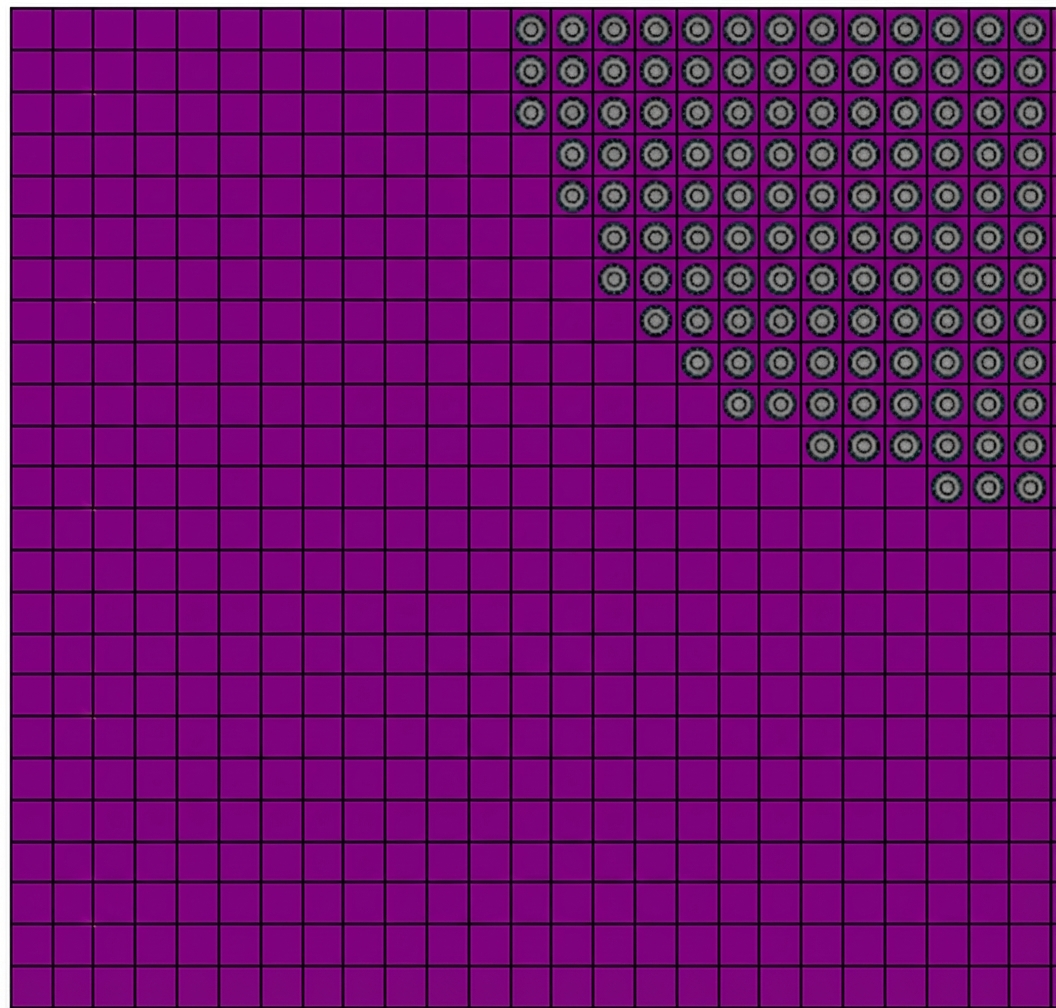

The typical LWR benchmark selected for this study to evaluate transport approximation accuracy is the Bettis Atomic Power Laboratory (BAPL-1) problem from the WIMS-D Library Update Project (WLUP) [18]. The geometry is shown in Fig. 1, and material compositions are listed in Table 1. The temperature was set to 300 K for all regions, and inter-gap spacing was omitted.

Fig. 1 The geometry of BAPL-1

Table 1 The material composition of BAPL-1

Material Nuclide Density (atom/barn·cm) Moderator 1H 6.6760×10⁻² 16O 3.3380×10⁻² Cladding Zr 4.8994×10⁻² 1H 3.1120×10⁻⁴ 16O 2.3127×10⁻² 10B 4.6946×10⁻²Figure 2a shows the transport cross-section for H2O using three transport approximations: outflow, previous inflow, and improved inflow. The outflow transport approximation exhibited large discrepancies in both thermal and fast energy ranges compared to the inflow approximations. The transport cross-section for H2O showed similar trends between the two inflow transport approximation methods.

To determine differences between these inflow transport approximations, P0 flux moment comparisons are shown in Figs. 2b and 2c. The main differences lie in the treatment of fission source and cross-sections. Reference results were obtained using the Monte Carlo code cosRMC, developed by Tsinghua University and the State Power Investment Corporation Research Institute (SPIC). Consequently, two types of P0 flux moment comparisons were performed.

1. Comparison in the moderator region:

(a) Normalized fission source + moderator cross-sections (previous method)

(b) Accurate fission source + moderator cross-sections

(Reference: cosRMC's P0 flux moment in the moderator region)

2. Comparison in the homogenized region:

(a) Normalized fission source + homogenized cross-sections

(b) Accurate fission source + homogenized cross-sections (improved method)

(Reference: cosRMC P0 flux moment in the homogenized region)

In Fig. 2b, the normalized P0 flux moment from the previous inflow transport approximation differs significantly from cosRMC results. For the moderator system, the P0 flux moment varies with different fission sources. When using the normalized fission source, the P0 flux moment becomes more distorted compared to using the accurate fission source. In Fig. 2c, the normalized P0 flux moment from the improved inflow transport approximation shows good agreement with cosRMC. For the homogenized system, the P0 flux moment also varies with fission source, exhibiting the same trend as the moderator system. Moreover, for the same fission source with different cross-sections, the homogenized cross-sections cause a 1 MeV decrease in the P0 flux moment, bringing it closer to the actual LWR system [19], whereas the moderator cross-section results differ. Therefore, the inflow transport approximation with accurate fission source and homogenized cross-sections improves P0 flux moment accuracy compared to the previous method.

4.1 General Description of Verification

The lattice code DRAGON5.0.5 was used for verification. Developed by École Polytechnique de Montréal for lattice calculations, it solves the neutron transport equation deterministically and can read various multi-group libraries, including WIMS-D and MATXS formats. This study employed the WIMS-D 70-group library [20] based on ENDF/B-VII.0 [21] to investigate anisotropic scattering effects. Different transport approximations were implemented in the WIMS-D 70 library through transport cross-sections and scattering matrices. Resonance self-shielding uses equivalence theory (SHI+LJ+LEVEL2) with the generalized Stamm'ler method [22], Livolant and Jeanpierre normalization factor, and Riemann integration [23]. The neutron transport calculation method was the interface current method (SYBILT). cosRMC served as the reference code, with k-infinity, k-effective, and P0 flux moments compared across various verification problems.

4.2 Typical LWR Fuel Cell and Fuel Assembly Cases

Typical LWR fuel cells and fuel assemblies were used to verify different transport approximations. Verification cases included fuel cell type, fuel assembly configuration, boron concentration, fuel enrichment, control rod material, and temperature in fuel assemblies with control rods.

The single fuel cell and 17×17 fuel assembly benchmarks were extracted from VERA problems 1A and 2A [24], featuring 3.1 wt% UO2 fuel, 0.743 g/cc moderators with 1,300 ppm boron concentration, and Zr-4 cladding. The temperature was 300 K for all regions. Geometric shapes for 1A and 2A are shown in Fig. 3, with detailed case descriptions provided in Table 2.

Fig. 3 Geometry shape of 1A (left) and 2A (right)

Table 2 Detailed description of each case

Case Description ²³⁵U w/o Temperature (K) Moderator (g/cm³) 1A fuel cell 3.1 300 0.743 2A fuel assembly 3.1 300 0.743 2H-typical fuel assembly+24 B4C 3.1 300 0.743 2H-0 ppm fuel assembly+24 B4C 3.1 300 0.743 (0 ppm B) 2H-4.8% fuel assembly+24 B4C 4.8 300 0.743 2G fuel assembly+24 AIC 3.1 300 0.743 2H-600 K fuel assembly+24 B4C 3.1 600 0.743Table 3 shows kinf results for each case with different transport approximations. Compared to cosRMC kinf values, DRAGON's inflow transport approximations yielded errors less than 100 pcm. Conversely, DRAGON's outflow transport approximation produced errors less than 100 pcm for fuel cells and fuel assemblies but approximately 150-250 pcm for fuel assemblies with control rods, consistent with previous research [9].

Compared to the previous inflow transport approximation, the improved method's results differed by less than 10 pcm for cases 1A and 2A. The improved transport approximation underestimated results by 11-49 pcm for 2H-typical, 2H-0 ppm, 2H-4.8%, and 2G cases, and overestimated by 46 pcm for 2H-600 K. This indicates that transport approximations have minimal influence on fuel cells and fuel assemblies but affect fuel assemblies with control rods. For 300 K cases, the improved transport approximation's homogenization techniques, based on homogenized cross-sections and accurate fission source, account for resonance self-shielding effects in fuel materials. Compared to the previous inflow transport approximation, the improved method absorbs more neutrons across different cases, decreasing kinf results. For the 600 K case, weakened resonance self-shielding effects in the improved inflow transport approximation with increasing temperature [25] led to increased kinf compared to the previous transport approximation.

Table 3 Results of kinf in different cases

Case cosRMC (±pcm) DRAGON Method1* DRAGON Method2† DRAGON Method3‡ 1A ±30 -80 -83 -78 2A ±30 13 14 16 2H-typical ±31 127 -22 -51 2H-0 ppm ±32 247 72 46 2H-4.8% ±31 213 54 5 2G ±29 152 1 -10 2H-600 K ±27 233 -3 43*Method1: outflow transport approximation

†Method2: previous inflow transport approximation

‡Method3: improved inflow transport approximation

Consequently, different inflow transport approximations achieved higher accuracy than the outflow transport approximation in reactivity calculations, with kinf errors less than 50 pcm.

Figures 4 and 5 compare normalized P0 flux moments across these cases. Compared to cosRMC results, the improved inflow transport approximation showed better agreement than the previous method. The previous inflow transport approximation slightly overestimated the P0 flux moment by approximately 1 MeV and underestimated it in the thermal energy range, making the spectrum harder than the improved method.

Additionally, the improved inflow transport approximation results across different LWR cases showed good agreement with cosRMC, demonstrating greater versatility than the previous method. It achieved higher accuracy for fuel cells, fuel assemblies, varying boron concentrations, fuel enrichment levels, control rod materials, and temperatures in fuel assemblies with control rods. Therefore, the improved inflow transport approximation is accurate, universal, and suitable for LWR analysis.

4.3 Analysis of Influence Factors

Previous investigations indicated that inflow transport approximation was problem-dependent. However, transport approximations are problem-independent data in most nuclear data libraries. Therefore, studying the influence of transport approximation is necessary to produce a general nuclear data library.

Figure 6 shows the macroscopic transport cross-section and relative error for H2O in case 2A using different inflow transport approximations. The macroscopic transport cross-section for H2O was similar across most LWR cases, with the largest differences appearing in the thermal energy group for the 600 K case. The relative error of transport cross-section in the 600 K case was approximately 30-40% in case 2A across different inflow transport methods, but less than 20% in other cases. Thus, temperature is the most significant factor influencing inflow transport approximations, as determined through transport cross-section comparison.

For the previous inflow transport approximation, the transport cross-section was based on the moderator region, with relative error to case 2A less than 1% using the same moderator cross-sections. Therefore, the previous method was only related to the moderator region. For the improved inflow transport approximation, the transport cross-section was based on the homogeneous system, with relative error to case 2A exceeding 5% in the 0.28 eV to 27.7 eV range. In a homogeneous system, the resonance self-shielding effect for fuel and absorber nuclides was considered in transport cross-section derivation. The neutron spectrum changed according to different nuclide density ratios in fuel and absorber materials, making the improved inflow transport approximation differ from the previous method and consistent with actual LWR models.

The transport cross-section showed strong temperature correlation but minimal variation across different LWR operational factors such as fuel assembly type, boron concentration, fuel enrichment, and control rod materials in fuel assemblies with control rods. Two different WIMS-D 70-group libraries based on the improved inflow transport approximation were created to test influencing factors. The first is problem-dependent, where transport cross-section and scattering matrix data for ¹H and ¹⁶O are case-specific, developed using the improved inflow method for actual cases. The second is problem-independent, where transport cross-section and scattering matrix data for H-1 and O-16 are general, developed using the improved inflow method from the typical 2H case (B4C, 300 K, 1,300 ppm, and 3.1 wt%).

Table 4 shows kinf results using the improved transport approximation. Comparing problem-dependent and problem-independent libraries, kinf error was less than 20 pcm for most cases, except 37 pcm for the 2H case at 600 K. This indicates that including fuel and absorber nuclides in the inflow transport approximation has minimal influence on kinf calculations, but temperature affects the results, consistent with transport cross-section differences shown in Fig. 6. Although the largest transport cross-section differences occurred in the resonance energy range, the magnitude was comparatively smaller than in the thermal range, and its influence on kinf error was less than 20 pcm per case. Therefore, the improved inflow transport approximation depends only on temperature and can be easily implemented in temperature-dependent nuclear data libraries.

Table 4 Results of kinf in improved inflow transport approximation

Case DRAGON5.0.5 Dependent DRAGON5.0.5 Independent cosRMC (±pcm) 2H(typical) -51 -51 ±31 2H(0 ppm) -78 -76 ±30 2H(4.8 wt%) 16 17 ±30 2G(AIC) 46 40 ±32 2H(600K) -10 -12 ±31 43 6 ±274.4 Application of Inflow Transport Approximation to Core Cases

The Babcock & Wilcox (B&W) critical experiment benchmarks [26] were selected to verify different transport approximations in core cases. The B&W 1484 core 1 and core 3 cases were chosen, with geometries shown in Fig. 7. B&W 1484 core 1 is a 48×48 configuration, and core 3 is a 68×68 configuration.

Fig. 7 Geometry shape of B&W 1484 Core 1 (left) and Core 3 (right)

Table 5 shows results for B&W 1484 core 1 and core 3 cases (2D and 3D). The outflow transport approximation introduced errors exceeding 1,000 pcm, while both inflow transport methods yielded results close to reference values. For B&W 1484 core 1 (2D and 3D), the improved inflow transport approximation overestimated kinf by approximately 364 pcm and 291 pcm, respectively. For B&W 1484 core 3 (2D and 3D), it overestimated kinf by approximately 115 pcm and 121 pcm, respectively. The kinf error in B&W 1484 core 1 and core 3 cases was inversely proportional to LWR assembly cases. Additionally, different transport approximations were sensitive to small core configurations, causing over 1,000 pcm errors in kinf calculations for core 1 and approximately 600 pcm for core 3.

Although the previous inflow method produced results close to reference values, the improved inflow method better represents the actual system and is consistent with theoretical models. This tendency may stem from limitations in the WIMS-D library, such as neglecting scattering resonance integrals and using lumped fission spectra.

In summary, the outflow transport approximation can introduce errors exceeding 1,000 pcm in B&W 1484 core 1 and core 3 cases, while inflow transport methods remain relatively accurate for core calculations.

Table 5 Results of kinf/keff in B&W 1484 Core 1 and Core 3

Case CosRMC/Experiment (±pcm) DRAGON Method1* DRAGON Method2† DRAGON Method3‡ Core 1(2D) ±30 1581 -72 292 Core 1(3D) ±30 1367 -235 56 Core 3(2D) ±30 1170 553 668 Core 3(3D) ±30 1331 725 846*Method1: outflow transport approximation

†Method2: previous inflow transport approximation

‡Method3: improved inflow transport approximation

5. Conclusion

This study evaluated the improvement and application of inflow transport approximation in LWR analysis by comparing P0 flux moments, keff, and kinf against reference results. The improved inflow transport approximation differs from the previous method by employing homogenized cross-sections and accurate fission source.

For LWR assembly cases, three transport approximations (outflow, previous inflow, and improved inflow) were compared across fuel cells, fuel assemblies, and variations in boron concentration, fuel enrichment, control rod materials, and temperature in fuel assemblies with control rods. The inflow transport approximation kinf error was less than 100 pcm compared to the Monte Carlo code cosRMC, demonstrating greater accuracy than the outflow transport approximation in treating anisotropic scattering effects. For P0 flux moments, the improved inflow transport approximation results were closer to cosRMC in all cases, with homogenized cross-sections and accurate fission source being the primary influencing factors. Additionally, the improved inflow transport approximation depends only on temperature for typical LWR cases. Excluding temperature effects, kinf error was less than 20 pcm between problem-dependent and problem-independent transport approximations.

For B&W 1484 core cases, the outflow transport approximation introduced errors exceeding 1,000 pcm, while inflow transport approximations significantly improved kinf accuracy, yielding results closer to reference values.

In summary, the improved inflow transport approximation provides more flexible and accurate treatment of anisotropic scattering effects and can be easily implemented in temperature-dependent nuclear data libraries for LWR analysis.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Xiang Xiao, Kan Wang, Tong-Rui Yang, and Yi-Xue Chen. The first draft was written by Xiang Xiao, and all authors commented on previous versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0307800-05).

References

-

J. Rhodes, K. Smith, D. Lee, CASMO-5 development and applications. Paper presented at the Proceedings of PHYSOR 2006 ANS Topical Meeting, (Vancouver, Canada, 2006)

-

A. Yamamoto, Y. Kitamura, Y. Yamane, Simplified treatments of anisotropic scattering in LWR core calculations. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 45(3), 217–229 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/18811248.2008.9711430

-

K. S. Kim, M. L. Williams, D. Wiarda et al., Development of a new 47-group library for the CASL neutronics simulators. Paper presented at the Mathematics and Computations, Supercomputing in Nuclear Applications and Monte Carlo International Conference, (Nashville, America, 2015)

-

B. Kochunas, B. Collins, D. Jabaay, et al., Overview of development and design of MPACT: Michigan parallel characteristics transport code. Paper presented at the International Conference on Mathematics and Computational Methods Applied to Nuclear Science and Engineering, (San Francisco, America, 2013)

-

N.A. Gibson, Novel Resonance Self-Shielding Methods for Nuclear Reactor Analysis. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2016). http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/103658

-

W. Boyd, N. Gibson, B. Forget et al., An analysis of condensation errors in multi-group cross section generation for fine-mesh neutron transport calculations. Ann. Nucl. Energy 112, 267–276 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2017.09.052

-

L.X. Liu, C. Hao, Y.L. Xu, Equivalent low-order angular flux nonlinear finite difference equation of MOC transport calculation. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 125 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00834-2

-

B.R. Herman, B. Forget, K. Smith et al., Improved diffusion coefficients generated from Monte Carlo codes. Paper presented at the International Conference on Mathematics and Computational Methods Applied to Nuclear Science and Engineering, (San Francisco, America, 2013)

-

G. Bell, G. Hansen, H. Sandmeier, Multitable Treatments of Anisotropic Scattering in SN Multigroup Transport Calculations. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 28(3), 376–383 (1967). https://doi.org/10.13182/nse67-2

-

S. Choi, K. Smith, H. C. Lee, et al., Impact of inflow transport approximation on light water reactor analysis. J. Comput. Phys. 352, 373 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2015.07.005

-

Z.X. Fang, M. Yu, Y.G. Huang, et al., Theoretical analysis of long-lived radioactive waste in pressurized water reactor. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 72 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00866-0

-

M. Dai, M.S. Cheng, Application of material-mesh algebraic collapsing acceleration technique in method of characteristics–based neutron transport code. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 87 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00923-w

-

G.C. Zhang, J. Liu, L.Z. Cao, et al., Neutronic calculations of the China dual-functional lithium–lead test blanket module with the parallel discrete ordinates code Hydra. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 74 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00789-4

-

R. Roy, G. Marleau, A. Hebert, User guide for dragon version 5: Technical Report IGE 335. (École Polytechnique de Montréal, Canada, 2014)

-

K. Wang, Z. G. Li, D. She, et al., RMC - A Monte Carlo code for reactor core analysis. Ann. Nucl. Energy 82, 121–129 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2014.08.048

-

R. E. MacFarlane and D. W. Muir, The NJOY Nuclear Data Processing System, LA-12740-M. (Los Alamos National Laboratory, America, 1999)

-

[Reference missing in original]

-

D. L. Aldama, F. Leszczynski, and A. Trkov, WIMS-D Library Update. Paper presented at the IAEA Research Project Coordination Meeting, (Austria, 2003). http://www.pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/te_1468_web.pdf#page=22

-

K. S. Kim, M. L. Williams, D. Wiarda, et al., Development of the multigroup cross section library for the CASL neutronics simulator MPACT: Method and procedure. Ann. Nucl. Energy 133, 46–58 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2019.05.010

-

M. Edenius, K. Ekberg, B. H. Forssén, et al., CASMO-4, A Fuel Assembly Burnup Program, User's Manual. (Studsvik Am. Inc, 1995)

-

M. B. Chadwick, P. Obložinský, M. Herman, et al., ENDF/B-VII.0: Next Generation Evaluated Nuclear Data Library for Nuclear Science and Technology. Nucl. Data Sheets 107(12), 2931–3060 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2006.11.001

-

A. Hebert, G. Marleau, Generalization of the Stamm'ler method for the self-shielding of resonant isotopes in arbitrary geometries. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 108(3), 230–239 (1991). https://doi.org/10.13182/NSE90-57

-

A. Hébert, Revisiting the Stamm'ler self-shielding method. Paper presented at the 25th CNS Annual Conference, (Toronto, Canada, 2004)

-

A. T. Godfrey, VERA core physics benchmark progression problem specifications. (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, America, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12168

-

D. Lee, K. Smith, J. Rhodes, The impact of ²³⁸U resonance elastic scattering approximations on thermal reactor Doppler reactivity. Paper presented at the Int. Conf. Phys. React. 2008, PHYSOR 2008, (Interlaken, Switzerland, 2008)

-

G.S. Hoovler, M.N. Baldwin, R.L. Eng et al., Critical Experiments Supporting Close Proximity Water Storage of Power Reactor Fuel. Nucl. Technol. 51(2), 217–237 (1980). https://doi.org/10.13182/nt80-a32604